On 1 June 2021, 46-year-old Victorian man Bradley Scott Liefvoort was found dead in his apartment from an overdose of tapentadol and oxycodone, holding onto the pack of the prescription medicines that contributed to his death.

Toxicological analysis of post-mortem samples identified the presence of the following in his blood:

- ethanol 0.05 g/100mL

- oxycodone ~0.5 mg/L

- tapentadol ~2.2 mg/L

- diazepam ~0.1 mg/L and its metabolite nordiazepam

- mirtazapine ~0.02 mg/L.

Mr Liefvoort, a father of triplets who was separated from his wife when he died, was prescribed these medicines for a rare autoimmune disorder, granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

Although his prescription medicine dependence emerged more than a decade before his death, doctor shopping to feed an unrecognised substance-use disorder led to the prescribing of 988 tapentadol, 1,785 oxycodone and 556 diazepam tablets within the 6 months leading up to his death.

Coroner Audrey Jamieson found that nine GPs failed to uphold their legal obligation by checking the state’s Real Time Prescription Monitoring (RTPM) system, SafeScript, on 71 occasions during that 6-month period.

‘The conduct of Bradley Scott Liefvoort’s treating medical practitioners who collectively prescribed opioid and other drugs in excess of his medical need contributed to the chain of events leading to his death,’ the coroner stated in her finding.

‘At the time of Bradley’s death, SafeScript had already been compulsory to use for more than a year when prescribing or dispensing either of the two drugs that contributed centrally to the death: oxycodone and tapentadol.’

Victoria Police, who found Mr Liefvoort at his home, catalogued the following medicines:

- 1 empty bottle of 1 mg prednisolone

- 1 packet of Palexia SR 100 mg (a brand of tapentadol) with 3 tablets missing

- 4 sealed boxes of oxycodone (Endone 80 tablets)

- 1 empty bottle of prednisolone 25 mg tablets

- paracetamol (Panamax)

- mirtazapine

- methotrexate (Methoblastin)

- pizotifen (Sandomigran )

- pantoprazole (Somac)

- folic acid (Megafol)

- diazepam (Valium).

Professional conduct investigations

Several doctors involved in the case are also under investigation by the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA).

But the 14 different pharmacies he visited from 1 October 2020 to 1 January 2021, among others, could also have been included in the investigation by the coroner, said PSA Victorian State Manager and Digital Health Lead Jarrod McMaugh.

Next time a person dies after accessing unsafe prescription medicine, there’s ‘every reason to believe the coroner will focus on pharmacists’.

‘If those pharmacists were shown to have unprofessional actions, they would also be referred to AHPRA,’ said Mr McMaugh.

Helpful resources for pharmacists around their professional obligations and helping patients through substance misuse include:

|

‘Pharmacists should always maintain a primary concern for the safety of their patients, which often overlaps with concern for your own future professional role, [should] you lose the ability to practice.

Checking patient histories

At the start of Mr Liefvoort’s misuse, an orange alert may have been issued in SafeScript, indicating supply of the medicines was picked up earlier than expected.

‘But after a period of time, it would be very clear the total supply was escalating, and this would change to red alert,’ said Mr McMaugh.

The first responsibility pharmacists have is to check patients’ RTPM profiles to determine whether alerts, designed as warnings for health practitioners to consider, are relevant.

‘Some medicines have doses high enough to trigger alerts, for example, opioids prescribed at a dose higher than 100 milligrammes morphine equivalent per day,’ he said.

‘Fentanyl patches, for example, will always trigger a red alert, but if you’re satisfied it’s consistent with their treatment plan, it’s perfectly normal to supply.’

If you’re not satisfied it’s safe to supply a medicine, Mr Maugh recommends taking the patient aside and respectfully asking:

- how are you using the medicine?

- are you getting the pain relief you’re expecting?

- is there something else going on for you?

Should you identify signs of substance misuse, Mr McMaugh suggests advising the patient that you need to speak with all the prescribing GPs in their SafeScript profile. Next steps include:

- recommending prescribers start utilising RTPM appropriately

- advising prescribers that the patient needs a referral to a specialist for management of a substance-use disorder

- referring the patient back to one GP to act as the ongoing management coordinator for their care.

Standing firm to effect change

While there are chances both the GP and patient may resist this approach, Mr McMaugh said it’s important not to undermine your decision by continuing to supply the medicine.

He suggests informing the patient that dispensing the medicines would be unsafe and they would be better served discussing opioid substitution treatment options with their doctor.

‘They don’t have to take your advice, but ensure your records, including in SafeScript, [are updated] so the next practitioner could consider that recommendation as part of their overall approach,’ said Mr McMaugh.

In most jurisdictions, the prescription must be returned to the patient. But it’s important to annotate the script to reflect that the patient presented at your pharmacy at a certain date and that the medicine was not supplied.

This might ensure the next pharmacist who receives the prescription checks the patient’s RTPM profile, notes the history associated with substance use disorder, and similarly decides not to supply, while reinforcing the referral pathway.

‘When every health practitioner provides the patient with a referral to a substance use disorder specialist, they might decide, “this is the only path forward for me to keep the symptoms of the substance use disorder under control”,’ said Mr McMaugh.

‘We’re increasingly seeing incidents where alert fatigue has been identified as a contributing factor. It’s not that there wasn’t an alert in place, but that it was lost among the other alerts the clinician saw,’ Prof Baysari says.

‘We’re increasingly seeing incidents where alert fatigue has been identified as a contributing factor. It’s not that there wasn’t an alert in place, but that it was lost among the other alerts the clinician saw,’ Prof Baysari says.

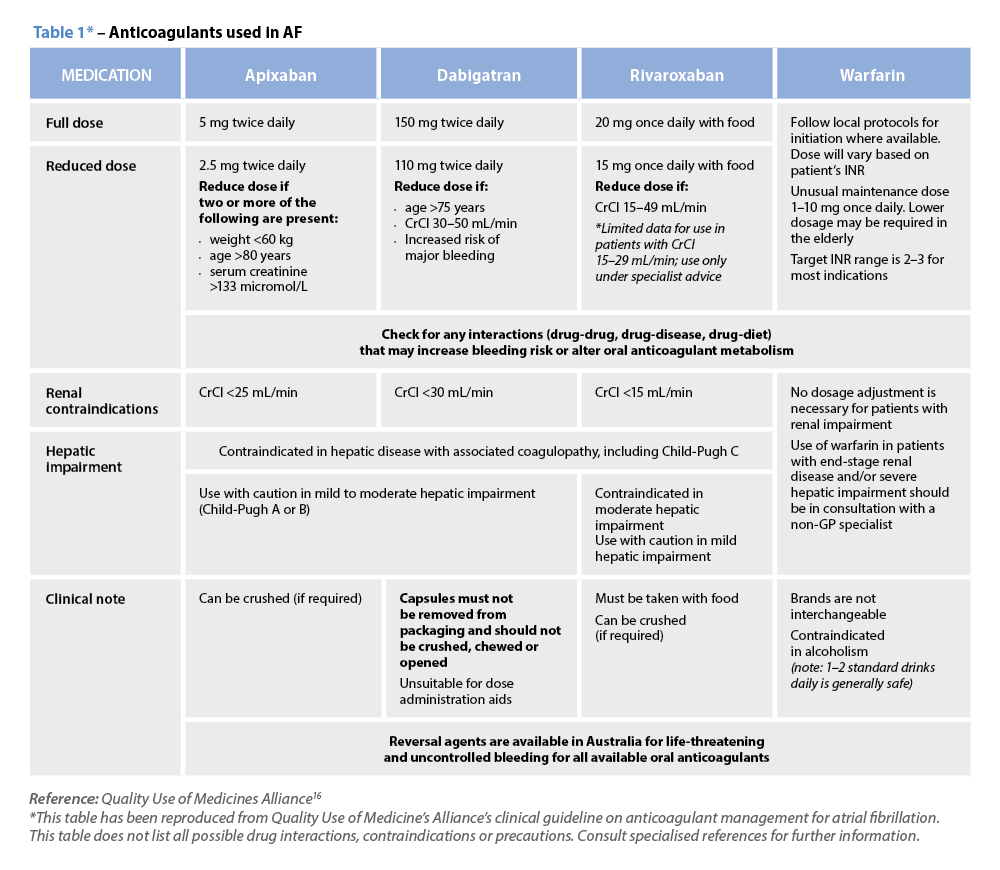

Beyond the arrhythmia, AF often signals broader pathological processes that impair cardiac function and reduce quality of life and life expectancy.5 Many of these conditions are closely linked to social determinants of health, disproportionately affecting populations with socioeconomic disadvantage. Effective AF management requires addressing both the arrhythmia and its underlying contributors.4

Beyond the arrhythmia, AF often signals broader pathological processes that impair cardiac function and reduce quality of life and life expectancy.5 Many of these conditions are closely linked to social determinants of health, disproportionately affecting populations with socioeconomic disadvantage. Effective AF management requires addressing both the arrhythmia and its underlying contributors.4  C – Comorbidity and risk factor management

C – Comorbidity and risk factor management Warfarin

Warfarin