Ever since our ancestors came down from the trees, we’ve been struggling to evict parasitic worms.

They are pesky, numerous and known as helminths. Data from the Human Genome Project (1990–2003) and modern archaeology reveal that we humans have lived with these parasitic worms for about 150,000 years. Altogether, we’ve inherited roughly 300 species, including ‘heirloom’ helminths from our African ancestors and ‘souvenir’ helminths from our animal contacts.1,2,3,7

This long association exists because the eggs and larvae of many helminths thrive in warm, moist soil or fresh water. All are easily spread via accidental ingestion, skin penetration, bites from affected organisms – so-called ‘vectors’ – or consumption of a vector as food.

Transmission is also highly dependent on climate, hygiene and vector exposure.3,4,8 The World Health Organization estimates that 1.5 billion people – roughly 24% of the world’s population – are infected with soil-transmitted helminths alone.7 This is probably an underestimate, as the infection burden falls on low-income developing countries with poor quality data and underreporting.3

What they do

Our helminthic fellow travellers come in three categories: trematodes, also known as flukes; cestodes, or tapeworms; and nematodes, or roundworms.4,5 Depending on their size and activity, helminths damage numerous tissues as they move through the body – commonly affecting skin, lungs, liver and intestines.4,11 Resulting diseases include schistosomiasis, echinococcosis and trichinosis. Helminths may also worsen symptoms of serious infectious diseases, including tuberculous, malaria and HIV/ AIDS.3,4 Many infections are long-lived but asymptomatic. Others are often symptomatic, such as Australia’s most common worm infection – threadworms.12 At night, threadworms lay eggs between the buttocks, which can cause extreme itching, redness and scratches.12

Past efforts

While early humans undoubtedly fought helminths, written records begin with the Ebers Papyrus, from about 1550 BCE. It confirms Egyptians used herbs and bitter- tasting, purgative plants like wormwood and tansy as remedies. The Greeks, including Hippocrates (c. 460–375 BCE), treated helminths with garlic, fennel and anise. Roman and Arabic physicians also treated and described worms.7,9

Excavations of medieval latrines reveal helminths did not respect class. Richard III (1452–85) was infected with roundworms. He was likely treated with wormwood, as recommended by Gilbert the Englishman (1180–1250).9

By the 17th century, helminth science had emerged, as evidenced by the fact that Carl Linnaeus (1707–78) describe and named six helminths. Still, the use of traditional treatments like arsenic, salt and turpentine oil continued until the early 20th century. It wasn’t until the 1950s that the first safe anthelmintics like piperazine appeared.3,7,10

Today

Like the types of helminths they treat, there are many ‘anthelmintic’ remedies. Also, like helminths, they are divided into categories: vermicides kill worms, and vermifuges help expel them without harming their hosts.4,6,13 Anthelmintics are further grouped depending on their target parasite and mechanism of action.

Old-fashioned piperazine, a vermifuge, fights nematode infections by paralysing the invader. Praziquantel paralyses trematodes and cestodes, and mebendazole kills nematodes by inhibiting the uptake of nutrients.4,13

Luckily, unlike our African ancestors, we in Australia have access to a selection of anthelmintics to treat these infections.14,15

Online References: Anthelmintic Agents

- National Institutes of Health. National Human Genome Research Institute. The human genome project. 2022.

- Tishkoff SA, Pakstis AJ, Stoneking M, et al. Short tandem-repeat polymorphism/alu haplotype variation at the PLAT locus: implications for modern human origins. Am J Hum Genet 2000;67(4):901–25.

- Jayawardene KLTD, Palombo EA, Boag PR. Natural products are a promising source for anthelmintic drug discovery. Biomolecules 2021;11(10):1457.

- Campbell S; Soman-Faulkner K. Antiparasitic drugs. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing 2022.

- Holden-Dye L, Walker RJ. Anthelmintic drugs and nematicides: studies in Caenorhabditis elegans. WormBook: The Online Review of C. elegans Biology [Internet]. Pasadena (CA) 2005–2018.

- Abongwa M, Martin RJ, Robertson AP. A brief review on the mode of action of antinematodal drugs. Acta Vet (Beogr) 2017;67(2):137–152.

- Cox FE. History of human parasitology. Clin Microbiol Rev 2002;15(4):595–612. Erratum in Clin Microbiol Rev 2003;16(1):174.

- WHO Expert Committee. Prevention and control of schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 2002;912.

- Harvey K. Parasites and pests from the medieval to the modern. Welcome Collection. 20 March 2019.

- Horton J. Global anthelmintic chemotherapy programs: learning from history.

Trends Parasitol 2003;19(9):405–9. - Wakelin D. Helminths: pathogenesis and defenses. In Medical Microbiology 4th edition. Baron S (Ed.) Galveston (TX): University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston 1996. Chapter 87.

- HealthDirect. Worms in humans. 2021.

- Partridge FA, Forman R, Bataille CJR, et al. Anthelmintic drug discovery: target identification, screening methods and the role of open science. Beilstein J Org Chem 2020;(16):1203–1224.

- Department of Health and Aged Care. Therapeutic Goods Administration. Public Summary. BILTRICIDE Praziquantel 600mg tablet bottle.

- Department of Health and Aged Care. Therapeutic Goods Administration. Public Summary. COMBANTRIN-1 mebendazole 100mg tablet blister pack.

‘We’re increasingly seeing incidents where alert fatigue has been identified as a contributing factor. It’s not that there wasn’t an alert in place, but that it was lost among the other alerts the clinician saw,’ Prof Baysari says.

‘We’re increasingly seeing incidents where alert fatigue has been identified as a contributing factor. It’s not that there wasn’t an alert in place, but that it was lost among the other alerts the clinician saw,’ Prof Baysari says.

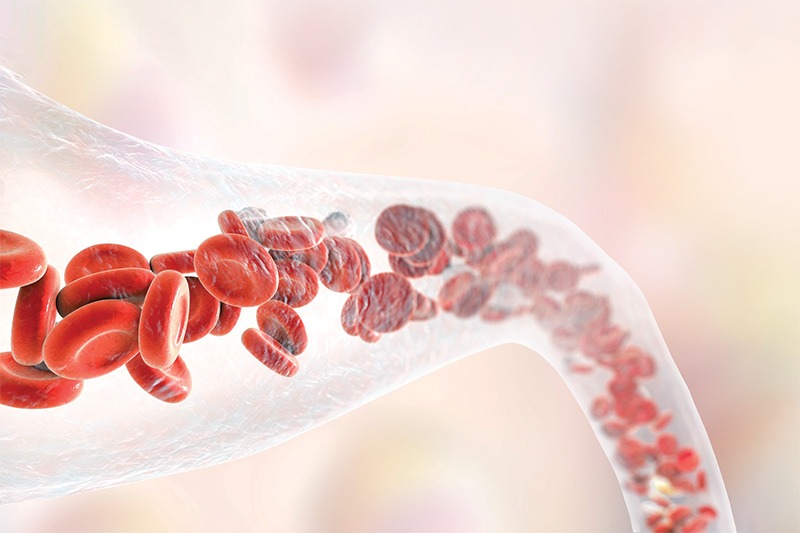

Beyond the arrhythmia, AF often signals broader pathological processes that impair cardiac function and reduce quality of life and life expectancy.5 Many of these conditions are closely linked to social determinants of health, disproportionately affecting populations with socioeconomic disadvantage. Effective AF management requires addressing both the arrhythmia and its underlying contributors.4

Beyond the arrhythmia, AF often signals broader pathological processes that impair cardiac function and reduce quality of life and life expectancy.5 Many of these conditions are closely linked to social determinants of health, disproportionately affecting populations with socioeconomic disadvantage. Effective AF management requires addressing both the arrhythmia and its underlying contributors.4  C – Comorbidity and risk factor management

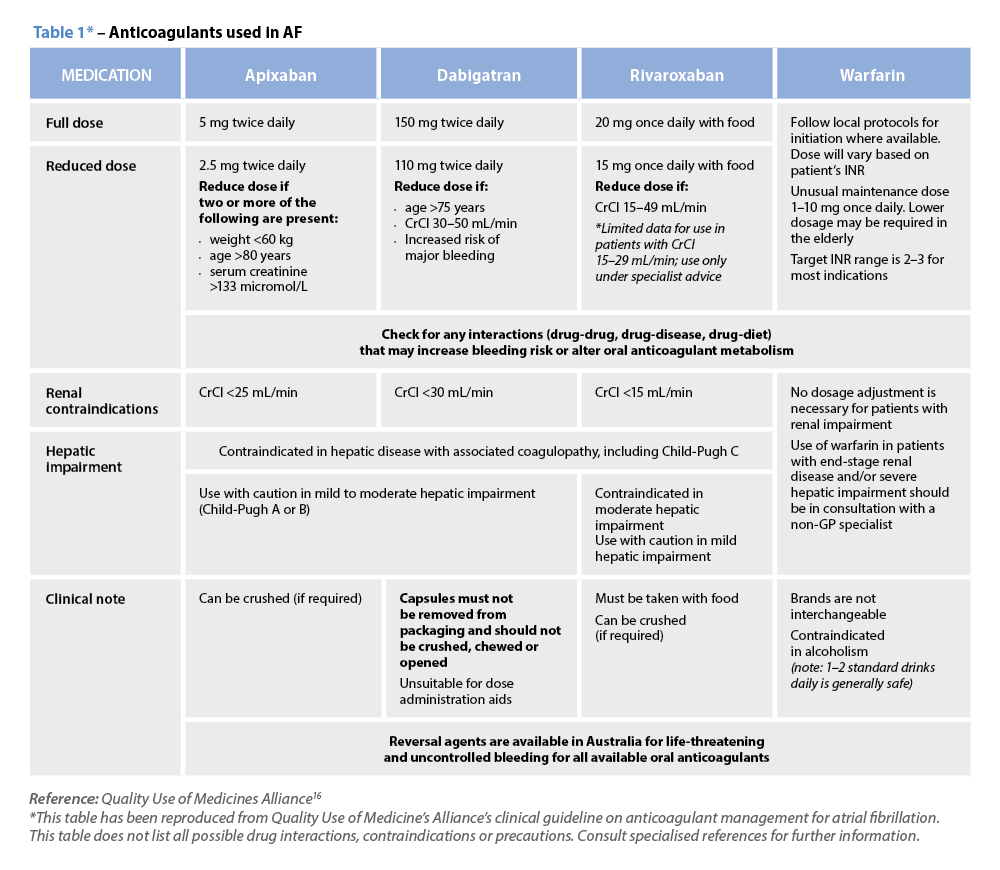

C – Comorbidity and risk factor management Warfarin

Warfarin