Rather than managing adverse events after the fact, a new data-powered system has been designed to proactively tackle medicine-related problems before they arise.

The Activating pharmacists to reduce medication related problems (ACTMed) stepped wedge trial – co-led by University of Queensland’s Professor Lisa Nissen FPS and Dr Jean Spinks – is set to launch across 42 Queensland-based primary care practices next month, following a successful 6-month pilot at three sites.

The pharmacist-led quality improvement initiative uses an interactive real-time dashboard to alert pharmacists embedded in GP practices about potential medicine safety risks.

But it’s not technology alone that forms the backbone of the system, said Dr Spinks.

But it’s not technology alone that forms the backbone of the system, said Dr Spinks.

‘It’s a really positive way for pharmacists and GPs to collaborate, and for pharmacists to apply their clinical knowledge in a meaningful way,’ she said.

How it works

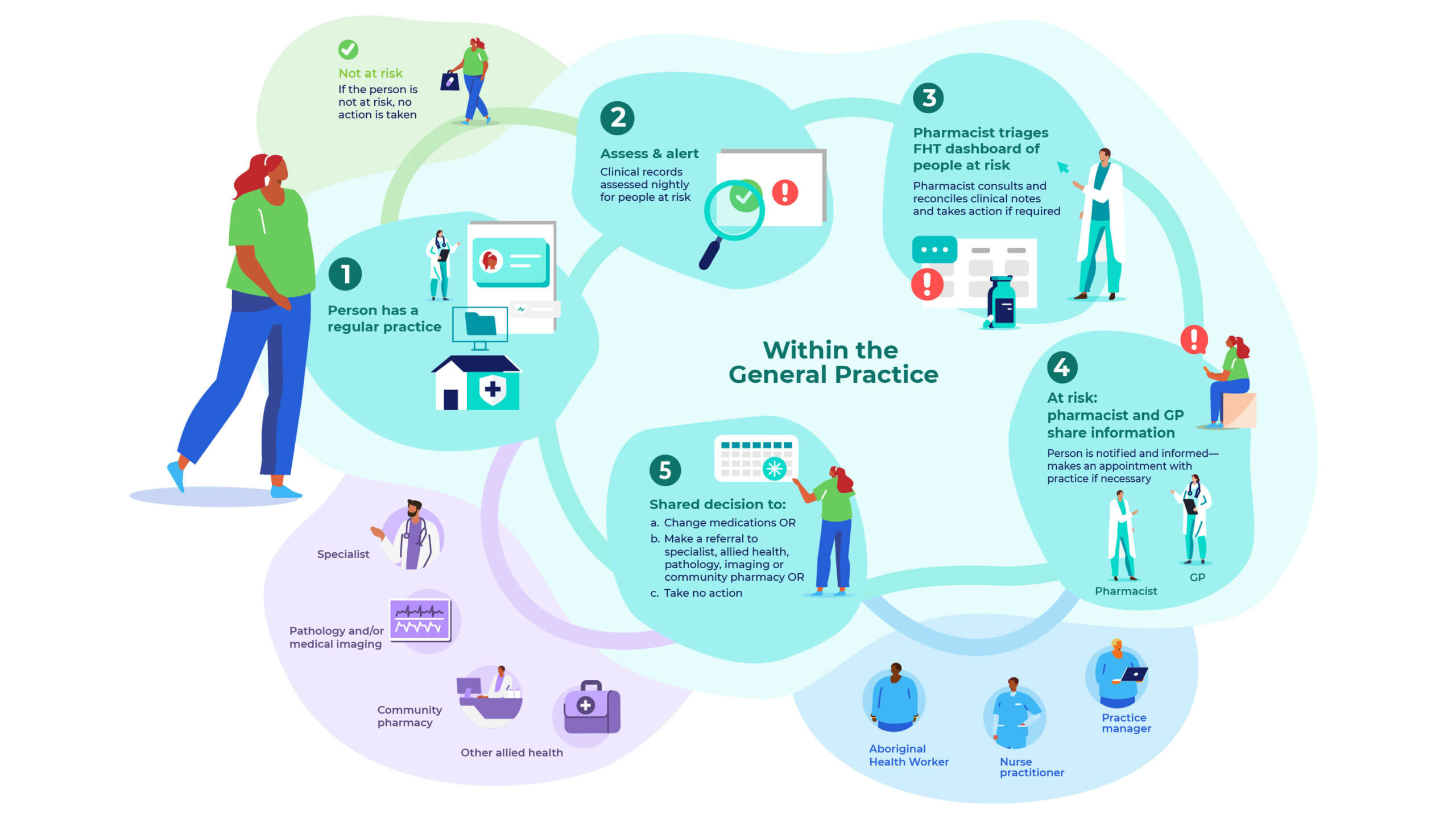

When a GP practice closes its doors for the night, the ACTMed system gets to work. Data-extraction tool GRHANITE™ works in conjunction with decision-support software Future Health Today (FHT) to run patient records through a set of algorithms.

When anyone meets certain criteria flagged in the algorithm, their information comes up into a dashboard for pharmacists to triage, said Dr Spinks.

Clinical indicators for five conditions were built into the software to identify at-risk patients with the following chronic conditions:

- atrial fibrillation

- heart failure

- cardiovascular disease

- type 2 diabetes

- asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

For example, a patient with type 2 diabetes might be flagged in the system if they:

- are taking any medicine to manage their diabetes; and

- haven’t had a haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) test for 6 months.

Not all patients who come up in the system will require an intervention – it’s up to the pharmacist to triage the appropriateness of recommendations across the five disease states. That way, GPs are left with a refined list of patients with potentially pressing problems.

For Dr Aaron Chambers, practice owner of Growlife Medical, the first site to join the pilot, ACTMed was all about good use of data to improve clinical collaboration and patient-centred care.

‘Having a pharmacology expert within the practice who the doctors can chat to about various issues has been really valuable,’ he said.

‘The improved communication between the pharmacist and the GP, particularly when conducting Home Medicines Reviews (HMRs), has been fantastic.’

The ACTMed system also reduces the risk of medicine-related harm for patients who might have otherwise fallen through the cracks.

‘When you’re in the heat of the moment as a GP and you’re prescribing for a patient with multimorbidities or very complex medicines, errors or inadvertent things can occur that result in medication safety risks,’ he said.

‘This is a great way of monitoring things where either a therapy was missed due to lack of review, or a medicine was added that could cause a safety issue that might not have been recognised on a day-to-day basis.’

Designing a collaborative approach

Before the trial commences, each practice needs to set up its own quality improvement cycle and team to manage the process, consisting of at least:

- a pharmacist

- GP

- a practice manager, nurse or Aboriginal health worker.

‘The quality improvement team will then work together to set the goals for the service and how it’s going to operate within the practice,’ said Dr Spinks.

When Burpengary Morayfield Hub Medical Centre joined the ACTMed pilot, the team discussed which clinical indicators to focus on and how at-risk patients should be managed, said practice pharmacist Amy Gibson MPS-AACPA.

‘After looking at patient records, we either held a case conference or conducted a comprehensive medication review for those at the highest risk,’ she said.

This was the case for one patient deemed at cardiovascular risk, who had had a heart attack 4 years prior and took a ‘relaxed’ approach to his health, including non-compliance to medicines.

‘We put him on the case conference list, and I flagged this history with the GP,’ said Ms Gibson.

Within a couple of weeks, she booked the patient in for a medication review to discuss reducing cardiovascular risk and how medicines can prevent a second heart attack. While the patient decided not to go back on a statin, he did agree to take low-dose aspirin.

‘We put that recommendation forward to the GP, who was happy with the outcome,’ she said. ‘It was very much a shared decision-making process between the GP, patient and pharmacist.’

As a general rule of thumb, the practice opted not to issue recalls, due to identified ‘recall fatigue’ among its patients. It was therefore agreed Ms Gibson would phone patients in the next risk category to ask them to come in for an appointment.

‘For the rest of the patients who were flagged, we decided the issues could be discussed in their next appointment,’ she said. ‘The vast majority come into the practice fairly often, so there were plenty of opportunities for the GP to have those discussions.’

Benefits for ACCHOs

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients have higher hospitalisation, morbidity and mortality rates than non-First Nations Australians. So a system that proactively identifies potential medicine-related problems can be hugely beneficial for Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations (ACCHOs) and the communities they serve.

For example, Amanda Sanburg, a pharmacist who works across two ACCHOs, identified several patients with an atrial fibrillation diagnosis through the ACTMed pilot who weren’t taking an oral anticoagulant.

‘One recalled patient was then put on an oral anticoagulant after the doctor checked their previous history,’ she said.

Understanding the community’s wants and needs is also important to how the ACTMed system is applied across ACCHOs.

For example, of the 80 patients who were flagged for not having an HbA1c test within 6 months, only a dozen were recalled.

‘The clinic feels that a lot of our mob aren’t keen on having blood taken and the local laboratory doesn’t have particularly good hours,’ she said. ‘So if their last HbA1c was acceptable, we’ll give them the forms and paperwork to get the test when they next come in.’

ACTMed is also crucial to identifying non-compliant patients, potentially triggering an HMR or further contact with a health worker to encourage them to take their medicines.

‘HMRs are usually conducted at the discretion of the GP or clinical staff, but I can say “I think I need to see this person because they have an HbA1c over 10%, and could benefit from a chat about medicines compliance and diet,’ said Ms Sanburg.

John Jones MPS, pharmacist immuniser and owner of My Community Pharmacy Shortland in Newcastle, NSW[/caption]

John Jones MPS, pharmacist immuniser and owner of My Community Pharmacy Shortland in Newcastle, NSW[/caption]

Debbie Rigby FPS explaining how to correctly use different inhaler devices[/caption]

Debbie Rigby FPS explaining how to correctly use different inhaler devices[/caption]

Professor Sepehr Shakib[/caption]

Professor Sepehr Shakib[/caption]

Lee McLennan MPS[/caption]

Lee McLennan MPS[/caption]

Dr Natalie Soulsby FPS, Adv Prac Pharm[/caption]

Dr Natalie Soulsby FPS, Adv Prac Pharm[/caption]

Joanne Gross MPS[/caption]

Joanne Gross MPS[/caption]