Credentialed pharmacists can help to change the lives of patients by taking an active role in team-based care.

From GP clinics to Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations (ACCHOs) and residential aged care facilities, credentialed pharmacists play a vital role in multidisciplinary healthcare teams.

Not only do they have the accreditation to conduct medication reviews, they are on-the-ground medicines experts who can provide education to patients and staff, conduct clinical audits and provide follow-up reviews, among other tasks.

No matter the setting, one thing is key to pharmacists’ success: building trust with other members of the healthcare team. In a study of GP pharmacists in the ACT, researchers suggested this trust could be developed by ensuring the credentialed pharmacist has a clear job description, improving awareness of what they can do, and taking the time to break down communication barriers.

When trust is present, pharmacists can have a big impact. ‘Pharmacist-GP-nurse collaboration to identify medication-related problems was reported as an important mechanism to improve integrated care and team effectiveness and reduce workload,’ the authors wrote.1

‘Participants described how making decisions for patients as a team could improve the quality of care in the general practice setting.’

PSA MIMS Credentialed Pharmacist of the Year for 2024 Brooke Shelly MPS has what she describes as a ‘portfolio career’.

She conducts Home Medicines Reviews (HMRs), works as a GP pharmacist at Ontario Medical Clinic in Mildura, Victoria, and is a clinical pharmacist at Beyond Pain, a Victorian-based consulting service providing tailored programs for chronic pain as well as chronic illness and mental health disorders. She says team-based care is fundamental to all her roles.

‘I couldn’t imagine doing pharmacy in any other way,’ Ms Shelly says. ‘The key to effective multidisciplinary team-based care lies in clearly defining each team member’s roles and responsibilities.

‘It’s not about confining yourself to “typical” roles, but leveraging each team member’s individual scope of practice to the fullest.’

For example, while Ms Shelly is a pharmacist, she also has experience in business operations, change management and leadership.

‘This means I can play a significant role in influencing the strategic direction of the clinic. I lead clinical meetings, develop new cycles of care to address gaps in our practice, and contribute to staff development and recruitment,’ she says.

‘Moreover, like the nurses in our practice, I’m also capable of administering vaccinations and providing wound care, and akin to GPs, I can manage chronic disease.

‘This adaptability is especially vital in the regions where we’re significantly affected by uneven healthcare workforce distribution.’

While credentialed pharmacists know the part they play in the wider healthcare system, Ms Shelly says it’s a message that should be spread wider.

‘As well as being the medicines experts, pharmacists are collaborators, solution seekers and champions of person-centred care.

‘Despite consistently being overlooked in multidisciplinary team descriptors, pharmacists are an indispensable component of the healthcare system,’ she says. ‘We need to be louder and prouder about the essential role that we play within a patient’s healthcare team and the Australian healthcare system at large.’

AP spoke with Ms Shelly and Yvette McGrath in Queensland (see over) about their approach to team-based care.

Case 1

Brooke Shelly MPS (she/her) Credentialed and GP pharmacist, Ontario Medical Clinic, Mildura, Victoria

Brooke Shelly MPS (she/her) Credentialed and GP pharmacist, Ontario Medical Clinic, Mildura, Victoria

We had an older patient who had been hospitalised due to heart failure exacerbation. Upon discharge, I did a medicine reconciliation and optimisation and drafted his GP management plan. I also provided vaccination services during subsequent visits.

It was clear the patient and his wife needed domiciliary services to maintain their safety and independence at home. But, despite referrals from the GP to multiple health professionals and agencies, they refused any help, and their health deteriorated.

I suggested to the GP that an HMR might be beneficial. She agreed, so I called the patient and said, ‘Hi Mr X, it’s Brooke from the clinic. Would it be ok if I came past your house on the way home to go through your medicines for Dr Y?’

Much to our surprise, he said yes. That was a result of having built rapport and trust with him.

The HMR revealed it was the patient’s wife who was concerned about getting help. She feared any visit might result in their institutionalisation, leading to their loss of independence. I mentioned a trusted colleague who could link them in with some domestic services. I also attended the home to complete a follow-up HMR when the aged care assessment was happening to further support them.

As a result, they now have access to services they were unaware of, including transport, food delivery and assistance with cleaning and gardening.

Now that their fear is gone, they have people around them to keep them as healthy and safe as possible. This experience underscores the importance of personalised care and addressing the holistic needs of patients and their families.

It’s important to remember that the person you’re caring for is the most important member of the team. Patients need to be actively involved in decision making, and we always need to ensure that what we as clinicians do is in line with the person’s goals of care – nothing we do is worthwhile if it’s at odds with that.

Case 2

Yvette McGrath MPS (she/her) Credentialed pharmacist, Cairns Queensland

Yvette McGrath MPS (she/her) Credentialed pharmacist, Cairns Queensland

I work in an ACCHO that’s about an hour and a half away from where I live in Cairns. It’s then another 40 minutes to an outreach clinic. We have a doctor, registered nurse, health workers, an amazing receptionist who keeps everyone organised – and a driver.

When we visit the clinic, we take a big bus, and patients can come and visit the doctor or the health worker. At the same time, some of us do HMRs.

One of our patients was a 69-year-old First Nations woman who had been in hospital for an extended period. The doctor wanted to see how she was, and the nurse, health worker and I went with him. It’s important to note that the nurse and health worker are both First Nations peoples, while the doctor and I aren’t.

It really helps to have those cultural connections in this setting.

While we were visiting the patient, I went through her medicine cupboard and pulled out those she didn’t need any more, such as spironolactone and perindopril, which had been ceased in hospital. The patient had also mentioned to the nurse that she hadn’t been taking all her medicines.

I did some education around why each medicine was important, and we tweaked the timing of some so that she would be more likely to take them.

We all went in as a team and did our own little bit.

I travel to the community about once a fortnight, and the impact I can have depends in part on the rest of the team.

For example, we have a lot of locum doctors at the moment. It was much easier to identify a patient who would benefit from an HMR and get a referral when we had a permanent doctor, as they know the system and the patients.

They would be really alert to who would benefit from a review so that I always had work to do when I came up.

Now, I rely on the health worker to identify people for HMRs and use their standing in the clinic to ask the locum to do referrals.

After being credentialed for over 20 years, there are still patients, doctors, nurses, carers and nurse navigators who tell me they never knew the service was available. When they find out about it, they always say how amazing it is.

Reference

- Sudeshika T, Deeks LS, Naunton M, et al. Interprofessional collaboration within general practice teams following the inclusion of non-dispensing pharmacists. J Pharm Policy Pract 2023;16:49.

‘We’re increasingly seeing incidents where alert fatigue has been identified as a contributing factor. It’s not that there wasn’t an alert in place, but that it was lost among the other alerts the clinician saw,’ Prof Baysari says.

‘We’re increasingly seeing incidents where alert fatigue has been identified as a contributing factor. It’s not that there wasn’t an alert in place, but that it was lost among the other alerts the clinician saw,’ Prof Baysari says.

Beyond the arrhythmia, AF often signals broader pathological processes that impair cardiac function and reduce quality of life and life expectancy.5 Many of these conditions are closely linked to social determinants of health, disproportionately affecting populations with socioeconomic disadvantage. Effective AF management requires addressing both the arrhythmia and its underlying contributors.4

Beyond the arrhythmia, AF often signals broader pathological processes that impair cardiac function and reduce quality of life and life expectancy.5 Many of these conditions are closely linked to social determinants of health, disproportionately affecting populations with socioeconomic disadvantage. Effective AF management requires addressing both the arrhythmia and its underlying contributors.4  C – Comorbidity and risk factor management

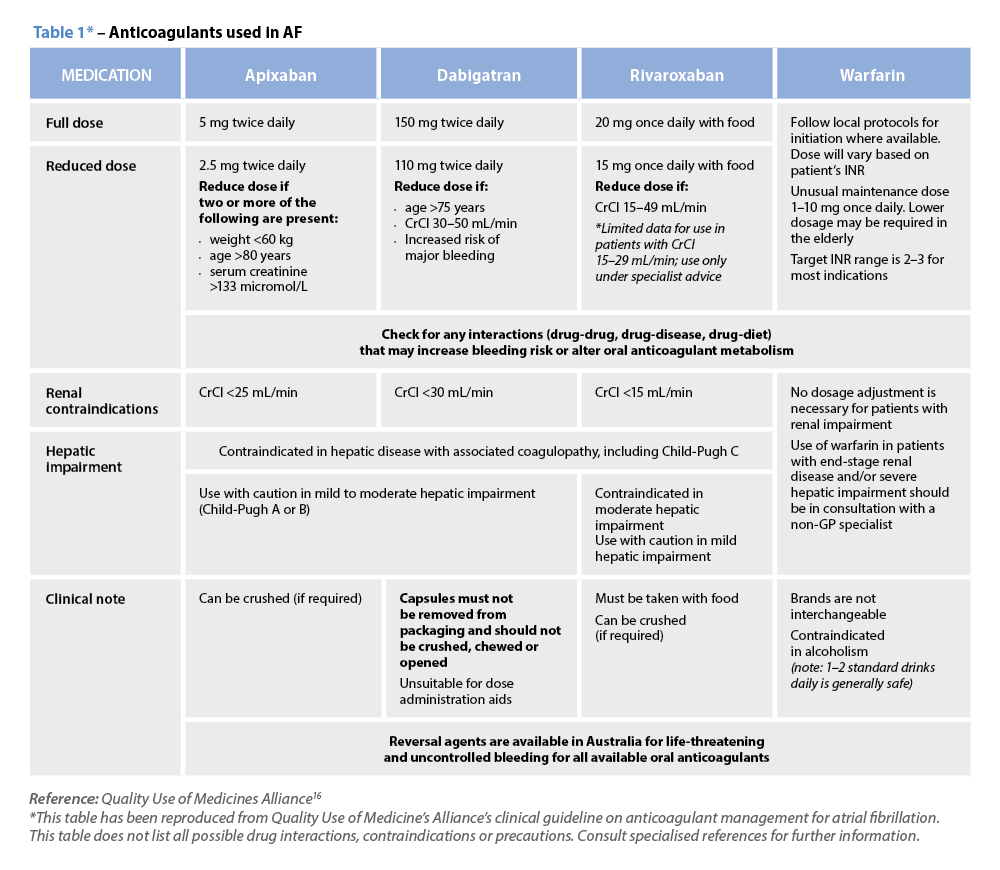

C – Comorbidity and risk factor management Warfarin

Warfarin