Have you ever fantasised about upping sticks and moving to the country? That’s exactly what community pharmacist Taren Gill FPS did, packing up her life in inner Sydney at 23 years old to move to Orange in the NSW Central Tablelands.

Now, she’s a pharmacy owner in Maryborough, Victoria, where she provides personalised, expert care to a population of about 8,000 people.

In this episode of Pharmacy & Me, Taren speaks with hosts Peter Guthrey and Hannah Knowles about the immense rewards of rural pharmacy, talking medicine safety while rounding up sheep and her top tips for other pharmacists thinking of taking up opportunities in rural and regional locations.

Listen to the episode below or find it on Spotify, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts.

“If you became a pharmacist to help people, you’ve got to go to where they need the most help and that’s in rural communities.”

Taren Gill MPS

Follow the timestamps to jump to the topics below:

- [00:05:25] Taren’s career journey

- [00:11:15] Diversity in a small town

- [00:15:39] Transitions of care in the country

- [00:24:00] COVID-19 vaccine rollout

- [00:29:12] Importance of mentors

- [00:32:00] Top tips

Resources:

- PSA’s Medicine safety: rural and remote care report www.psa.org.au/advocacy/working-for-our-profession/medicine-safety/medicine-safety-rural-and-remote-care/

- PSA’s Early Career Pharmacist White Paper my.psa.org.au/s/article/Early-Career-Pharmacist-White-Paper

- Communities of Speciality Interest www.psa.org.au/csi/

- The Wife Drought by Annabel Crabb www.penguin.com.au/books/the-wife-drought-9780857984289

Pharmacy & Me is produced by the Pharmaceutical Society of Australia.

Taren If you became a pharmacist to help people, you have to go where they need the most help, and that’s in rural communities.

Peter [00:00:09] From the Pharmaceutical Society of Australia, hello and welcome to Pharmacy and Me, the podcast that explores how pharmacists do the extraordinary things they do. I’m Peter Guthrey from PSA and a community pharmacist at 24/7 Pharmacy in Melbourne.

Hannah [00:00:25] I’m Hannah Knowles, a Senior Pharmacist at the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital. Each episode, we speak to an everyday pharmacist doing outstanding work about the highs and lows of their career, and we unpack what they’ve learnt and how you can put their experience into your practice.

Today we’re discussing one of my favourite topics: rural and regional practice.

Peter [00:00:45] Practising outside of metropolitan centres may seem scary to some pharmacists. It may involve moving away from established support and networks. However, for those that make the leap, it can be extremely rewarding.

Both Hannah and I grew up in regional New South Wales, studied in regional New South Wales and worked in community pharmacies as pharmacy students. While we both now practise in cities, I know I reflect on my experiences in rural pharmacy often.

Our guest today has shifted in the other direction, leaving Sydney to forge a career in rural and regional Australia.

Hannah [00:01:17] Taren Gill is the owner of Priceline Pharmacy Maryborough, around two hours from Melbourne. She was PSA’s first ECP Board Birector and was recently conferred as a fellow. Congratulations, Taren and thanks so much for coming on.

Taren [00:01:31] Thanks for having me, Hannah and Peter.

Peter [00:01:33] Taren, to start off, for those that don’t know, tell us a bit about yourself. Who are you and what do you do?

Taren [00:01:40] Currently, I am a partner in Priceline Pharmacy Maryborough. We’re a town in Victoria, don’t get us confused with the Queensland one. We get that confusion sometimes with people ordering pizzas to the wrong one, or ordering scripts from the wrong one, but we’re about two hours from Melbourne.

I grew up in Darwin, was born in Darwin, went to university in Sydney. I was an intern on the corner of Hunter and Pitt Street, CBD Sydney and I actually did my intern year in a compounding pharmacy, which didn’t really have complex chronic disease state management. It really didn’t require me to use my expertise and health literacy and communication to translate to a cohort of people who really needed my help, because they haven’t ‘doctor googled’ me before coming in and are basically trying to tell me about the medicine.

So I guess at that time there was what was perceived as an oversupply of pharmacists in Australia, but really it was a maldistribution. That maldistribution was that they weren’t in the countryside. I was a little whippersnapper, a 23-year old newly registered pharmacist looking for work and I couldn’t find any in the city. Thinking of my Darwin roots, I looked at an opportunity in Orange in New South Wales, and it was the best thing I could have possibly done.

I got to wear a few hats while I was there. I was Deputy Director at the Orange Base Hospital, so I got to have a look at that kind of pharmacy.

Peter [00:03:00] How old were you at the time?

Taren [00:03:02] I would say I was around 28.

Peter [00:03:04] That’s an amazing position for someone so young.

Taren [00:03:07] Yes, I think 23 is when I moved. I managed a couple of pharmacies there, looked after 500 beds of aged care, and actually I got the opportunity to lecture at Charles Sturt University. I think country universities just produce ace pharmacists with great communication skills.

Hannah [00:04:27] Just a shoutout, Taren was my lecturer and I can confirm she is fantastic.

Taren [00:03:31] Thanks, I think I’m talking to two CSU graduates here at the moment, and high quality is what you get out of CSU. So I did that job in the hospital, I also got to have a little bit of a stint in a corporate position where I got to look after a group of pharmacies as far as the dispensary operations and their recruitment.

I got to wear a few hats but I guess my passion really still lay in communities with poor access. And also, I really wanted to lead my own team and I felt a little bit stifled by the hierarchy of public health and the fact that I put in some business cases for, say, hospital in the home pharmacists and they got rejected. And they weren’t rejected on merit or on the fact that it was a good business case. It was rejected on the politics of the time.

So I thought, why not give it a crack myself? I got an opportunity through networking. The other great thing about being a rural pharmacist is that you probably go to that little extra effort to attend conferences because you’re a little bit far and removed and sometimes there’s even funding to do so. So that’s another thing I like to do is to get to conferences and meet people and meet students and meet older pharmacists, steal all their wisdom – why reinvent the wheel?

Hannah [00:04:44] Taren, do you have a favourite conference you’ve been to?

Taren [00:04:45] Well, I love them all, but the PSA conference is a lot of fun. And FIP conference, which I went to with Peter, actually, in Buenos Aires in Argentina, was great fun.

Peter [00:04:58] Ah, tangos.

Taren [00:05:01] With rural, I took this opportunity in a town that’s only 8,000 people, and have been here for four years now. And I think you really want to go to where, if you became a pharmacist to help people, you’ve got to go to where they need the most help and that is in rural communities.

Peter [00:05:15] That’s a brilliant quote, that might nearly make the front of the show! In terms of why Orange, you’re in a city of five million people and you have the rest of Australia to explore for opportunities. What drew you into Orange?

Taren [00:05:25] So it was a job opportunity, so it was a pharmacist in charge opportunity. The remuneration was quite good. They actually paid my rent for a year. It was really good. The remuneration was something I couldn’t get in the city, which I think still stands today. I still think country pharmacies pay, if I think of my staff pharmacists, they’re getting paid what I got paid as a PIC back in the day and they certainly don’t have all those responsibilities because they work with the owners.

So, A, the opportunity was there. B, one of the pharmacists in the group that I was going to work for gave me the promise of mentorship, which he followed through on. And then as a young person, I was never going to be able to enter the Sydney market as far as buying a house or any of those things. And where I’d done my intern year, I didn’t really feel professionally satisfied. I’m a medicines expert, and I really wasn’t speaking to a cohort of people that wanted to hear what I necessarily had to say about medicines or to help them with their disease state monitoring. In Orange, they wanted to hear what I had to say.

Hannah [00:06:32] I couldn’t agree more, and my experience with community pharmacy in rural areas is that because there’s such a need, you have a lot of gaps that you can fill. Was there a particular experience that made you think, ‘yes, rural pharmacy is for me’? I imagine you came out of the city as a temporary thing.

Taren [00:06:50] Yes, I came on a two-year contract and that was it. I ended up having two babies in the town, living on five acres with sheep and so forth. We all know that pharmacists are the most trusted profession. We are always coming up in that top three of trusted professions and I think that is magnified in the country.

I feel very accountable to my community and responsible for them. And I think that shines through. As a younger pharmacist, I was in a larger community. Orange has 40,000 people and our town now has 8,000 people. And so you still had access to nice restaurants and since I left Orange has become the food and wine basket of New South Wales (probably because I was hyping it up when I was there, let’s be honest). But there was still enough to do. And I think most country towns do that. I remember ringing up all the other pharmacies in town and saying, ‘Hi, my name is Taren, the new pharmacist’ and another pharmacist from another pharmacy called me back and said, ‘Look, the Canobolas Hotel does a trivia on a Wednesday night. Would you like to meet there?’ And so I think that was a friendly approach. My husband was playing indoor futsal, or twilight soccer, and we were going to do trivia and there was always some event on. And then you can make friends with other young professionals who are finding their feet. So as a young person that was very appealing.

At the age that I’ve moved to this town with two young children, for me it was more like, is there a good playground? Is there one or two coffee shops with great coffee? Will I get childcare access? How affordable is housing? That was just what was on my radar at the time.

Peter [00:08:32] And you’ve mastered the art of going from one sort of fine food and wine district to the other. I can speak from firsthand experience that the food and wine culture in Ballarat is quite outstanding.

Taren [00:08:38] And we have the Pyrenees Wine Region just here at Avoca where I have my depot, one of the last depots in the country.

Peter [00:08:47] In terms of the depot, how does that actually work?

Taren [00:08:49] There’s a grandfather clause, even though there’s a pharmacy in the town of Avoca now, because our depot existed before, it doesn’t need to close. So basically, we service Avoca Nursing Home and we have our depot where people can shop there, drop their prescriptions in and we dispense prescriptions and have them delivered out on the same day. And then we provide counselling over the phone. So that’s another good service for that town, and obviously being able to service the aged care facility in a town that’s a 30-minute drive away is pretty special.

Peter [00:09:19] You said that you need to go to where the problem is and where the health needs are the greatest, and certainly PSA’s Medicine Safety Report this year has highlighted the quite astounding disease burden in rural and remote Australia. But even motivated by that, big decisions do often lead to self-doubt or at least nervousness, and they’re big moves away from traditional support structures. Did you have to grapple with that at the time you made those decisions to move?

Taren [00:09:41] Yes, totally. I come from a very close family and I had just gotten married, and my husband is from a big Punjabi Sikh Indian family, and even telling them that we wanted to be anywhere away from them was just huge.

Peter [00:09:55] How did they react?

Taren [00:09:56] They weren’t happy, my in-laws were certainly not happy that I was taking their son away from them. A very Indian-type thing, especially being an Indian, I guess, many cultures are quite patriarchal and here I am the wife saying off we go for my opportunity. But once we had settled in a little bit, I think my in-laws, and obviously my parents, were very supportive of what we were trying to achieve. They could see that we were making a life for ourselves and were able to do it. But I think another thing, when I speak to people that’s a big consideration is what can my partner do? So depending on what your partner’s job is or if you have a partner, or you don’t have a partner or you feel like you don’t have opportunities to meet a partner, if you go to a smaller town or there’s less social interactions, I know that is something I discuss with early career pharmacists a lot. And certainly when I recruit and I find out someone has a partner, that’s part of my recruitment. I’m like, what do you mean your partner is an accountant? I can find them a job. I’ll start talking to my network in town, I’ll get you a job. You’re a truck driver, you’re a plumber – my last recruit of an intern was gold for my town because she was an intern pharmacist and her partner was a GP, and I was like, we’re getting a GP and a pharmacist! It was really great.

Hannah [00:11:11] Did you get knighted or given the keys to the city?

Taren [00:11:15] Yes and I guess that’s probably a good segue to country towns around diversity for me, because my intern and her partner are a same sex couple. And I feel like, in our town, that is very well received. I have been asked by students at student conferences about diversity in rural towns and certainly my experience hasn’t been anything other than positive. You’re going to have people with their views anywhere in the world, that doesn’t make a country any different. But I think because we are smaller and we get to know each other better and we’re not judging books by their cover or whatever else you want to judge a book by, that’s been really great.

Hannah [00:11:56] Absolutely. I found my experience in country towns as often the people that were first a little bit wary become your biggest advocates when you settle into the community and develop all those connections.

Taren [00:12:08] This is the thing. Something that irks a country town is the transient nature of its professionals. If you’re going to come in as a professional and you’re going to lay some roots like, say, I’m sending my kids to school here and I’ll see you at soccer. Or I’m not just here until I get my visa requirements and then I’m back off to the big smoke, which unfortunately a lot of our overseas-trained doctors do. If you show some level of commitment, it really doesn’t matter who you are, what you look like and what you sound like, you’re going to be embraced by the community, I think. And that’s certainly been our experience. I come from a Sikh family, my husband has a turban and beard, so my son is the only little boy with a turban at our public school. Looking different is our superpower. Can I hide from any customer at Woollies? No, they know me, they know my kids, there’s no hiding. There’s nothing to hide, but certainly if you want to have a quiet moment where you’re shoving your trolley with really bad food, there’s just no opportunity – they’re going to look in there.

Peter [00:13:05] Do they bug you for questions about all their ailments in the aisle as well? Do you get what doctor’s experience, which is like, solve my problems for me?

Taren [00:13:8] Totally. About prescriptions or can you look at this rash or anything like that. So yes, I think, on diversity, I think the transient nature of people is what – and look, don’t get me wrong, that shouldn’t deter someone from dipping their toe for a locum or six months or a year. But I don’t think judge the community’s reaction when you say, oh, well, I’m off now, see you later. Because they really want to see you, they really want to know how your kids are going, they want to know all those things. Particularly being an HMMR pharmacist, a Home Medicines Review consultant pharmacist, I get the privilege of entering people’s homes, and those homes could be properties where I’m conducting the interview while they’re feeding their alpacas, with animals all over the place, you know, helping them put their sheep back into yards while I’m talking to them becauseI think pharmacy is so important, but actually that’s just one part of everyone else’s day. Just like to the shops or going to the dentist or whatever else. For me, it’s eight, nine hours a day and for them, it’s like they’re just trying to fit me in.

Hannah [00:14:15] Taren, with that, do you have any tips for people with lower health literacy and who potentially don’t have health as such a high priority?

Taren [00:14:22] Yes, I think stories are really, really important. For example, with compliance, I will often tell my patients the story of, so I’ve got high blood pressure, big deal, what does it mean? So I tell the story, imagine if you’ve got these pipes and you’ve got water rushing high in them all the time, and you get wear and tear and then you get some scum inside the pipes. And normally, it’s like an older man who’s been working on his farm for hours and I’m talking to him and I say, all that scum inside of it, that’s like your cholesterol plaques and everything’s narrowed, and now it’s going faster. And what if you get like a pebble or something in there and it just gets stuck somewhere and that’s your blood clot. And all these tablets I’m telling you about on their own, they don’t, yes, you’re right, who cares about a bit of high blood pressure, this or that? But all together, we’re trying to stop a stroke, heart attack, pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis. So the big picture. When I sort of explain the parts of it, compliance becomes better because before it, it would be like, oh, I missed that, she’ll be right. And now it’s like, oh, okay, Taren said if I take my aspirin and my rosuvastatin and my ramipril and da da da da da, then maybe it tells a bigger story and a bigger picture.

Hannah [00:15:39] Taren, you’ve mentioned the risk of compliance in rural communities, another area that I’ve had experience with is the transitions of care post-hospital. So I’m currently in a major tertiary hospital in Brisbane, and we have people transfer from the regions for all sorts of conditions, and I was on the cardiology ward looking at transferring people home on six or eight new medications post a STEMI. How does your role as a community pharmacist help with aiding those transitions of care?

Taren [00:16:08] Yes, so a very big topic, ruraly, transitions of care. And there is hospital but there’s also inter-aged care or back into the home. So there are lots of points of vulnerability where medication misadventure can happen. I think the biggest issues we have is, firstly, you have to remember rural patients are travelling distances, they’re not just going 20 minutes out of the hospital to their home, where the community pharmacy is probably open until nine o’clock at night and can probably do that Webster-pak that night, that probably keeps that really obscure oncology drug on hand and doesn’t need to order it in.

So I think we need a greater understanding of those challenges. Don’t get me wrong, transitions of care challenges happen in metro areas as well, but I think that it would be good if there was a greater understanding at tertiary or metro hospitals, or even for us at Ballarat or Bendigo base hospitals, about the challenges. Some of my patients are taking taxis to get home. So there’s already the added costs involved, so they are taking a taxi to travel 80, 90 kilometres to get home, then their first stop is the pharmacy. I may not even know about their discharge. I may not have their medicines on hand. I may not have a complete picture of what’s going on and there’s a delay in treatment. And I think that’s the biggest problem because what happens when we get it wrong on discharge, they become frequent flyers and bump straight back into hospital.

What I did enjoy when I worked at Orange Base Hospital and having that community background was when I did discharge, I knew absolutely everything that pharmacists needed to succeed when that patient or that family member walked in the door. And I just so wanted that community pharmacist to succeed in that moment because when everyone goes home at five o’clock or whatever time the shift ends in a hospital, that community pharmacist is there just trying to put the pieces together and paint a picture and do the right thing by that patient. And I think we are just getting this widening of the gap between city versus country when it comes to health care, when it comes to that access. It can take six weeks to see a GP in our town. And so on a weekend, it’s just me and a nurse practitioner looking after the town. So I’m saying, someone comes in and says look at this rash, I think it’s shingles, I call the nurse practitioner and say, ‘Can you please write me a prescription for valacyclovir?’ And then I’ll dispense it, and there’s actually no doctor involvement. That’s not ideal for the patient, is it? What if I was wrong? I’m not a doctor; it’s not in my scope. So I really do think that we’re getting that widening of the gap. And I guess there’s a brain drain in the country as well, and so we’re not getting our, the cream of the crop is probably not choosing to come to our rural towns as far as prescribers and in sometimes as far as our own pharmacist friends, because clever pharmacists want to work at tertiary hospitals. But I get it, different people want to do different things, but community pharmacists are very much so clinical pharmacists. You are as clinical as you want to be and I think sometimes there is that perception that people might not get a clinical experience in a community or a rural pharmacy. And then therefore we’re not getting the cream of the crop to come and help the people who need the most help.

Peter [00:19:10] You mentioned that the workforce challenges are getting worse and worse with time, and the data backs up your experience as an owner. PSA’s Medicine safety: rural and remote care report this year found that in the next couple of years, we’re going to actually see a widening of that gap and that we will have, for every 100,000 people in the city, there’ll be 113 pharmacists and in the country that’s only 52. So there’s already less people in the country, and there are bigger distances and there are bigger distances going to be separating that care and support. But from what you’ve said, rural pharmacy can be such a wonderfully clinically enriching experience. What are some of the most astonishing interactions you’ve picked up or the most amazing episodes of care that you’ve had to help patients?

Taren [00:19:57] There are so many examples, actually. I have a clozapine patient who travels quite a distance to access us, and he’s just so grateful at every interaction that we are able to help him manage his disease state. Because there was a time in his life where it was really, really bad. When his bloods went amber and I was like, we’re going to have to go week to week, he was just so anxious and being able to sit down and talk to him about that. Because we have a team, where such that if a pharmacist needs to go into a consult room or spend some extra time to do that meds check or immunise or whatever, we can leave the dispensary bench to do that.

I’d like to think that our team and many rural pharmacy teams provide a judgment-free environment. The whole town shops in the one place. Unlike the city, where I guess different suburbs have socioeconomic differences and a pharmacy in a certain suburb might get one cohort of people in a pharmacy and another in a different class of suburb. Whether you’re driving a Mercedes or you came in on a taxi, you’re all shopping at the same Woolies, the same Kmart and the same pharmacies. So you’re really seeing that whole spectrum of humans, and everyone needs help at some point. Everyone has a sick baby with a fever at some point. Everyone needs an immunisation at some point. Everyone needs an antibiotic or obviously a lot of people have chronic disease states as well.

Hannah [00:21:15] So Taren, we touched on rural shortages before of pharmacists, and I know a lot of other health professions are feeling the burden and the pinch of that as well. You’ve articulated that comes with the challenges of not having GPs on the weekend. Does it also come with opportunities for pharmacists being involved in people’s health care?

Taren [00:21:35] Yes, definitely. I do worry for my team and even my own burnout. We’ve certainly seen that during the pandemic. So I’ve worked six days a week for the last 18 months without a break basically, and big hours, and to answer your question about opportunities, there is no turf war in our town. There are enough sick people for all of us. The doctors know that, we know that, the nurse practitioners know that, everyone knows it. So for example, I remember with, you know, leave consultations, oh turf war, no, my doctors are great. Someone goes up there and says they’re, the receptionist literally says, go down to Priceline Pharmacy and see Taren, and she will sort you out. So there’s no turf war on leave consultations, there’s no turf war on immunisation. Doctors couldn’t be happier that we’re getting Moderna and they’re not. They’re just like, whew. And when we get the opportunity to do case conference, it’s really quite collaborative. And I guess the other thing that’s kind of cool is normally in community pharmacy, you’re probably not referring straight into the diabetes educators or straight into social workers and things like that.

Peter [00:22:40] What would really help you do more for your community? Pharmacist prescribing is certainly something that we identified in that report, and it’s something that there’s a really great feature on in the October Australian Pharmacist Journal, but what would help you do more for your community?

Taren [00:22:53] I think having the funding to be part of more case conferences as a community pharmacist, rather than having to rely on funding from a meds check or HMR and the referral process and all of that coming out of the 7CPA pot of money. I think there needs to be some funding because we do it anyway. And I laugh when people say, aren’t you worried about pharmacists in GP surgeries in a rural town? I can get a pharmacist in the pharmacy, they can’t get GPs in a GP surgery. But there does need to be a remuneration mechanism that allows for that.

For example, the Royal Commission into Mental Health only had one site for rural consultation in Victoria and it was actually the town of Maryborough. And so that was really interesting to be a part of as well and just to think of, and again, amplified by the pandemic, the mental health issues that are happening across so many age groups. People are going to need us for so many more years. This is not a short-term thing. They don’t just need a few pharmacists and the GPs just for now. They’re going to need us for a long time.

Peter [00:24:00] I remember at a PSA conference many years ago there was a wise line from the panel that said there’s plenty of medicine safety problems to go around. It’s not a turf war, we’re never going to solve all the medicine safety problems. A few months ago, Taren, both of us were on ABC Radio Victoria’s Conversation Hour, which was a lot of fun, but I was really quite taken with how passionate you were about some of the issues you’ve spoken about today, but also how keen you were to get involved in the COVID-19 vaccine strategy. I know at the time of taping today you’re still waiting for the Moderna vaccine, but what’s your experience been like so far being involved in the program?

Taren [00:24:35] The second that our pharmacy received AstraZeneca stock, the town was just so excited because we decided to go the no barriers walk-in method. They could book online through the Priceline website if they wished, but we just went, look, we’re going to do walk-ins. We really decluttered and uncomplicated the process.

So yes, I think immunisation has certainly been a big thing for us. People still come to us to get their Boostrix even though they could get it for free from community health because they just know how accessible we are. It could be a case, of my husband works all week and I can only come in on a Sunday. I’ll say, you know, there is a small fee with us because it’s not through the NIP, not through a community health centre, and they are happy to pay. So immunisation has been a very exciting expanded scope of practice for pharmacists, which I think with booster shots and all that will get even bigger. But it’s all around access, isn’t it? There’s no getting through anyone to get to us. There’s no receptionist. They can see me; they know when I’m eating, for God’s sake. Oh, Taren, we caught you eating. They don’t give you two seconds, they’ll keep talking.

Peter [00:25:37] I think all pharmacists can identify with that stolen lunch break in one way or the other. I think one of the things, in taking a little of a step back, we’ve spoken that you’ve got this amazing hospital management experience, you’ve got community pharmacy management experience, you’ve been a uni lecturer, and we’ll talk a bit more about you being on the PSA Board in a second. How did all of those quite different roles set you up to be a really good community pharmacy owner that is doing amazing things to help a community that previously may not have had that level of service?

Taren [00:26:04] Yes, so I think it’s probably around my constructive discontent. Don’t confuse that with destructive discontent, because I have that sometimes with my kids. But yes, I think around constructive discontent, I mean, I don’t mean to quote Kanye, but can it be better, faster, stronger? And I think that’s certainly how I got that ECP Board Director position, to be honest. I just was feeling very dissatisfied with lots of aspects of pharmacy and didn’t really apply to get it, applied to be able to have a say on what I thought to the President and the CEO of the time. And that became, you know, a couple of years appointment and where I continued to, and continue to this day on the PSA Vic Branch Committee, to sort of try and speak up for the parts of the profession, which, let’s be frank, is a bit male, pale and stale at times. When we talk about 70% of us are female, it’s multicultural, maybe part-time workforce because we are parents and a young cohort of people, which I don’t fall in anymore. But that’s okay, maybe I’ve got wisdom. I’m not sure, I’m still working on it. So yes, I think constructive discontent. I’d really like things to be better in a more constructive way, because where there is capacity, we should try. And I think that’s where it comes from. I love being a pharmacist. There are days where I haven’t had a great day, but at no point have I ever not loved being a pharmacist or pharmacy itself and just everything that pharmacy stands for: reliability, you know, we are accountable for what we do, and we help out when we can.

Hannah [00:27:44] Definitely, and I’m sure you’ve made a massive impact on your patients in Maryborough. With being the first Early Career Pharmacist Board Director, what did you expect going into the role and then how do you think having you in the room has helped PSA achieve some of the things that we’ve seen in the past few years?

Taren [00:28:03] So I hadn’t really had a huge governance role before, other than some committees on medication safety and things like that in the hospital. So I went in keen to learn a lot from those who already sat on the board, and there were ex-Presidents of both the Guild and PSA on that board at the time. What I think came out of it that’s really exciting was the ECP white paper. It started out with a consultation with NAPSA at the NAPSA Congress and went around the country talking to different pharmacists, trying to get their viewpoints. And I say to pharmacists, even till today, have you ever looked at the ECP white paper? Print it out and hand it to your boss, your Director of Pharmacy, print it out and hand it over to them and say, as a young person, I identify with some of these challenges in here. We’re trying to come up with solutions for ourselves, but it would be good to work for it together. I think an early career pharmacist has the most to lose. We’re in the workforce for the next 30 to 40 years, we want to do a good job, but we have other challenges – and the pandemic, obviously.

Hannah [00:29:12] Taren, you’ve done some amazing things throughout your career, and we’ve been lucky enough to discuss some of it today. How has having mentors and being a mentor shaped that pathway?

Taren [00:29:20] In a massive, massive way. I had some really great, and still have some really great, mentors that helped me get to where I am today. Particularly, I think when emotion is high, intelligence is low, and I certainly experience that because I’m a pretty passionate person who wears my heart on my sleeve. It’s been really good to be able to bounce ideas off, particularly when I’m feeling very emotional to pharmacists and people outside of pharmacy too, who can give me guidance on my communication skills, on how I would like to lead a team. And going outside of pharmacy and just watching Simon Sinek or Brené Brown, people like that, understanding our vulnerability. And then wanting to pass that on to my interns and early career pharmacists, retail managers and other staff members to get good culture. Culture trumps strategy every single time. I can write a million strategy documents, and when my team hasn’t got the right people in the right seat of the bus, we don’t succeed. So yes, definitely, I think mentorship is important. If you don’t have a mentor, I understand that PSA has programs to help you get mentors. And if you want to come to Maryborough, I’m happy to be anyone’s mentor.

Peter [00:30:28] Back on the topic of conferences, the people you catch up with at the meal breaks and you start with social chit chat may well become those mentors and you bounce off them in the future. On the topic of mentorship, though, we have a few questions towards the end that we like to ask all of our guests – what’s the best piece of advice that’s been given to you and helped you in your career so far?

Taren [00:30:47] The best piece of advice is probably ‘fake it till you make it’, and I’d like to tell everyone else to did that too. Everyone is like, Taren, you are so confident, and in my head I’m like, I am definitely winging this but I’ll do it with a smile and see how it lands. I think, particularly women, it’s in that book by Annabel Crabb, Why Women Need Wives and Men Need Lives, they talk about how men will apply for positions they’re not qualified for, and a woman who might be even more so qualified but because they feel that they don’t tick every box, then they don’t put their hat in the ring. And yes, I think that’s a very, you know, that could be a big generalisation. But I’ve seen that in my friends, oh, I can’t do that. Even going for that Deputy Director of Pharmacy position, I went for a Grade 3 New South Wales Health position without ever working in the hospital system. I went in and I said, you’ve asked the question, you’ve talked about acute and subacute, I’m going to talk to you about looking after 500 beds of a nursing home and all the operational, logistical and clinical things around that. Will I be your best emergency pharmacist? Probably not, but I have been triaging my ailments for years. So I think fake it till you make it, talk to your mentors about that and surround yourself with people that are going to build you up, and be there for someone else as well

Peter [00:32:00] And really focus on those transferable skills. I think as you just pointed out, we don’t necessarily consider the clinical work we do in community pharmacy as having a direct transfer to clinical work in hospital pharmacy. And it absolutely does. And finally, what are your top three tips for other pharmacists thinking of taking up opportunities in rural and regional locations?

Taren [00:32:20] Do you need three? I think just do it. That’s my top tip – just do it.

Peter [00:32:25] You can say, ‘do it, do it, do it’.

Taren [00:32:31] I think the pandemic has made people less likely to leave their comfort zone, and I do understand that. Crossing borders and not being able to see your family because the borders are shut down. Wherever you are choosing rurally, will you have great mentorship with the pharmacy, pharmacists, whoever is going to be there? Because I think when you work rurally, it’s not about clocking in and clocking out, leaving. That group of people will be the same people you have dinners with, you go to trivia with, you probably spend the public holiday with at a barbecue. You don’t know if you’re going to get along with them until you give it a go. But do you get a good feel for them? Does it sound like if you are an intern, they’re going to spend their time sitting with you on a Wednesday night studying over dinner? That’s certainly what we try to do here, spend that extra time doing practise exams and taking you to a conference so that you can meet people and see, try to work out your own style, what kind of pharmacist you want to be.

If you have a partner, talking to your partner about what those opportunities might be for them. Remembering that the cost of living rurally is much lower. So if you’re a young person who has aspirations for buying a house, that might be more achievable. And talk to a prospective employer about your partner and say, look, have you got any ideas? Do you know anyone? And chances are the pharmacists in town know someone who can get them a job, that’s not going to be a problem.

I think the third one is don’t discount how much of an impact you’re going to have once you get there. You don’t realise you’re walking in with this status already. When you walk in as a pharmacist, pharmacy intern, pharmacy student, the town’s already like, wow, that’s the pharmacist. And your status is already like, I don’t know whether your status should matter or not, but I think it does feel good. It does feel good to be wanted and liked and acknowledged. Because we’re all humans and that feels good. So I think don’t discount your medicines expertise after your degree. There are people that really want to hear what you have to say, and I feel really disheartened in some of the discussions I see on the PSA ECP Facebook page with some people who are feeling disheartened, because I just can’t imagine that experience in any rural town at all.

After only having one tip of just do it, I now have my fourth and it’s get involved and be part of the solution. So I think at the time when you are feeling disenfranchised and you probably have many opinions and the most to say, that’s the time to get involved. But of course, get involved before that and bring some of your pizzazz as well. But there are so many ways to get involved in our profession, and many of them are through PSA. Being a member, of course, but also getting involved in some of the special interest groups. Maybe start surrounding yourself with likeminded people, who may be able to help build you up or introduce you to new opportunities. But also make sure you have your voice. Don’t wait for anyone else to say what you’re thinking. I think it’s really important to get involved.

Hannah [00:35:21] Taren, thank you very much for coming on the show and sharing all of your experiences. It’s really insightful to be able to discuss some of the things that happen in rural practice and particularly bust some of the myths that there is about the lack of support, lack of opportunities and issues with having partners and jobs. It’s really nice to hear from someone that’s made a few moves to rural areas and is really thriving. So thank you very much.

Taren [00:35:38] Thanks Hannah and Peter, it’s been lovely.

Peter [00:35:50] Thanks, Taren, it’s been an absolute joy. And thank you to everybody for listening. Check out the show notes for links to everything we’ve spoken about today, including more on the startling findings of PSA’s Medicine safety: rural and remote care report. Plus don’t forget to subscribe to hear episodes as soon as they are released.

‘We’re increasingly seeing incidents where alert fatigue has been identified as a contributing factor. It’s not that there wasn’t an alert in place, but that it was lost among the other alerts the clinician saw,’ Prof Baysari says.

‘We’re increasingly seeing incidents where alert fatigue has been identified as a contributing factor. It’s not that there wasn’t an alert in place, but that it was lost among the other alerts the clinician saw,’ Prof Baysari says.

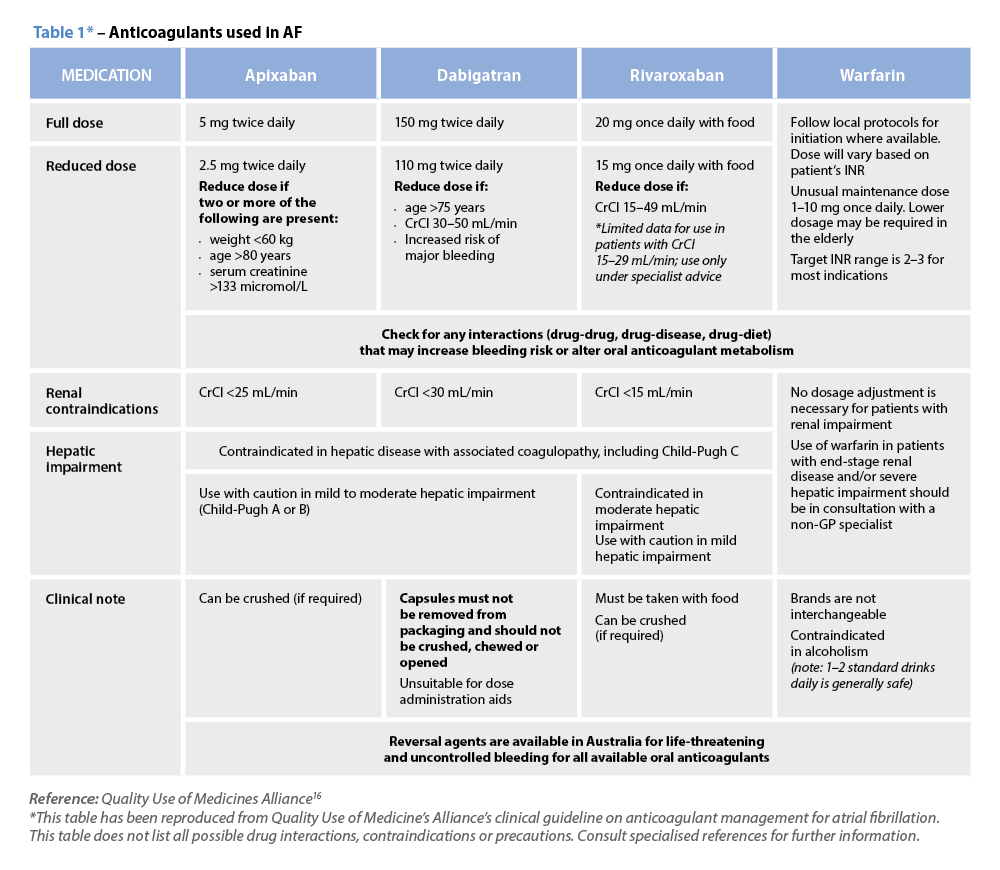

Beyond the arrhythmia, AF often signals broader pathological processes that impair cardiac function and reduce quality of life and life expectancy.5 Many of these conditions are closely linked to social determinants of health, disproportionately affecting populations with socioeconomic disadvantage. Effective AF management requires addressing both the arrhythmia and its underlying contributors.4

Beyond the arrhythmia, AF often signals broader pathological processes that impair cardiac function and reduce quality of life and life expectancy.5 Many of these conditions are closely linked to social determinants of health, disproportionately affecting populations with socioeconomic disadvantage. Effective AF management requires addressing both the arrhythmia and its underlying contributors.4  C – Comorbidity and risk factor management

C – Comorbidity and risk factor management Warfarin

Warfarin