A new report lays bare the impact of chronic pain in young people. During Kids in Pain Week (22–28 September), an expert shares practical steps for pharmacists to improve care.

Sydney-based Laura was just 10 years old when a bout of shingles left her with constant, debilitating pain. Laura went from being a fit and active middle sister to being unable to walk or move without a wheelchair at the age of 11, and completely reliant on her family for care. Doctors were stumped and investigations proved fruitless.

‘I was so sick of doctors – waiting for the doctors and waiting to do anything and just so ready to give up,’ Laura said.

When living with chronic pain, it’s easy to feel misunderstood and lonely, she shared.

‘Laura was having a really hard time, was depressed, barely talking and struggling. It was so hard to see her like that,’ Laura’s mum, Michelle said.

‘People underestimate how chronic pain may start as a physical issue but then becomes a mental health issue when everything is so uncertain and you aren’t sure if life will ever be what it was.’

Around one in five children aged 6–18 live with chronic pain, which equates to approximately 877,000 Australian kids – according to Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) data.

The inaugural Kids in Pain Report from Chronic Pain Australia shows how pain affects every aspect of these children’s lives, as well as their families, and the many who are likely unaccounted for, said pharmacist and Chronic Pain Australia chairperson, Nicolette Ellis MPS.

‘In 2019 the World Health Organization recommended that chronic pain be recognised as a condition in its own right and provided a way to capture that in healthcare data with ICD-11 coding,’ she said. ‘But chronic pain isn’t recognised as a condition in Australia; it’s recognised only as a symptom of an injury or another condition.’

Without robust prevalence data, chronic pain will remain missing from national policy – including the Medicare Benefits Schedule and the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, Ms Ellis warned.

‘That cascades down into service planning and investment, which is not currently matched to need,’ she said. ‘For example, Australia only has nine specialist paediatric pain clinics; Tasmania and the Northern Territory have none, so families often travel 4–6 hours for specialist appointments.’

What does chronic pain look like in children?

Most (71%) of children experience musculoskeletal pain, typically due to rheumatoid arthritis and autoimmune conditions as well as lower-back pain, knee pain and other joint pain. Migraine and headaches, abdominal pain, connective-tissue disorders, neuropathic pain and pelvic pain are also prominent.

‘Most children have overlapping conditions – for example, migraine with abdominal pain, or musculoskeletal and neuropathic pain – so it’s rarely a single tidy diagnosis,’ Ms Ellis said.

There is a high correlation between neurodivergence and pain, with almost three-quarters (72.9%) of children with chronic pain having at least one neurodivergent diagnosis.

‘Life can be more stressful for neurodivergent individuals, producing hormones that amplify pain signals,’ she said.

About 60% of children with chronic pain also identified as female.

‘Women and girls have denser nerve networks and different immune systems,’ Ms Ellis said. ‘Fluctuations in oestrogen can also increase pain signals, while testosterone tends to reduce them.’

Why is there such a long road to diagnosis?

For over 64% of children living with chronic pain, it took at least 3 years to receive a diagnosis.

‘Culturally, there’s a belief that persistent pain is an “older person’s condition”,’ Ms Ellis said. ‘So many children’s pain is dismissed.’

It’s often assumed there is another reason driving the symptoms.

‘Common explanations given to families are anxiety, a mental-health issue, “growing pains” that will resolve, or school avoidance,’ she said. ‘That invalidates the child and parent, and delays diagnosis.’

Children can face significant challenges navigating the healthcare system, getting answers, and accessing quality treatment, leading to cascading consequences.

‘Around 80% of children have a secondary mental health challenge, report sleep issues and forgo sport and similar activities,’ she said. ‘Over 80% miss school, about 1 day per week on average, with many finding the school system inflexible and invalidating, with pain dismissed or labelled as avoidance.’

Should a child experience ongoing, persistent pain, it should be taken ‘very seriously’ by health professionals – including pharmacists – with early intervention and thorough assessment ideally taking place within the first 3–6 months.

‘Early action reduces chronicity, helps build tools and confidence in self-management, and helps keep children in school and engaged socially,’ Ms Ellis said.

What’s the pharmacist’s role?

Parents reported that they often see their pharmacist first to discuss their child’s pain condition. To expedite diagnosis and ensure appropriate care, Chronic Pain Australia has released a Pharmacist Guide which includes language tips for discussing pain with children, ways to explain pain, and what good pain management looks like.

‘Pharmacists should ask how long the pain has been present and validate that it’s challenging to live with,’ Ms Ellis said. ‘Emphasise the importance of seeing a local GP for assessment and early diagnosis.’

Other key language tips include using ‘lives with pain’ over ‘suffers from’. Pharmacists should also describe ‘bad” or ‘challenging’ days rather than ‘flare-ups’.

‘Link with local providers, such as occupational therapists, physiotherapists and psychologists – who understand different communication and treatment needs, including for neurodivergent children who may express pain differently,’ she said.

When addressing children with neurodivergence, pharmacists should inquire how best to communicate with them, what topics to avoid and what information would help.

‘Communication should always be age-appropriate and family-centred,’ Ms Ellis said. ‘The goal is to create a friendly, approachable environment where children feel comfortable sharing, while parents can help fill in the picture when needed.’

How should symptom management be approached?

Management approaches for chronic pain depend on the child, condition, and whether function improves, Ms Ellis said.

‘In paediatric pain medicine we try to avoid medicines and use them sparingly, but if a non-functional child becomes functional on a medicine that may restore quality of life – that should be central to pain management.’

Ms Ellis recalls an example of a 14-year-old girl prescribed an opioid to be taken before menstruation for 4–5 days. While some healthcare professionals were quick to label this approach an addiction risk, it perhaps kept her in school during severe periods while investigations took place for endometriosis or polycystic ovarian syndrome.

‘Pharmacists concerned about higher-risk medicines should focus conversations on functional benefit, asking “Is this improving your ability to do things?”’ she said. ‘If not, initiate a discussion about whether to continue therapy, given the potential harms.’

With her mum’s support and extensive physical therapies, Laura was able to walk into her first day of high school without a walking stick. While she has good and bad days and constant flare ups, there are wins along the way – such as being able to start carrying a backpack rather than relying on a roller case.

‘It’s an invisible disability with constant pain that isn’t linear – there are different levels and sensations all the time and that changes the way I approach daily life,’ Laura said.

‘[But] when mum said I will keep fighting for you – it was almost like a promise, and she’s always kept it.’

Ruth Nona[/caption]

Ruth Nona[/caption]

Kate Gunthorpe MPS[/caption]

Kate Gunthorpe MPS[/caption]

Madison Low[/caption]

Madison Low[/caption]

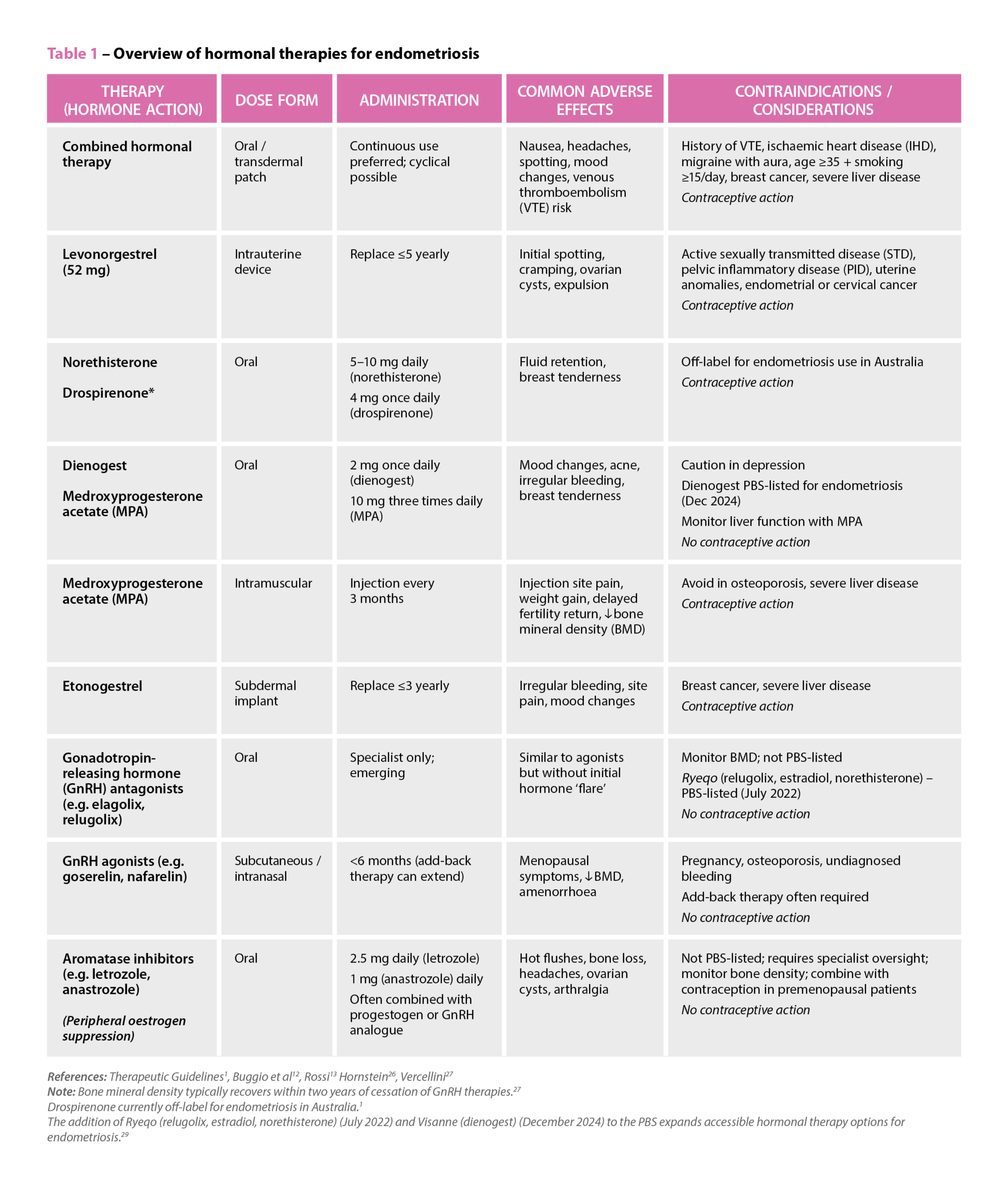

References: Therapeutic Guidelines

References: Therapeutic Guidelines

Genevieve Adamo MPS (Image: Steve Christo Photography)[/caption]

Genevieve Adamo MPS (Image: Steve Christo Photography)[/caption]