Adapted by Ann Winkle MPS.

Regulatory bodies are warning of the potential for diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) as a serious complication of sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor therapy, particularly in people who undergo surgical or medical procedures.1

Many patients presenting with SGLT2 inhibitor-induced DKA are euglycaemic, making it difficult to identify as blood glucose levels (BGLs) and ketone levels can be near normal.1

Case study

A 60-year old man was admitted to hospital for a bilateral hemi-knee replacement.

His regular medicines were:

| Medicine | Strength | Dose |

|---|---|---|

| Empagliflozin/metformin | 12.5/1,000 mg | ONE tablet twice daily |

| Telmisartan/hydrochlorothiazide | 80/12.5 mg | ONE tablet in the morning |

| Esomeprazole | 20 mg | ONE tablet in the morning |

| Rosuvastatin | 20 mg | ONE tablet in the morning |

Empagliflozin/metformin was ceased 3 days prior to surgery and recommenced the day after surgery while still an inpatient. Two days after the operation he became unwell with an increased respiratory rate.

Pathology results

| Test | Result | Normal Range |

|---|---|---|

| pH | 7.26 | (7.35–7.45) |

| pCO2 | 46.8 mm Hg | (35–46 mm Hg) |

| Potassium | 3.12 mmol/L | (3.6–4.8 mmol/L) |

| Anion gap | 14.0 | (< 12) |

| Lactate | 2.49 mmol/L | (0.00–1.30 mmol/ L) |

| Bicarbonate | 21.3 mmol/L | (22–32 mmol/L) |

Discussion

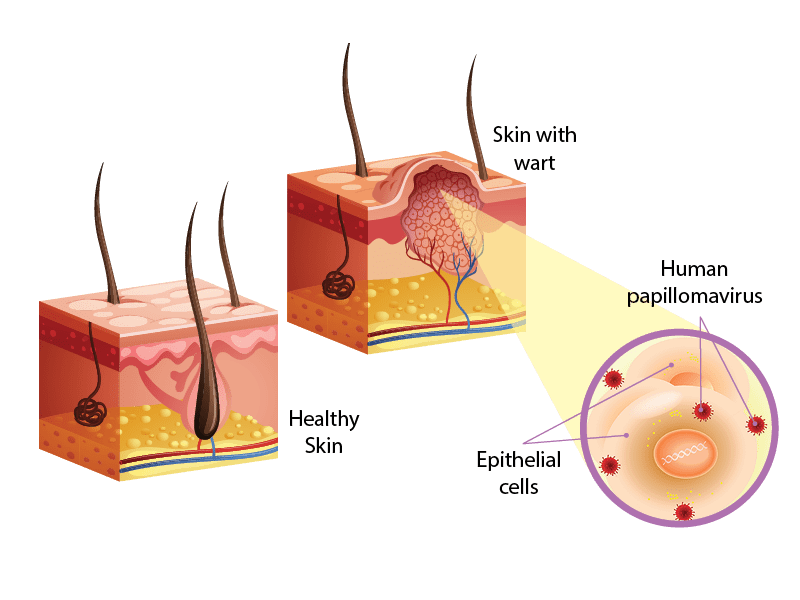

Sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors add to the armament for treating type 2 diabetes, with a mode of action that is independent of beta-cell function in the pancreas. They inhibit SGLT-2 proteins located in the renal tubules responsible for reabsorbing glucose back into the blood. As a result, more glucose is excreted in the urine.

SGLT2 inhibitors carry a low risk of hypoglycaemia and are usually well tolerated. However, diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), including euglycaemic DKA (euDKA), has emerged as a challenging adverse effect. One possible mechanism is that SGLT2 inhibitors blunt insulin production in the face of stress hormones leading to increased ketotic metabolism.2

DKA is an acute complication of diabetes in which ketone bodies build up in the blood. Early signs and symptoms, typically developed over 24 hours, include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, excessive thirst, difficulty breathing, unusual fatigue and sleepiness. DKA typically presents with high glucose levels, however, atypical euDKA may occur at lower levels. If DKA is not diagnosed early and treatment initiated more serious signs and symptoms including dehydration, deep gasping breathing, confusion and coma can develop.1

The TGA has received reports of DKA, including euDKA, associated with surgical or medical procedures requiring anaesthesia or light sedation, including cardiovascular, bariatric, orthopaedic or gastrointestinal procedures.1

DKA has also been linked to the pre- and post-surgical use of SGLT2 inhibitors (empagliflozin, dapagliflozin) in major surgery since their introduction into Australia. From March 2018 to August 2019, the TGA received a total of 219 reports of DKA (or metabolic acidosis) where empagliflozin or dapagliflozin were the suspected causative medicine. Reports include cases of SGLT2 inhibitors prescribed outside their licensed indication for type 1 diabetes.1

Other DKA risk factors are infections, gastrointestinal conditions, cardiovascular conditions, dehydration, malnourishment/reduced calorie intake and non-adherence with insulin or reductions in insulin dose.1

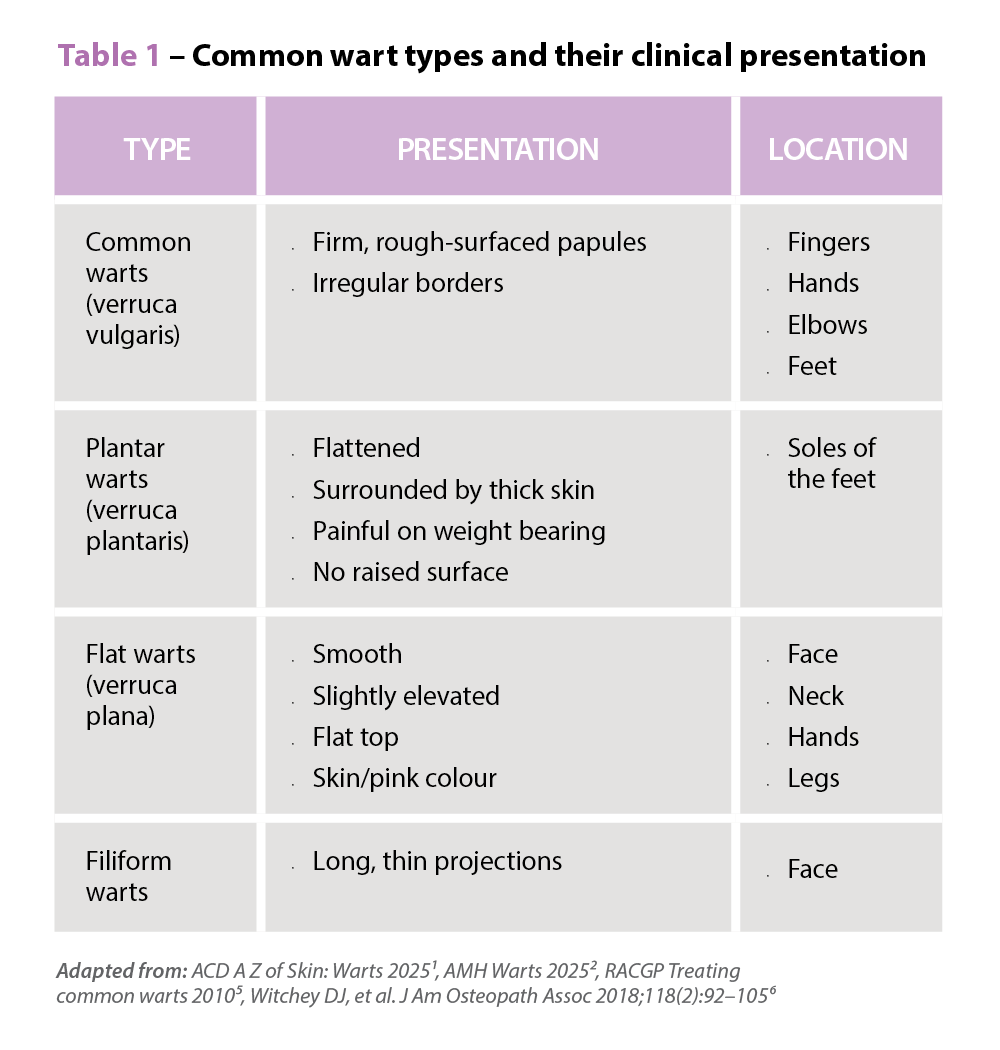

The clinical chemistry features of euDKA include2:

- Plasma pH < 7.3

- Serum bicarbonate < 18 mmol/L

- Wide anion gap > 12mmol/L (albumin corrected)

- Normal or mildly increased plasma glucose: glucose < 14 mmol/L

- Increased plasma ketones.

Case study cont.

Empagliflozin/metformin was ceased, and not recommenced during his hospital stay. BGL levels (taken 3 times daily) were usually between 4–8 mmol/L, except for 3.9 the day after empagliflozin/metformin was given. Although empagliflozin had been ceased before surgery, he may have had other risk factors (e.g. orthopaedic surgery, infection, malnourishment, insufficient post-operative oral intake). His general practitioner was informed of the case by the hospital pharmacist.

Recommendations for practice

Stop a SGLT2 inhibitor 3 days before surgery (2 days prior to, and day of surgery). An increase in other glucose-lowering medicines may be needed during this time. Routinely check blood glucose and ketone levels in the perioperative period if the patient is unwell or has limited oral intake and has been on an SGLT2 inhibitor prior to surgery. Restart when patient is eating and drinking normally.2,3

Stop an SGLT2 inhibitor earlier in bariatric surgery, where the risk of ketoacidosis may remain high for weeks or months after surgery.3

If a pharmacist is alerted to symptoms suggestive of ketoacidosis (e.g. unexplained severe vomiting and abdominal pain) they should refer the patient to their treating doctor, even if glucose appears normal (note that urinary ketone testing may be unreliable).3

References

- Therapeutic Goods Administration. Safety information; Alert – Sodium glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors: Safety advisory – diabetic ketoacidosis and surgical procedures. TGA 2018.. At: www.tga.gov.au/alert/sodium-glucose-co-transporter-2-inhibitors

- Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists. Safety alerts Severe euglycaemic ketoacidosis with SGLT2 inhibitor use in the perioperative period. ANZA; 2018 At: www.anzca.edu.au/fellows/safety-and-quality/safety-alerts/severe-euglycaemic-ketoacidosis-with-sglt2-inhibit

- Rossi S, ed. Australian medicines handbook. Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook; 2019.

John Wilks MPS is a Clinical Pharmacist at Campbelltown and Norwest Private Hospitals.

Symptoms

Symptoms