A look at Turlington’s 27‑ingredient balsam, its broad therapeutic claims and how it contrasts with today’s evidence‑based approaches.

Robert Turlington was a 21st Century pharmacist living in the 18th Century. But the Londoner wasn’t always the successful entrepreneur he later became. Instead, Turlington (1697–1766) began his working life as a weaver – and a bankrupt one at that – courtesy of his demanding specialty: silk.1

According to archaeologists Olive Jones and Allen Vegotsky, the ‘multidimensional’ challenges of the silk trade, along with the fallout from bankruptcy, had an unexpected upside. They pushed Turlington to develop skills in marketing, labour organisation and even fashion. This expertise helped him change careers and, in 1740, grow a one-man pharmaceutical operation into an early multinational success story.1

Let sales begin

By 1742, Turlington was selling his Balsam of Life into a market packed with competitors like Friar’s Balsam.2 Both elixirs were sold as treatments for several illnesses and injuries. But in no time, Turlington went beyond ‘several’, pitching his product as a veritable ‘cure-all’.1–5,10

‘The aforesaid Balsam is a certain relief for the gravel, cholic, rheumatism, gout, and sciatic pains, and all colds, coughs, consumptive, pectoral, asthmatical, and nervous disorders, &c. and for any cut, bruise, or the like, as thousands can testify who have been relieved thereby, in the above and other complaints, after every other resource has failed,’ claimed Turlington in a 46-page testimonial pamphlet, accompanying each sale.1

In line with the era’s one-product, multi-ailment ‘polypharmacy’ approach, Turlington’s ‘perfect friend to Nature’ initially contained 27 ingredients in an alcohol solution. Over time, that was reduced to just eight. The key ingredients remained plant-based balsams: gum benzoin, storax and Tolu and Peruvian balsam. Aromatic spices like cinnamon, saffron and nutmeg masked the balsams’ unpleasant taste.1,2,5,6,10

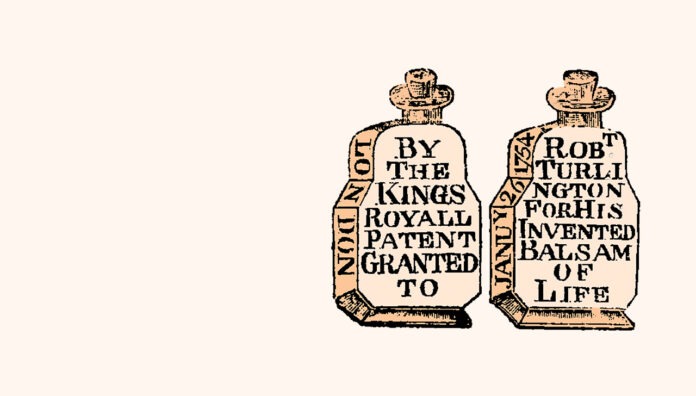

Originally sold in round vials, Turlington’s nostrum became so popular that in 1746 he introduced the first of several distinctively shaped bottles to deter imitators.

In 1754, he followed-up with a unique pear-shaped bottle, which continued to be used in different sizes for over 150 years.1,3,7

They remain collectors’ items to this very day.1,4,5,7,8

Promote, protect, expand

Turlington’s distinctively shaped bottles were more than eye-catching – they reflected a shrewd business strategy.

At a time when English medicines were unregulated, Turlington promptly acquired one of the country’s first medical patents.1,3 Granted by King George in 1744 and lasting until 1758, the patent gave Turlington the legal right to prosecute imitators and widely promote his ‘miracle cure’ – a task he embraced with gusto.1,3,8

‘He had the cachet of having the king’s approval of his medicine, a fake coat of arms, a memorable name, a booklet given free with every purchase, a fixed price, and testimonials from satisfied customers who provided information on ailments that could be treated successfully with Balsam of Life,’ note Jones and Vegotsky.1

In 1748, Turlington extended his patent to include Britain’s North American colonies. Geographic expansion soon followed with sales to the emerging United States, Canada, the West Indies and, yes, Australia. Of course, he also pushed into Scotland, Ireland and Europe.1,3,8–10

Did Turlington’s balsam work?

With so many ingredients in varying amounts, used to treat a wide range of conditions, it’s difficult to say how effective the balsam truly was. At best, balsams exhibit anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and antimicrobial effects.11

Whether it worked or not, Turlington’s balsam left an enduring legacy – in pharmacy history, and also on collectors’ shelves.

References

- Jones O, Vegotsky A. Turlington’s Balsam of Life. Northeast Historical Archaeology. 2016;45:1.

- Dayton L. Friar’s Balsam has a place in modern life. Australian Pharmacist 2024;43(7):66.

- Abbott A. Turlington’s Balsam of Life: Colonial American snake oil? University of Central Florida, Center for Humanities and Digital Research.

- Pope A. Turlington’s Balsam, the 18th-century cure-all. Canadian Geographic 2016 7 July.

- Griffenhagen GB, Young JH. Old English patent medicines in America. Contributions from The Museum of History and Technology: Paper 10. Project Gutenberg EBook 30162.

- Dilworth LL, Riley CK, Stennett DK. Chapter 5 – Plant Constituents: Carbohydrates, oils, resins, balsams, and plant hormones. Pharmacognosy, Academic Press 61–80 2017.

- Jones OR. Essence of Peppermint, A history of the medicine and its bottle. Hist.Archaeol. 15(2):3, 28, 33.

- Kemp J. Bottles 1. Turlington’s Balsam of Life: the 1754 design. Cures All Diseases.com. 2020.

- Young JH. The Toadstool Millionaires: Chapter 1. Quackwatch. 2002 29 Apr.

- Keys R. Turlington’s Balsam of Life. The Adverts 250 Project. 2022 17 Feb.

Deborah Williams at the Chemist Warehouse Australian Open pop-up pharmacy[/caption]

Deborah Williams at the Chemist Warehouse Australian Open pop-up pharmacy[/caption]

Rebecca Davies[/caption]

Rebecca Davies[/caption]

Professor Clare Collins[/caption]

Professor Clare Collins[/caption]

Associate Professor Trevor Steward[/caption]

Associate Professor Trevor Steward[/caption]