Gradual specialisation – from dispensing to medical emergency teams.

Pharmacists working in the hospital setting were once limited to the dispensary. This changed to include ward-based clinical pharmacy services and has now evolved even further to pharmacist specialisation.

Significantly, they are part of the medical emergency team (MET) in some of the larger hospitals. In these settings hospital pharmacists continue to evolve their practice and demonstrate how vital they are in wide-ranging multidisciplinary teams while helping improve patient outcomes.

Hospital pharmacy is now the fastest growing sector of the profession – and the preferred option for many pharmacy students who join the workforce each year. Now 23% of the profession, hospital pharmacists have grown from about 4,000 in 2013 to 6,100 in 2021.1

Like community pharmacists and pharmacists in other practice settings, hospital pharmacists have had to innovate lately during an ‘explosion of activity’, including digitisation, and increased work demands and working hours during the COVID-19 pandemic.1

COVID-19 vaccination by pharmacists, for example, began in hospitals, as did assistance with antiviral medicines delivery. Other examples include at Westmead Hospital in Sydney, where three-way video interpreters were set up chair side via iPADs on stands to reduce contact with cancer patients. Take-home medicine packs were tailored to patient requirements.2

The COVID-19 pandemic, meanwhile, accelerated and drove the shift from face-to-face hospital outpatient clinics to digital methods, the use of devices, video conferencing and remote monitoring of COVID-positive patients through various hospital-in-the-home (HiTH) programs, as well as iterations of programs in hospitals including the Canberra Hospital’s COVID Care@Home program3 with pharmacist advisers.

Pharmacists also undertake advanced training residencies in areas including critical care, mental health and respiratory, as well as specialisations in analgesia and antimicrobial stewardship. At the recent International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP) Congress in Seville, Spain, sessions highlighted opportunities to input episodes of care into digital health records, enabling shared information with multiple healthcare providers, which include vaccination records uploaded into the Australian Immunisation Register and discharge medications summaries sent to an individual’s My Health Record. Expanding these digital efficiencies can support pharmacists working to their full scope of practice, reduce duplication of activities, and improve safety at transitions of care, attendees were told.

During a recent trial in New South Wales, a virtual clinical pharmacy service focusing on core hospital pharmacist tasks was implemented in eight rural and remote hospitals. These hospitals otherwise did not have access to an on-site hospital pharmacist, thereby enabling access to hospital pharmacists skills and medicines knowledge to provide a model for policymakers.4

Specialisations

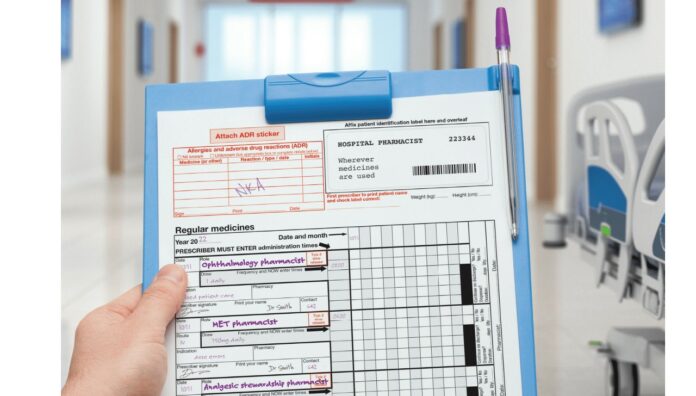

In tertiary hospitals, including Perth’s Fiona Stanley Hospital, increasingly specialised roles have been implemented, such as partnered charting pharmacist role.5 And pharmacists now specialise in areas where they previously had minimal involvement – like Ljubica Bukorovic, AP‘s ocular subject matter expert, at the Princess Alexandra Hospital in Brisbane. She was likely the only ophthalmology pharmacist in Australia when she started just 4 years ago, but she’s not alone now.

Likewise, Dr Troy Wanandy MPS remains one of the few allergy and immunology specialist pharmacists (see Box 1). There are now more, at least one in Brisbane.

Other relatively new pharmacist specialisations include work in clinics with gastroenterology, brain injury, nephrology and renal transplant patients, to name just a few outside the traditional scope of hospital pharmacy. These pharmacists interact in multidisciplinary teams of doctors, nurses and allied health services to ensure medicines optimisation and coordination of care with primary and secondary care providers. They can often provide clinical consulting services to other areas of a hospital from the speciality areas of knowledge they have gained.

The learning, challenges and collaborations that specialisation provides pharmacists – often in outpatient clinics, but also on wards – adds to the collegiality felt from working with experts in a variety of fields, several hospital pharmacists told AP. As well, pharmacists often experience growing appreciation by various medical specialists for pharmacist services, and the education they can provide – all geared for better treatment outcomes for patients.

Emergency medicine pharmacists

Pharmacists are now being included as members of the MET. At the Alfred Hospital Melbourne and Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital (RBWH), pharmacists are passionate about their roles in established emergency medicine (EM) teams in the emergency department (ED).

Pharmacists contribute to a hospital MET with their unique skillset, knowledge and ability to perform under pressure to provide clinical advice on medicine dosing, administration and IV compatibility, and to ensure medicines can be easily located in an emergency (see Patient deterioration and advanced life support medicines). Resuscitation, for instance, has not been a traditional practice area for pharmacists. With the development of EM clinical pharmacy, pharmacists are now involved.

EM at The Alfred

The ‘unique skillset’ of hospital pharmacists for upfront decision-making across the spectrum of patient presentations is revolutionising the management of patients presenting to EDs, according to Cristina Roman, Lead Pharmacist at Alfred Health’s Emergency and Trauma Centre (ETC).

For the past 12 years (and feeding into the PhD she is due to complete shortly), Ms Roman has built an area of expertise around the positive impact pharmacists can have in resuscitation and presentation of critically unwell patients. ‘There is often little consideration given to the optimisation of medication therapy in this high acuity setting, where the potential for medication errors is high,’ she says.

Also, she adds, there is the potential for medicine-related problems due to the pressure to make rapid decisions, coupled with the ‘high risk’ nature of medicines commonly used and often with little clinical information available immediately on which to base crucial next steps. To that end, Ms Roman has focused her research and development of the clinical services she leads into three areas of practice involving EM pharmacists:

- code strokes and improving time to thrombolysis administration6

- sepsis alerts and improving time to antibiotic administration, particularly for patients who need ICU care

- trauma calls and improving time to analgesia and medicine management.

EM pharmacists are involved in upfront decision-making on immediate treatment options with senior medical staff, she says. ‘They are responsible for charting these medications via the Partnered Pharmacist Medication Charting (PPMC) model of care, 7–9 drawing up medications required for immediate administration by the nurse and ensuring that home medications are considered early on in the patient journey. ‘Rather than seeing this as a job previously done by doctors or nurses, I see this as pharmacists filling a gap and complementing the current expertise in the team as the medicines experts,’ she says.

Box 1– Dr Troy Wanandy

| DR TROY WANANDY BPharm, MSc, PhD, MPS

Senior Specialist Pharmacist in Clinical Immunology and Allergy, Royal Hobart Hospital One of the few hospital pharmacists specialising in clinical immunology in Australia, Dr Troy Wanandy is an Adjunct Researcher in the College of Health and Medicine at the University of Tasmania, where he leads the Jack Jumper venom allergy research group. He is also the Quality Manager for the Jack Jumper Program12 started more than 2 decades ago as a state-funded project at Royal Hobart Hospital. The original aim of the small team of researchers was to establish whether venom immunotherapy, a treatment to prevent life-threatening anaphylaxis from jack jumper ant stings in otherwise healthy people, could be made from ant venom components. The painful sting of the jack jumper ant (Myrmecia pilosula), an aggressive native ant, can cause allergic reactions, including systemic anaphylaxis in humans and animals. Known also as the jumper ant, hopper ant, jumping jack, black jumper and jackie jumper, it is one of the few ant species, anywhere, known to kill humans. The sting of the ant in Tasmania alone is responsible for more cases of anaphylaxis than bee stings, and about 3% of Tasmanians are allergic.12 It is found mainly in Tasmania, Victoria, and South Australia – and the Tasmania Jack Jumpers National Basketball League team (‘a deadly new threat’ with a ‘fierce local mascot’) is named after it.13 When the treatment proved efficacious, the hospital was granted a licence by the Therapeutic Goods Administration in 2008 to manufacture jack jumper ant venom immunotherapy products.14 Since then, Dr Wanandy has been responsible for ensuring the safety, quality and efficacy of the products manufactured and distributed to the most-affected states. In 2022, the Jack Jumper Program evolved into Australia’s newest Department of Clinical Immunology and Allergy. It now boasts two clinical immunologists, a rheumatologist, six highly experienced nurses and nurse immunisers, three specialist pharmacists, two specialist pharmacy technicians and four medical scientists. |

Improved patient outcomes

Until recently much of the evidence for better patient outcomes, as a result of EM pharmacists working in EDs, was centred in the United States. In addition, a systematic review10 published by Ms Roman showed that early involvement of pharmacists during resuscitation is an emerging area of practice, in addition to EM pharmacist involvement in antimicrobial stewardship and charting of medicines for patients.

‘EM pharmacy services across Australia Are slowly shifting to include EM pharmacist involvement in resuscitation, which is now strongly encouraged in the Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia’s Standard of Practice in Emergency Medicine For Pharmacy Services,’ Ms Roman says.11

EM at the RBWH

The RBWH is the only hospital in Queensland with an advanced scope pharmacy service which operates from 7am to 11 pm, 365 days a year. The hospital’s expanded pharmacist service in the ETC has been running for 5 years. Originally building on one, often part-time pharmacist, in place since 2010, the extended scope mEDicineWise project that began in 2017 was built on principles including those of the Choosing Wisely Program and the National Prescribing Service (NPS).

The success of the mEDicineWise project has allowed the team to evolve into an ‘integrated, expected and respected part of the multidisciplinary emergency team’, says Elizabeth Doran, the ETC’s Lead Clinical Pharmacist.

The team now consists of Ms Doran, three senior specialist pharmacists, and a junior training position, equating to almost five full-time positions. Contributing to improved medicine use for every patient (self-referrals or requested consultations), the team attends and reviews new patients from the ambulance ramp, to a chair, to beds in fast-track, acute, resuscitation and trauma suites, or those awaiting inpatient beds or transfer to/discharge from a short-stay unit.

Prioritisation is given to patients who may benefit from a pharmacist review for a variety of reasons with a range of assessment techniques including age, gender and problem noted by a triage nurse. Pharmacists have developed the art form of a ‘strong index of suspicion’, says Ms Doran.

Medicine-related problems

Pharmacist input into the team adds value to patient care by looking at problems through a medicine lens. Typically, Ms Doran explains, this means the focus is on patients presenting with (or a suspicion of) a medicine-related problem. ‘This can be an adverse event (e.g. haemorrhages in patients using anticoagulants, abnormal blood results or allergy), under-utilisation of therapy/poor compliance (think inadequate analgesia, missed doses of anti-epileptics, inappropriate choice or dosing of antibiotics), or toxic effects (e.g. hypotension and a fall from rapidly titrated doses of antihypertensives, accumulation of medicines in kidney failure, management of overdoses),’ she says.

ETC pharmacists at the RBWH also ensure patients who require complex treatment or review and optimisation are provided with a high level of care.This may include, for instance, a patient with a gastrointestinal haemorrhage where the pharmacist can identify whether anticoagulants or NSAIDs may have precipitated the problem and can advise on:

- prescribing a necessary reversal agent

- ensuring all appropriate therapies are considered and prescribed

- advising on administration techniques, such as those in which medicines are incompatible with each other in a patient with limited intravenous access.

Pharmacist’s role and cognitive load assistance

Pharmacists in these roles provide cognitive load assistance to doctors and nurses to allow them to focus on other aspects of an emergency. It is essential that medicine problems are identified and mitigated early in the patient’s entry to the ED. This can enable an early discharge or, otherwise, for those admitted, there is a plan in place (utilising their medication history) to reduce total length of stay. In addition, a pharmacist’s role is to ensure that similar problems with medicines initiated or changed during the ED stay are avoided, says Ms Doran.

Liaison with general practitioners and community pharmacies to gather information and plan for safe, effective discharge is also necessary.

‘We have created a unique role where we are part of the team right from the initial notification of the impending arrival of a critically unwell patient,’ Ms Doran says. At this point, pharmacists gather relevant information about the patient – for instance, from their My Health Record – about allergies, and any documented advance care or health directive. Ms Doran says feedback has shown that this role is invaluable in informing risk assessment and assisting resuscitation.

Reconstitution of medicines, and assisting nurses in manufacture at the bedside where needed, is also part of the role. In large-scale traumas in the ED, she points to pharmacists’ ‘significant role in suggesting and optimising the safe dosing and administration of multiple medications and blood products in particular’.

‘This is the cognitive load assistance we offer the doctors and nurses in making time-critical therapeutics and medication management as safe as possible in an emergency,’ Ms Doran explains.

Positive impact

Currently, about 25% of patients admitted from the ED to any inpatient unit are reviewed by the ED pharmacist, she says.

And in recent years, she says the time to first-pharmacist review for medical patients has been reduced from approximately 30 hours to 6 hours. Various studies show specialist pharmacists active in the ED have resulted in reduced time to:

- antibiotics17

- thrombolysis in cardiovascular events6,18

- post-intubation sedation/analgesia19

- improved dose optimisation of antiepileptics in status epilepticus.20

Moving forward

Results are expected in 2024 from the nearly 3-year Transitions of Care Pharmacy Program, in three Queensland hospitals – RBWH and the Princess Alexandra and Townsville University Hospitals.

It was initiated in March 2021 as a Queensland Government election commitment to PSA, to improve clinical handover across healthcare settings.21

Meanwhile, Ms Roman finds it rewarding that her medicines expertise is having a direct and ‘often profound impact’ on patient care in the ED. ‘After working as a clinical pharmacist in a number of rotational roles previously, I can honestly say there are very few other opportunities for pharmacists that compare to this, and I am very excited to be leading the way forward in these advanced areas of practice in Australia.’

Among the range of other advanced practice roles for pharmacists in different specialties and residency programs are attendances at Code Blues (a patient in a medical emergency) and MET calls for patients – with ‘many more opportunities for expansion of roles for clinical pharmacists’ to come, she says. Ms Doran also sees ‘a lot of scope’ for developing the pharmacist’s role in EM. These could include (with legislative change and accredited training) pharmacist practitioners like the Advanced Clinical Practitioner in the UK National Health Service, and, following the success of partnered charting in many sites (and The Alfred’s Chart It First initiative), independent prescribing is a potential ‘next step to develop in the near future’.

There is also scope, she believes, for pharmacists to lead microbial culture and sensitivity follow-up after ED discharge, and to link in with primary health to inform them of antibiotic choice and tailored dosing for organ function. ‘Pharmacists actively contributing in resuscitation and trauma is progressive and exciting,’ says Ms Doran, and ‘contributing to high-level dynamic clinical decision-making in the acute critical care space is challenging but immensely rewarding.’

References

- The Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia. Pharmacy Forecast Australia 2022. 2022. At: https://bit.ly/3CyPARx

- The Pulse. Celebrating the work of an essential support network: the pharmacists of western Sydney. 2022. At: https://thepulse.org.au/2022/09/24/celebrating-the-work-of-an-essential-support-network-the-pharmacists-of-western-sydney/

- ACT Government. Canberra Health Services. Covid Care@Home Program. 2022. At: www.canberrahealthservices.act.gov.au/services-and-clinics/services/covid-care@home-clinic

- Chambers B, Fleming C, Packer A, et al. Virtual clinical pharmacy services: a model of care to improve medication safety in rural and remote Australian health services. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2022;79(16):1376–84.

- Hitchen S, Sinclair V, McLennan C, et al. Safer prescribing with partnered pharmacist charting in the acute medical setting. Government of Western Australia, South Metropolitan Health Service, Fiona Stanley Fremantle Hospitals Group, Annual Improve Conference. 2018.

- Roman C, Cloud G, Dooley M, et al. Involvement of emergency medicine pharmacists in stroke thrombolysis: a cohort study. J Clin Pharm Ther 2021;46(4):1095–1102.

- Tong EY, Roman CP, Smit DV, et al. Partnered medication review and charting between the pharmacist and medical officer in the emergency short stay and general medicine unit. Australas Emerg Nurs J 2015;18(3):149–55.

- Safer Care Victoria. Partnered pharmacist medication charting (PPMC) scaling project. At: www.safercare.vic.gov.au/improvement/projects/mtip/ppmc

- Tong EY, Phuong UH, Edwards G, et al. Partnered pharmacist medication charting (PPMC) in regional and rural general medical patients. Aust J Rural Health 2022. Epub 2022 Jul 8. At: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35802809/

- Roman C, Edwards G, Dooley M, et al. Roles of the emergency medicine pharmacist: a systematic review. Pract Res Reports 2018;75(11):796–806.

- Welch S, Currey E, Doran E, et al. Standard of practice in emergency medicine for pharmacy services. J Pharm Pract Res 2019;49:570–84.

- Tasmanian Government. Jack Jumper Program. 2021. At: www.health.tas.gov.au/health-topics/allergies/jack-jumper-program

- Tasmania Jack Jumpers Official NBL Website.2022. At: www.jackjumpers.com.au/pages/brand-story Welch S, Currey E, Doran E, et al. Standard of practice in emergency medicine for pharmacy services. J Pharm Pract Res 2019;49:570–84.

- Mullins R, Brown SGA. Med J Aust 2014. Ant venom immunotherapy in Australia: the unmet need;201(1);33–4.

- Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia. Hospital pharmacy workforce at a glance. 2022. At: https://bit.ly/3C6owaR

- Paola S. Students snub community pharmacy. Australian Journal of Pharmacy 2022. At: https://ajp.com.au/news/students-snub-community-pharmacy/

- Ulloa V, Iturralde G. Impact of an emergency medicine pharmacist on time to antibiotic administration in sepsis patients. Crit Care Med 2022:50(1);720.

- Barbour J, Hushen P, Newman GC, et al. Impact of an emergency medicine pharmacist on door to needle alteplase time and patient outcomes in acute ischemic stroke. Am J Emerg Med 2022;51:358–62.

- Amini A, Faucett EA, Watt JM, et al. Effect of a pharmacist on timing of postintubation sedative and analgesic use in trauma resuscitations. Am J Health Sys Phar 2013;70(17):1513-17.

- Gawedzki P, Celmins L, Fischer D. Pharmacist involvement with antiepileptic therapy for status epilepticus in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med 2022;59:129–32.

- Queensland Government. Queensland Health. Transitions of Care Pharmacy Project (ToCPP) 2022. At: www.health.qld.gov.au/ahwac/html/tocpp/info.

‘We’re increasingly seeing incidents where alert fatigue has been identified as a contributing factor. It’s not that there wasn’t an alert in place, but that it was lost among the other alerts the clinician saw,’ Prof Baysari says.

‘We’re increasingly seeing incidents where alert fatigue has been identified as a contributing factor. It’s not that there wasn’t an alert in place, but that it was lost among the other alerts the clinician saw,’ Prof Baysari says.