Rapid Antigen Tests (RATs) have become the first step for diagnosing COVID-19, with PCR tests primarily now used in high-risk individuals who test negative on a RAT.

There are currently 87 COVID-19 RATs approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) for use in Australia. But not all tests are created equal, revealed new research.

Following a preliminary study on 10 Australian RATs in 2023, researchers at James Cook University (JCU) partnered with National Research Council Canada to compare the analytical sensitivity of 26 RATs currently available in Canada and/or Australia.

‘We were not satisfied with how the analytical sensitivity is disclaimed by the manufacturers,’ said co-author Associate Professor Patrick Schaeffer from JCU. ‘So the goal was to detect the tests worth taking.’

The products’ buffers were spiked with a nucleocapsid protein engineered by the researchers at various concentrations.

But only six, three of which are available in Australia, were able to detect the lowest concentration of SARS-CoV-2.

So which RATs work best?

Out of the 16 products used in the study that have been approved for use by the TGA, the best-performing RATs were Fanttest, Innoscreen, and Juschek.

‘Some RATs were 100-fold less sensitive than the best ones,’ said A/Prof Schaeffer. ‘That means you would need a 100-fold higher viral load to produce a positive result with those RATs.’

The TGA only approves RATs that have a ‘clinical sensitivity’ of at least 80% when used within 7 days of symptom onset. But the research findings indicate that the clinical data submitted by some manufacturers was ‘probably misleading’, he said.

For example, if a clinical study is conducted in a hospital among patients severely unwell with COVID-19, the clinical sensitivity could reach up to 99%.

‘That doesn’t mean if you do the test in the [community] where people have different states of infection that you will get that 99% sensitivity,’ said A/Prof Schaeffer.

Knowing which products are the best in terms of analytical sensitivity removes the ‘bias of studies’.

‘It really looks at the analytical power of performance of RAT tests,’ he added.

How does this impact pharmacists?

While A/Prof Schaeffer said it’s obviously up to pharmacists what products they opt to stock, there’s ‘no point’ selling RATs that are less sensitive than the best products available.

‘They all claim they are the best ones,’ he said. ‘[But] down the track, you may have an infection line that possibly resulted in people ending up on a ventilator, or in death.’

Now that data on the performance of RATs is accessible to pharmacists, they can opt to use it to inform their supply purchases and counselling advice to patients – particularly ahead of winter.

‘It’s particularly important to consider if your decision-making around taking a RAT is to visit your grandmother in an aged care facility, or someone in a cancer ward who is immunocompromised,’ said A/Prof Schaeffer.

What’s the future of rapid testing?

RATs are an important tool for disease control and fast-tracking infection notifications, thinks A/Prof Schaeffer.

‘We can use them, then retest the next day or 3 days later to make sure we are negative,’ he said.

But most importantly, it’s crucial to keep the RATs that perform well.

All Australian RATs tested all detected the nucleocapsid protein ‘to a certain level’. But one RAT – currently available in Canada and revoked in Australia by the TGA in 2022 – failed to detect the COVID-19 protein entirely at any level of concentration used in the dilution series.

‘We were absolutely shocked,’ said A/Prof Schaeffer.

Without ongoing quality control, the same thing could happen here.

‘The reality is, we could have situations like in Canada, where you could buy a RAT that doesn’t detect the protein at all,’ he said.

‘We need continual independent testing of RATS to keep the brandmakers on their toes, so they know people can actually test the accuracy of their RAT tests.’

This approach should also promote easier revocation of the RATs that underperform.

‘As better medical devices come in, low-performing RATs need to be pushed out,’ said A/Prof Schaeffer.

To that end, the team is aiming to secure funding to establish a watchdog program for RATs coming onto the market for respiratory viruses, particularly with combined test kits becoming more freely available.

This includes broadening the study to analyse RATs capable of detecting different strains of Influenza A and B viruses.

‘There were two RATs in this latest study which are designed to detect Influenza A and B as well as COVID-19, but neither of them detected influenza proteins particularly well,’ he said.

‘We’d like to look at how well influenza RATs can detect subtypes like H3N2, H5N1 “bird flu” and H1N1, otherwise known as swine flu.

‘We’re [also] developing the RSV protein now so we can carry on evaluating RATs and making sure brand makers know that we’re here to conduct post-market evaluation on sensitivity.’

‘We’re increasingly seeing incidents where alert fatigue has been identified as a contributing factor. It’s not that there wasn’t an alert in place, but that it was lost among the other alerts the clinician saw,’ Prof Baysari says.

‘We’re increasingly seeing incidents where alert fatigue has been identified as a contributing factor. It’s not that there wasn’t an alert in place, but that it was lost among the other alerts the clinician saw,’ Prof Baysari says.

Beyond the arrhythmia, AF often signals broader pathological processes that impair cardiac function and reduce quality of life and life expectancy.5 Many of these conditions are closely linked to social determinants of health, disproportionately affecting populations with socioeconomic disadvantage. Effective AF management requires addressing both the arrhythmia and its underlying contributors.4

Beyond the arrhythmia, AF often signals broader pathological processes that impair cardiac function and reduce quality of life and life expectancy.5 Many of these conditions are closely linked to social determinants of health, disproportionately affecting populations with socioeconomic disadvantage. Effective AF management requires addressing both the arrhythmia and its underlying contributors.4  C – Comorbidity and risk factor management

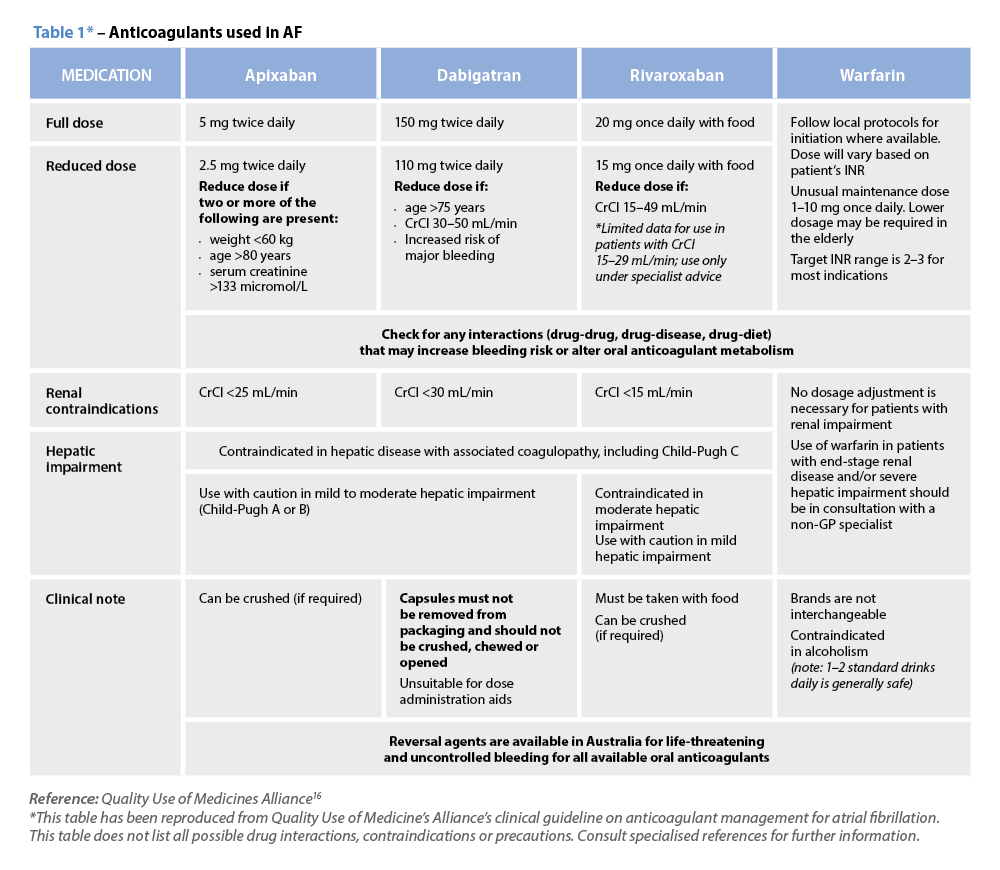

C – Comorbidity and risk factor management Warfarin

Warfarin