The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the mental, physical and social problems associated with loneliness and isolation, but loneliness has long been a serious public health problem in Australia.

According to the 2018 Australian Loneliness Report, produced by the Australian Psychological Society (APS) and Swinburne University, as many as 1 in 4 Australian adults surveyed reported feeling lonely. The finding led APS President Ros Knight to describe loneliness as a ‘psychological epidemic’ in Australia.

‘We recognise it’s not just a mental health issue, it’s also a community health issue and a physical issue. It’s a multidiscipline problem, and we need to make sure it remains on the agenda for every government department, as solutions that are often outside of the health domain,’ she says.

Enforced isolation due to the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly increased the level of loneliness in Australia.

While loneliness and isolation are not the same thing, they reinforce each other. Loneliness refers to the subjective experience of a lack of quality relationships, while isolation is the objective experience of being physically cut off from others. Those who are lonely are more likely to self-isolate, and those who are isolated are more likely to develop feelings of loneliness.

In April this year, an Australian Bureau of Statistics survey found 57% of respondents reported feeling lonely and isolated more often since the outbreak of COVID-19.2

Lifeline has reported an unprecedented number of calls relating to loneliness and isolation, answering more than 250,000 calls between March and May this year.3

Patients with chronic illness or those with disabilities have been particularly affected by isolation this year. Professor Alan Petersen, who studies the use of digital media for engagement among people with chronic illnesses, says issues of loneliness and isolation have come up frequently during his research.

‘Patient experiences are quite diverse at the onset of a chronic illness. It disrupts their sense of continuity.

‘They often have severe ongoing pain and stigma related to their condition, and these things are experienced as very isolating,’ he says. ‘COVID has reinforced people’s vulnerabilities.’

A survey by People with Disability Australia (PWDA) found nearly 90% of members thought their COVID experience of lockdown was very isolating. Many reported no contact with anyone.4

PWDA spokesperson Ms El Gibbs says poverty, lack of accessibility and poor digital infrastructure and literacy all contributed to the level of loneliness among people with disability. Supports were withdrawn almost overnight and services that normally helped people connect with the outside world, such as transport, were no longer accessible. ‘Some felt they were left to die at home by themselves,’ Ms Gibbs says.

| PRACTICAL OPTIONS |

|

For more information visit www.thekindnesspandemic.org.

Health consequences of loneliness

Early in the pandemic, Ms Kim Wallis, a GP pharmacist and consultant pharmacist in Bunbury, Western Australia, spent hours searching GP records for patients at high risk so they could be followed up with wellbeing calls. She then did a more direct search to identify patients aged over 75 at high risk of COVID-19 and also of mental health conditions.

‘Mostly it was just about saying, “How are you?” – and they were happy just to chat,’ says Ms Wallis, who has completed a mental health first aid course. ‘I genuinely think they were just lonely.’

She says spending time chatting to patients has significantly increased the time required to complete Home Medicines Reviews (HMRs) – to up to 2 hours currently. But Ms Wallis believes it is time well spent.

One of her longest HMRs was with an elderly lady who had been isolated at home with her husband who has dementia, unable to access respite care due to the lockdown. He had become aggressive and was continually falling over.

‘She was just beside herself and ended up leaving him on the ground. She was so frustrated, she just wanted to talk.’ Even though Ms Wallis alerted the GP, the husband was hospitalised a week later after he hit his head.

While feeling lonely from time to time is part of the human condition,5 chronic loneliness has physical as well as mental consequences. A United States study found people who said they were experiencing loneliness, social isolation or who lived alone were about 30% more likely to die than the rest of the population – a rate comparable with obesity or smoking.6

Loneliness is associated with heart attack and stroke,7 sleep problems, cognitive decline and dementia,8 smoking and other risk-taking behaviours, poor diet and physical inactivity.9 Those who are lonely are more likely to visit their GP or the emergency department, to have longer hospital stays or to be readmitted,10 and to enter residential care.11

The Australian Loneliness Report found loneliness is closely associated with social anxiety, especially among younger adults, and leads to less social interaction, poorer psychological wellbeing and poorer quality of life. Another study found loneliness increases the risk of depression and suicide.12

Role of the pharmacist

Brendan Chiew, a 24-year-old pharmacy intern working in Dubbo, NSW, was alarmed when he met a patient with fibrosis of the lungs during a regular 6-monthly HMR in 2018. He discovered the patient had no family living nearby and was planning to spend Christmas alone.

While his urge was to invite the patient to his home, he was worried about overstepping the professional boundary. In the end, he was advised that the best he could do was to check up on the patient with a phone call every 3–4 months.

‘With the COVID situation, the amount of time to do what we normally do has doubled or trebled, so we don’t have the time [to do more],’ he says.

The United Kingdom’s 2018 Strategy for Tackling Loneliness summarises the role of health and other public services as recognising the importance of people’s social wellbeing, and exploring how they can identify, refer and better support those at risk of feeling lonely often.13

Most pharmacists have not additionally undertaken mental health training, but as the first touch point with the health system for many patients, they are in a position to broach the subject of loneliness and resultant mental health issues.

For example, APS President Ms Knight, a clinical psychologist, says pharmacists can ask questions about patients’ eating, sleeping and exercise levels. And while the pharmacist’s role in suicide prevention is still under debate, it is a good idea to know who to call if a patient is clearly flat, disengaged or feeling hopeless.

She says pharmacists should not underestimate the value of taking the time to listen to patients. While it is not possible to fix someone’s loneliness – that is up to the individual – pharmacists can encourage people to reach out to their community, reconnect with friends, or even just walk home the long way.

‘It’s not necessary to spend hours with them – it’s just doing anything you can to make it clear they are still connected somehow,’ she says.

‘Just a simple smile, showing you know their name, can make such a difference.’

PSA Loneliness support services and information

| Lifeline Australia | 13 11 14 lifeline.org.au |

| Red Cross | COVID Connect provides free wellbeing calls during COVID-19 at www.redcross.org.au/covidconnect |

| Beyond Blue | 1300 22 4636 www.beyondblue.org.au |

| Gather my Crew | Technology to help coordinate and roster practical support for people doing it tough at www.gathermycrew.org |

| Men’s Sheds | A safe and friendly environment where men can come together. www.mensshed.org |

| Disability Advocacy Resource Unit | Find a local disability advocate at www.daru.org.au/find-an-advocate |

| The Kindness Pandemic | Online community combatting isolation through small acts of kindness at www.thekindnesspandemic.org |

References

- Lim MH. Australian loneliness report: a survey exploring the loneliness levels of Australians and the impact on their health and wellbeing. 2018. At: https://psychweek.org.au/wp/wpcontent/uploads/2018/11/Psychology-Week-2018-Australian-Loneliness-Report.pdf

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Household Impacts of COVID-19 Survey, 29 Apr – 4 May 2020 (No.4940.0). 2020. At: www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people-and-communities/household-impacts-covid-19-survey/latest-release

- Aubusson K. Suicide support service given funding boost amid deluge of calls. Sydney Morning Herald. 2020. smh.com.au/national/suicide-support-service-given-funding-boost-amid-deluge-of-calls-20200609-p550xt.html

- People with Disability Australia. Experiences of people with disability during COVID-19. 2020. At: https://pwd.org.au/experiences-of-people-with-disability-during-covid-19-survey-results/

- Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S, Boomsma DI. Evolutionary mechanisms for loneliness. Cogn Emot 2014;28(1):3–21. At: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3855545/

- Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, et al. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci 2015;10(2):227–237. At: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25910392/

- Hakulinen C, Pulkki-Raback L, Virtanen M, et al. Social isolation and loneliness as risk factors for myocardial infarction, stroke and mortality: UK biobank cohort study of 479 054 men and women. Heart 2018;104(18): 1536–1542. At: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29588329/

- Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC. Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends Cogn Sci 2009;13(10):447–454. At: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2752489/

- Shankar A, McMunn A, Banks J, et al. Loneliness, social isolation, and behavioral and biological health indicators in older adults. Health Psychol 2011;30(4):377–385. At: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21534675/

- Valtorta NK, Moore DC, Barron L, et al. Older adults’ social relationships and health care utilization: a systematic review. Am J Public Health 2018;108(4):e1–e10. At: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29470115/

- Cabinet Office (UK). Social Finance Social Impact Bonds. Investing to tackle loneliness – a discussion paper. 2015. At: socialfinance.org.uk/resources/publications/investing-tackle-loneliness-discussion-paper

- Steptoe A, Owen N, Kunz- Ebrecht SR, et al. Loneliness and neuroendocrine, cardiovascular, and inflammatory stress responses in middle-aged men and women. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2004;29(5):593–611. At: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15041083/

- UK Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport. A connected society; A strategy for tackling loneliness. 2018. At: www.gov.uk/government/publications/a-connected-society-a-strategy-for-tackling-loneliness

‘We’re increasingly seeing incidents where alert fatigue has been identified as a contributing factor. It’s not that there wasn’t an alert in place, but that it was lost among the other alerts the clinician saw,’ Prof Baysari says.

‘We’re increasingly seeing incidents where alert fatigue has been identified as a contributing factor. It’s not that there wasn’t an alert in place, but that it was lost among the other alerts the clinician saw,’ Prof Baysari says.

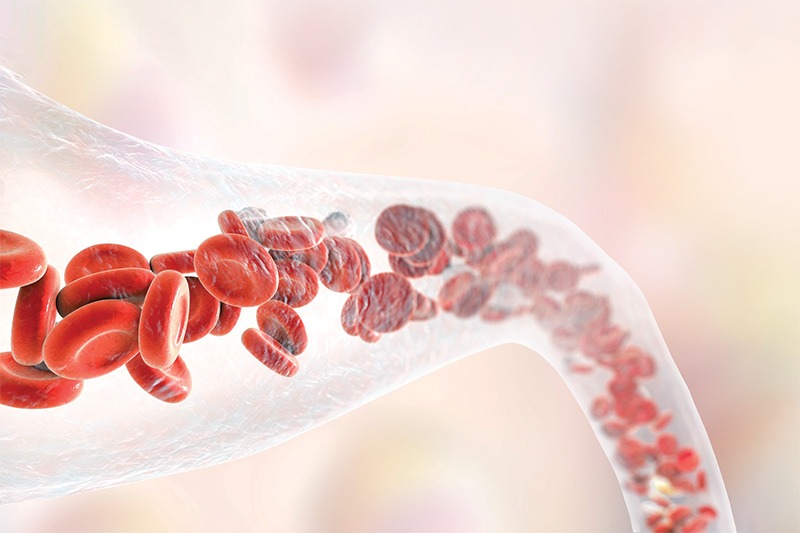

Beyond the arrhythmia, AF often signals broader pathological processes that impair cardiac function and reduce quality of life and life expectancy.5 Many of these conditions are closely linked to social determinants of health, disproportionately affecting populations with socioeconomic disadvantage. Effective AF management requires addressing both the arrhythmia and its underlying contributors.4

Beyond the arrhythmia, AF often signals broader pathological processes that impair cardiac function and reduce quality of life and life expectancy.5 Many of these conditions are closely linked to social determinants of health, disproportionately affecting populations with socioeconomic disadvantage. Effective AF management requires addressing both the arrhythmia and its underlying contributors.4  C – Comorbidity and risk factor management

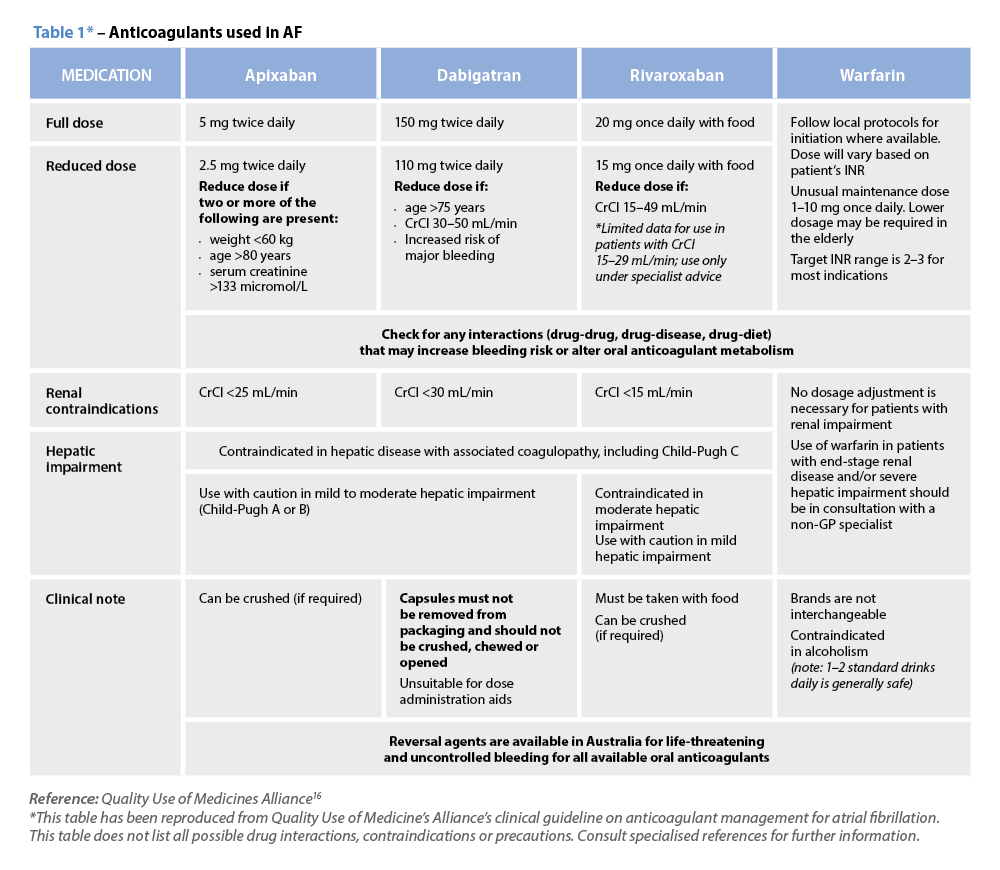

C – Comorbidity and risk factor management Warfarin

Warfarin