As US regulators flag new warnings, the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) and Australian experts have weighed in on what the evidence shows.

Paracetamol has widely been considered the safest analgesic to relieve fever and pain during pregnancy. Fever higher than 38.9°C for at least 24 hours during pregnancy is linked to higher chances of miscarriage, preterm birth, stillbirth and certain malformations including neural tube defects like spina bifida.

Yet the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced it intends to add a warning label to the medicine, citing a ‘possible association’ between autism in children and the use of acetaminophen (paracetamol) during pregnancy.

This proposed regulation change, along with updated advice given to the American Academy of Pediatrics among other medical groups, follows an announcement from the US President linking acetaminophen (Tylenol) (known as paracetamol in Australia) to autism – calling on pregnant women to avoid it.

Australia’s Chief Medical Officer Micahel Kidd has rejected claims about the use of paracetamol in pregnancy and the risk of developing ADHD or autism. So what are other experts saying?

TGA: ‘safe for use in pregnancy’

Paracetamol remains Pregnancy Category A in Australia, meaning that it is considered safe for use in pregnancy, a spokesperson for the TGA told Australian Pharmacist.

‘The use of medications in pregnancy is subject to clinical, scientific and toxicological evaluation at the time of registration of a medicine in Australia,’ the spokesperson said.

‘Paracetamol has been taken by a large number of pregnant women and women of childbearing age without any proven increase in the frequency of malformations or other harmful effects on the fetus having been observed.’

Paracetamol is still the recommended treatment option for pain or fever in pregnant women when used as directed, the TGA said.

‘Importantly, untreated fever and pain can pose risks to the unborn baby, highlighting the importance of managing these symptoms with recommended treatment.

The spokesperson said that the TGA maintains robust post-market safety surveillance and pharmacovigilance processes for all medicines registered in Australia, including paracetamol.

‘When safety signals are identified for a medicine, they are subject to detailed clinical and scientific investigation to confirm that a safety issue exists, and if confirmed, what regulatory actions are most appropriate to mitigate the risk,’ the spokesperson said. ‘The TGA has no current active safety investigations for paracetamol and autism, or paracetamol and neurodevelopmental disorders more broadly.’

Australia is not the only nation holding firm; international peer regulators, such as the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, continue to advise that paracetamol be used according to the approved Product Information.

In its 2019 review, the European Medicines Agency also determined that the available evidence on paracetamol’s effects on childhood neurodevelopment is inconclusive.

Is there any evidence linking paracetamol in pregnancy with autism?

Some systematic reviews have reported associations between paracetamol use in pregnancy and autism in children – usually prolonged, high-dose use that exceeds recommendations.

Of central interest to the US Government’s claim is a 2025 systematic review which made the claim of ‘strong evidence of a relationship between prenatal acetaminophen use and increased risk of ASD in children’.

But the quality of these studies have been subject to significant critical review.

Professor Margie Danchin, a paediatrician and group leader of the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute’s Vaccine Uptake Group, refuted the evidence base, made up of observational studies, linking paracetamol to autism.

‘The cause of fever for the women in those studies is probably what caused the problems later on developmentally for the children, not the fact that they took Panadol for that fever.’

Additionally, Prof Danchin said many of the women who participated in these studies were asked several years postpartum whether they took paracetamol during pregnancy, further undermining accuracy.

More recent and robust studies contradict these claims and support the prevailing evidence that paracetamol is not causally linked to autism or ADHD, the TGA said.

Experts point to a Swedish cohort study as the most persuasive evidence on paracetamol and autism. Published last year, it analysed records for nearly 2.5 million children born between 1995 and 2019, identifying autism diagnoses and verifying whether mothers used paracetamol during pregnancy.

Crucially, the investigators conducted a sibling-comparison analysis, assessing pairs in which one child was prenatally exposed to paracetamol and the other was not. Because siblings share much of their genetics, household environment and maternal health influences, this approach helps isolate the impact of specific factors such as paracetamol.

In the largest study of its kind to date, no association was found between prenatal paracetamol exposure and autism.

Imparting safe and accurate information

Prof Danchin called the claim linking acetaminophen exposure in utero to autism ‘disinformation’.

‘At the moment, the biggest issue at play is trust,’ she said.

The danger of ‘repeatedly repeating myths’ is that it further entrenches them.

‘That sort of repetition becomes very sticky. People hear it all the time, and it becomes harder and harder to counter,’ Prof Danchin said.

However, health professionals should ensure the right messages get across, she said.

When counselling patients on paracetamol use in pregnancy, PSA has advised pharmacists to take the following approach:

- communicate to consumers that no studies have found a causal link between paracetamol use in pregnancy and autism

- communicate to consumers that paracetamol remains safe for use in pregnancy for appropriate management of pain and fever

- ensure pregnant women continue to be supported to meet their clinical needs

- if and when required, refer consumers with heightened concerns to their GP or maternal health team.

‘We need to see a lot more medical and scientific voices standing up and being very clear and simple, and having their message as appealing and as easy to understand,’ Prof Danchin said. ‘People need to trust the people they’ve always trusted to communicate the correct health information and the science to them.’

Ruth Nona[/caption]

Ruth Nona[/caption]

Kate Gunthorpe MPS[/caption]

Kate Gunthorpe MPS[/caption]

Madison Low[/caption]

Madison Low[/caption]

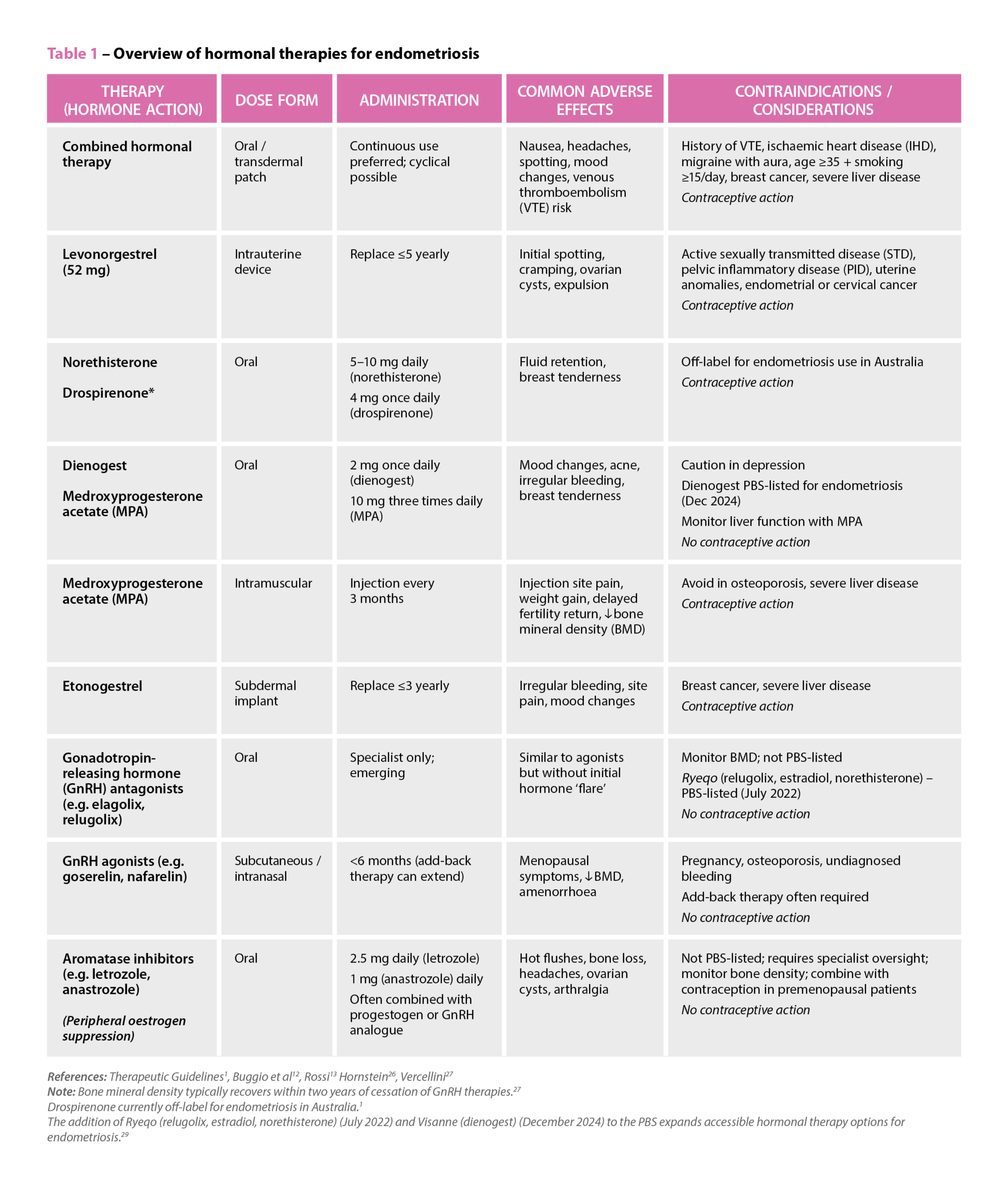

References: Therapeutic Guidelines

References: Therapeutic Guidelines

Genevieve Adamo MPS (Image: Steve Christo Photography)[/caption]

Genevieve Adamo MPS (Image: Steve Christo Photography)[/caption]