In the second of a six-part series, we expand on the PSA Choosing Wisely recommendations, taking a closer look at polypharmacy.

The PSA’s Choosing Wisely recommendations includes a statement about polypharmacy and deprescribing (Box 1).1-8 PSA’s statement recognises that while medications can be of great benefit to people, the same medications have the potential to also cause harm. It acknowledges the need for ongoing comprehensive medication reviews that consider the ongoing benefit.

BOX 1. The recommendation |

|

| Do not prescribe medications for patients on five or more medications, or continue medications indefinitely, without a comprehensive review of their existing medications, including over-the-counter medications and dietary supplements, to determine whether any of the medications or supplements should or can be reduced or discontinued. | The use of medications for older people can improve symptom control and reduce disease progression. However, the use of five or more medications is independently associated with poor clinical outcomes including increased hospital admissions, falls and premature mortality. Deprescribing (which is the process of discontinuing or reducing medications) is an intervention to improve the quality use of medicines. Deprescribing is an intervention to manage polypharmacy that requires balancing the potential benefit and harm of each medication then systematically withdrawing medications that are no longer needed or clinically indicated or are inappropriate for that individual at that time. There is a growing body of evidence to support deprescribing in older people. |

Good medication management includes starting new medications, adjusting current medications, and stopping those medications that are no longer required. Over time the original condition the medicine was prescribed for can change as can the patient’s overall goals and health, including renal function and clearance of a medicine. This process includes ongoing review to consider whether each medication continues to be indicated, or whether the indication has resolved or an alternative management strategy could be more beneficial. It also involves an assessment of whether a medication is efficacious in that individual for that condition.

The use of five or more medications is commonly known as polypharmacy, though this term is also used to mean more medications than clinically necessary. Increasing numbers of medications are associated with many poor clinical outcomes including falls, frailty, hospital admissions, adverse drug effects, interactions, impaired cognition and premature mortality.9-14 People using many medications are more likely to use potentially inappropriate or unnecessary medications.15,16 They are also more likely to not be prescribed one or more clinically indicated medications, known as underprescribing, which means they are missing out on the potentially beneficial outcomes of these medications.16-18

Deprescribing is an intervention to optimise medication use by reducing the number of medications used. The deprescribing process balances the potential benefits of the medication with the potential for harm from the medication.6 The consumer’s preferences and treatment goals need to be discussed and considered.4,8 Some medications can be withdrawn abruptly, but others need to be tapered to avoid rebound or withdrawal symptoms.8 Ongoing monitoring of the patient is required for many medications to ensure that the condition remains stable.

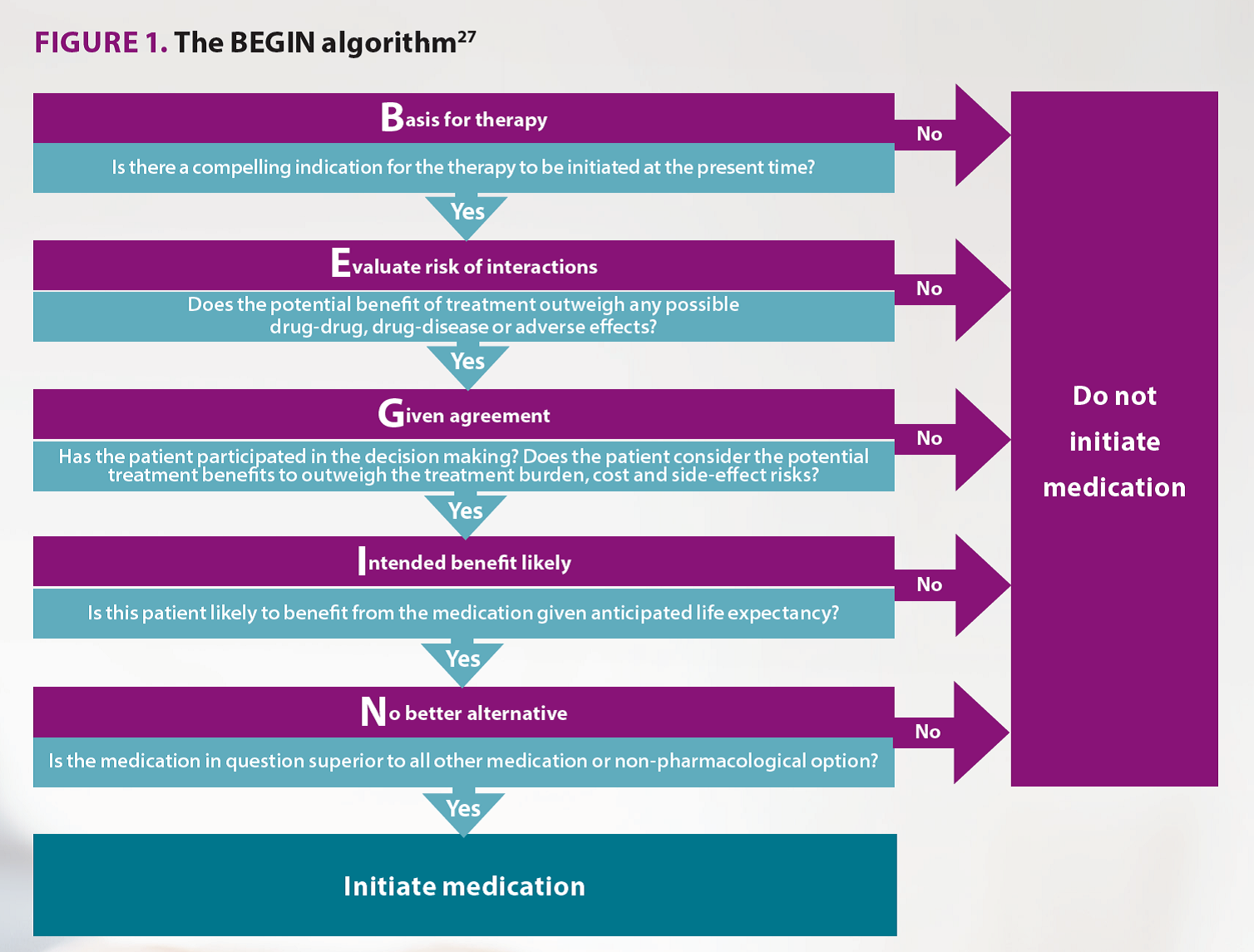

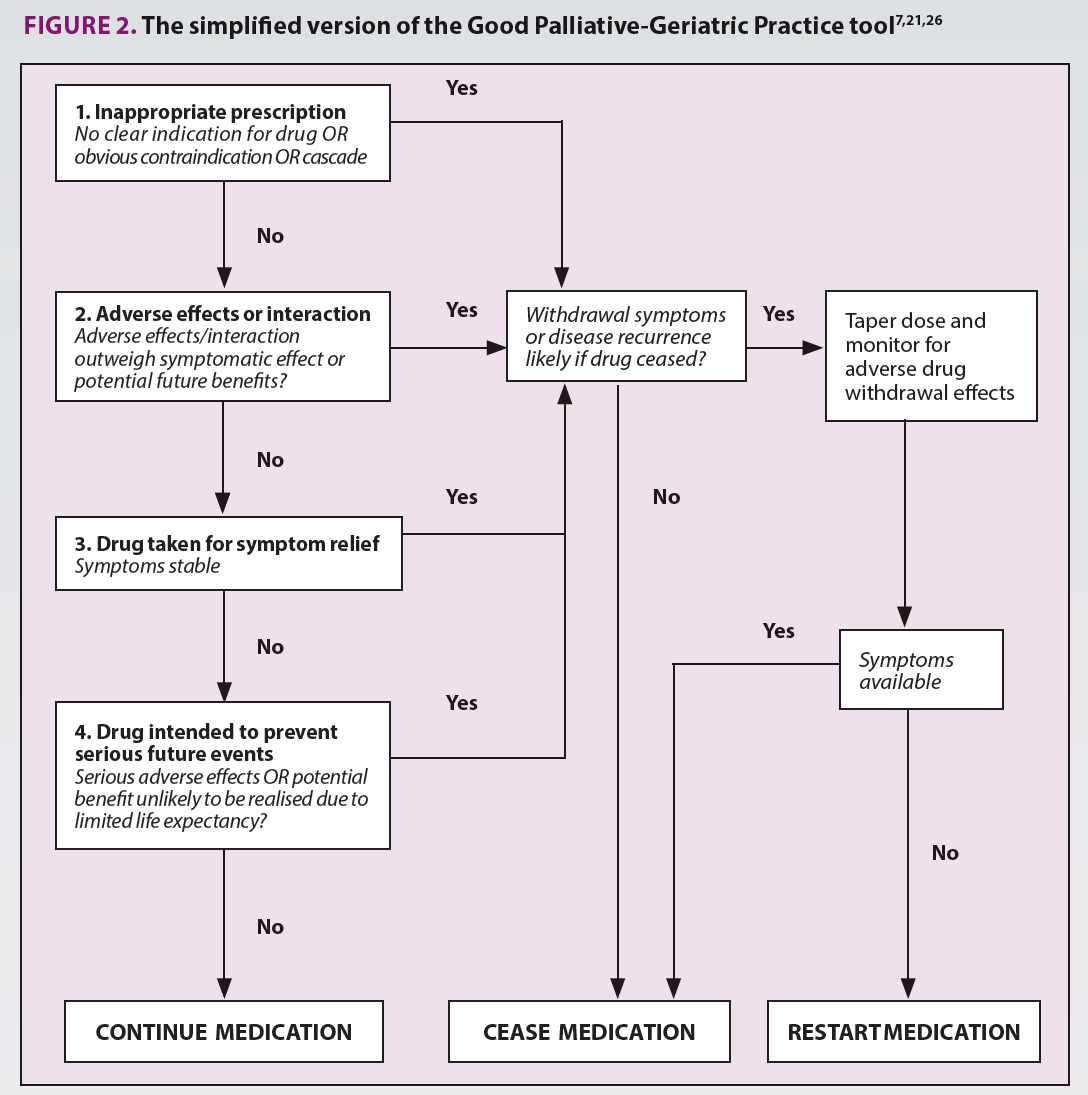

Consideration of all medications is important. Herbal medications and nutritional supplements can have pharmacologically active effects on the body, which contributes to polypharmacy regardless of efficacy. For example, a systematic review of herbal medications for insomnia found that valerian had similar safety profile to benzodiazepines though with less benefit.19 Therefore, these complementary and alternative medications need to be considered similarly to other medications in regards to their contribution to polypharmacy. Experienced doctors and pharmacists come to similar conclusions and recommendations in their assessment of polypharmacy and the potential for harm, as well as medications that can be potentially be stopped.20,21 Several tools exist to help pharmacists assess medication use.22 Multiple explicit lists of medications exist to identify medications that pose an increased risk for older people, including the STOPP/START criteria or the Beers criteria, or the MATCH-D criteria that is specific for people living with dementia.23-25 Implicit tools to support clinician judgment exist too. The deprescribing tool is a validated tool that has been tested in randomised controlled trials (Figure 2).7,21,26 It assists the pharmacist to consider whether the medication is appropriate, the adverse effects compared to the benefits, current symptoms and the potential for benefit. The BEGIN algorithm is useful when considering starting a new medication (Figure 1).27 This algorithm considers the potential for benefit and for non-pharmacological interventions.

Pharmacists have an important role in managing appropriate medication use and optimising regimens. Where there are multiple prescribers, it can sometimes be only at the pharmacy or during a medication review where a clear picture of the entire medication regimen is gained when taking a best available medication history. Active participation in reviewing the ongoing medication use, and potential to de-escalate therapy, is a key role for the pharmacist.

TABLE 1. Deprescribing resources |

|

| NPS MedicineWise | www.nps.org.au/topics/ages-lifestages/for-individuals/older-people-and-medicines |

| MedStopper | www.Medstopper.com |

| Canadian Deprescribing Network | www.Deprescribing.org |

| Tasmanian Primary Health Network | www.primaryhealthtas.com.au/for-health-professionals/resources/?keyword=&cat=medicines |

To learn more about deprescribing, see the CPD module Deprescribing in the elderly.

References

- Martin, P., et al., Eff ect of a pharmacist-led educational intervention on inappropriate medication prescriptions in older adults: the D-PRESCRIBE randomized clinical trial. Jama, 2018. 320(18): p. 1889-1898. At: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30422193

- Reeve, E., W. Thompson, and B. Farrell, Deprescribing: a narrative review of the evidence and practical recommendations for recognizing opportunities and taking action. European journal of internal medicine, 2017. 38: p. 3-11. At: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28063660

- Scott, I.A., et al., First do no harm: a real need to deprescribe in older patients. Med J Aust, 2014. 201(7): p. 390-392. At: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25296059

- Page, A., et al., A concept analysis of deprescribing medications in older people. Journal of Pharmacy Practice and Research, 2018. 48(2): p. 132-148. At: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jppr.1361

- Page, A.T., et al., The feasibility and effect of deprescribing in older adults on mortality and health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 2016: p. 583-623. At: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27077231

- Page, A.T., et al., Deprescribing in older people. Maturitas, 2016. 91: p. 115-134. At: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/304143731_Deprescribing_in_Older_People

- Potter, K., et al., Deprescribing in Frail Older People: A randomised controlled trial. PLoS ONE, 2016. 11(3). At: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26942907

- Potter, K., et al., Deprescribing: A guide for medication reviews. Journal of Pharmacy Practice and Research, 2016. 46(4): p. 358-367. At: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311616505_Deprescribing_A_guide_for_medication_reviews

- Gnjidic, D., et al., Polypharmacy cutoff and outcomes: five or more medicines were used to identify community-dwelling older men at risk of different adverse outcomes. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 2012. 65(9): p. 989-95. At: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22742913

- Hilmer, S.N. and D. Gnjidic, The Effects of Polypharmacy in Older Adults. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 2009. 85(1): p. 86-88. At: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19037203

- Hajjar, E.R., A.C. Cafi ero, and J.T. Hanlon, Polypharmacy in elderly patients. The American journal of geriatric pharmacotherapy, 2007. 5(4): p. 345-51. At: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18179993

- Turner, J.P., et al., Polypharmacy cut-points in older people with cancer: how many medications are too many? Support Care Cancer, 2015. At: https://www.mascc.org/assets/Pain_Center/2015_October/oct2015-5.pdf

- Gnjidic, D., et al., Polypharmacy cutoff and outcomes: Five or more medicines were used to identify community-dwelling older men at risk of different adverse outcomes. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 2012. 65(9): p. 989-995. At: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22742913

- Heuberger, R.A. and K. Caudell, Polypharmacy and nutritional status in older adults: A cross-sectional study. Drugs and Aging, 2011. 28(4): p. 315-323. At: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21428466

- Steinman, M.A., et al., Polypharmacy and prescribing quality in older people. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 2006. 54(10): p. 1516-1523. At: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17038068

- Ryan, C., et al., Potentially inappropriate prescribing in older residents in Irish nursing homes. Age and Ageing, 2013. 42(1): p. 116-120. At: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22832380

- Kuijpers, M.A.J., et al., Relationship between polypharmacy and underprescribing. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 2008. 65(1): p. 130-133. At: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17578478

- Cherubini, A., A. Corsonello, and F. Lattanzio, Underprescription of beneficial medicines in older people: Causes, consequences and prevention. Drugs and Aging, 2012. 29(6): p. 463-475. At: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22642781

- Leach, M. and A. Page, Herbal medicine for insomnia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 2015. At: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25644982

- Ong, G.J., et al., Clinician agreement and influence of medication-related characteristics on assessment of polypharmacy. Pharmacology Research and Perspectives, 2017. 5(3). At: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5464348/

- Page, A.T., et al., Deprescribing in frail older people – Do doctors and pharmacists agree? Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 2016. 12(3): p. 438-449. At: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282530618_Deprescribing_in_Frail_Older_People_-_Do_Doctors_and_Pharmacists_Agree

- Scott, I., K. Anderson, and C. Freeman, Review of structured guides for deprescribing. Eur J Hosp Pharm, 2017. 24(1): p. 51-57. At: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6116772/

- Page, A.T., et al., Medication appropriateness tool for co-morbid health conditions in dementia: consensus recommendations from a multidisciplinary expert panel. Internal Medicine Journal, 2016. 46(10): p. 1189-1197. At: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27527376

- O’Mahony, D., et al., STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: Version 2. Age and Ageing, 2015. 44(2): p. 213-218. At: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25324330

- The American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel, American Geriatrics Society 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 2015. 63(11): p. 2227-46. At: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26446832

- Garfinkel, D., S. Zur-Gil, and J. Ben-Israel, The war against polypharmacy: A new cost-effective geriatric-palliative approach for improving drug therapy in disabled elderly people. Israel Medical Association Journal, 2007. 9(6): p. 430-434. At: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17642388

- Parekh, N., et al., A practical approach to the pharmacological management of hypertension in older people. Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety, 2017. 8(4): p. 117-132. At: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5394506/

See PSA’s six recommendations to the Choosing Wisely medicine safety campaign at: www.psa.org.au/choosing-wisely/

BY PSA CHOOSING WISELY WORKING PARTY: CHRIS CAMPBELL, DR AMY PAGE, SUE EDWARDS, A/PROF REBEKAH MOLES, DR KENNETH LEE, ALYSSA PISANO, DR SHANE JACKSON & DR CHRIS FREEMAN

‘We’re increasingly seeing incidents where alert fatigue has been identified as a contributing factor. It’s not that there wasn’t an alert in place, but that it was lost among the other alerts the clinician saw,’ Prof Baysari says.

‘We’re increasingly seeing incidents where alert fatigue has been identified as a contributing factor. It’s not that there wasn’t an alert in place, but that it was lost among the other alerts the clinician saw,’ Prof Baysari says.