Complex, undiagnosed pelvic pain can often leave patients in awful limbo. Pharmacists can help them understand what drives – and can interrupt – pain.

For some people, severe and chronic pelvic pain persists despite extensive investigations and no confirmed diagnosis of endometriosis. In some cases, pain continues even after surgery to remove endometriosis lesions.

Other people may experience overlapping pain conditions such as bladder pain syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome or musculoskeletal dysfunction.

Without a diagnosis, these people often fall through the cracks – left managing debilitating pain with little clarity, validation or structured care.

‘Early intervention in pelvic pain is crucial to reduce the risk of maladaptation, central sensitisation and the significant social, work-related and mental health impacts of untreated pain,’ according to the Chairperson of Chronic Pain Australia, Nicolette Ellis MPS, a pharmacist.

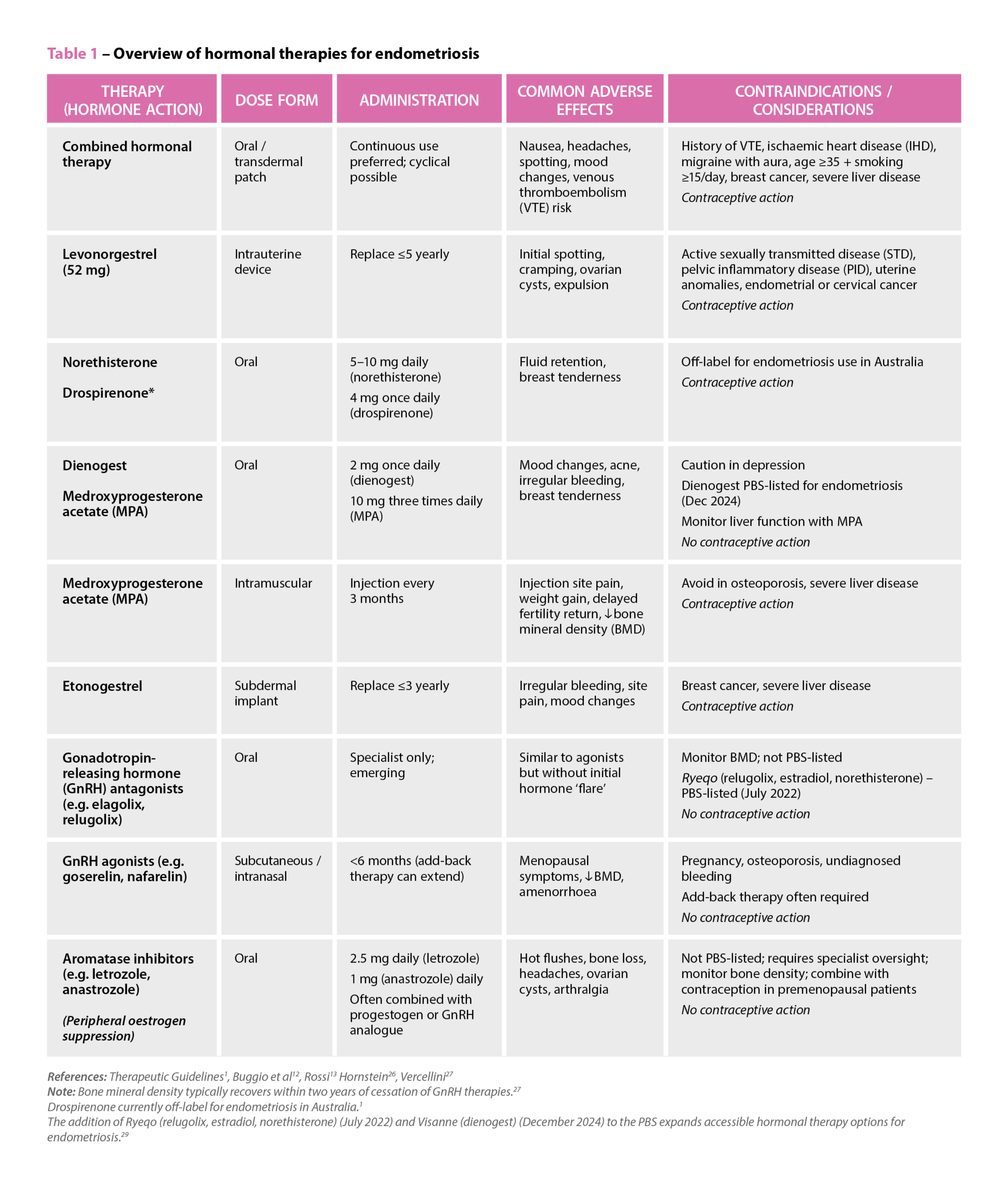

Even without a confirmed diagnosis, commencing appropriate hormonal therapy and analgesics is recommended, she says. Medicines alone are rarely sufficient, and a pelvic pain physiotherapist is often the most important allied health referral to address muscle overactivity and contributors to persistent pain.

Ms Ellis says chronic pelvic pain is best managed through a team-based approach, where pharmacists, GPs, physiotherapists, psychologists and specialists each address different contributors to the pain experience. Clear communication and shared understanding between disciplines can improve outcomes significantly.

‘Around two in three people with chronic pain experience a secondary mental health condition,’ Ms Ellis says.

‘Catastrophising, rumination and helplessness are very common, especially when patients have been repeatedly bounced around the health system without answers.’

Free pain-specific supports like MindSpot, as well as peer networks such as PainLink helpline 1300 340 357 and Chronic Pain Australia’s support groups, can be invaluable, she says, alongside psychologists with an interest in pain.

Chronic vs acute pelvic pain

Acute pelvic pain typically presents suddenly, says Ms Ellis.

Often, it comes with red flags such as severe unilateral pain, fever, vomiting or rapid escalation, warranting urgent medical review. Chronic pelvic pain, in contrast, develops over months or years. It often follows patterns linked to menstrual cycles, bladder or bowel function, stress or muscle tension.

Many people with pelvic pain also dismiss their symptoms. Ms Ellis says they normalise heavy bleeding, bloating or discomfort, which can delay recognition that these patterns are not normal and require assessment. Chronic pelvic pain is defined as pain persisting for more than 3 months that does not need to occur daily. Pain that occurs on more than 10–15 days per month over a 3-month period is generally considered to meet the criteria.

‘A lack of diagnosis should never limit a clinician’s ability to treat, educate or support a patient in managing their pain.’ Ms Ellis stresses. See overleaf for two interesting case studies on undiagnosed pelvic pain that were not endometriosis.

Box 1 – Referral pathways

| Pharmacists seeking help for patients with chronic or unexplained pelvic pain can refer to:

These clinicians can:

|

Case 1

Tahnee Simpson – Pharmacist specialising in menopause, pelvic and vaginal pain, Keparra Compounding Pharmacy, Brisbane, Queensland

Ms VS, aged 28, was referred by her pelvic health physiotherapist after struggling with persistent vulvar pain and fear of penetration.

She had a long-standing history of vaginismus, with ongoing difficulty using tampons or tolerating vaginal examinations. Her primary goal was to build confidence using dilators and, eventually, enjoy pain-free intercourse.

A burning sensation localised to the vaginal opening (introitus), especially during attempted insertion, was described by Ms VS.

There were no spontaneous flares or constant pain; symptoms were clearly provoked. A concurrent sensation of rectal pressure suggested pelvic floor hypertonicity.

Ms VS had previously trialled oral amitriptyline at a low dose (10 mg) but discontinued it due to adverse effects and lack of symptom relief.

Simple analgesics such as paracetamol and ibuprofen had also been used without benefit.

She was under the care of a gynaecologist who had previously diagnosed vaginismus and more recently confirmed provoked vestibulodynia1 after ruling out infection, dermatological and hormonal causes.

Provoked vestibulodynia, sometimes grouped under the broader term vulvodynia, is a chronic vulvar pain condition lasting more than 3 months without an identifiable cause.

It affects an estimated 3–7% of women and remains underdiagnosed, despite its significant impact on sexual function and quality of life.

For Ms VS, a prior attempt at pelvic physiotherapy had been cost-prohibitive, but a recent reassessment by a new physiotherapist identified significant pelvic floor tension contributing to her pain.

The prescriber contacted our pharmacy to collaborate on a desensitisation approach that would support dilator therapies.

We initiated a combination of topical and suppository-based therapy.

A compound of topical amitriptyline/gabapentin/lidocaine in a penetrating transdermal base was applied (0.5 mL) to the vestibule up to three times daily before dilator use.

The specific base selection for this patient was chosen for its low-irritant profile and effective mucosal absorption.

To address deep muscular spasm, diazepam combined with baclofen suppositories were supplied for rectal or vaginal use before or after therapy sessions. Counselling focused on expectation-setting that improvements would likely be gradual and interlinked with physiotherapy outcomes.

We discussed Mi-Gel® the proprietary compounded formulation (amitriptyline + estriol) as a future maintenance option.

Within weeks, Ms VS reported increased tolerance to early-stage dilators and reduced pelvic floor tension and felt more control over her pain condition with the provided toolkit of options available to her.

Her experience highlighted the value of collaborative, compounded care in addressing under-recognised conditions like vestibulodynia.

References

- Faye RB, Mikes BA. StatPearls. Treasure Island(FL): StatPearls Publishing. 2025.

Case 2

Nicolette Ellis MPS – Pharmacist and chronic pain advocate, Chairperson, Chronic Pain Australia. Brisbane, Queensland

Ms AR, a 33-year-old mother of two, presented with a longstanding history of severe pelvic pain, heavy dysmenorrhoea and recurrent bacterial vaginosis (BV).

She was using ibuprofen 400 mg TDS PRN and paracetamol 1 g QID PRN after previously trialling metronidazole and clindamycin vaginal treatments – both of which were either poorly tolerated or she was allergic to. Vulval hypersensitivity consistent with suspected vulvodynia was reported and also unpredictable non-cyclical pain episodes that interfered with daily activities.

Her symptoms had intensified postpartum, with menstrual changes, weight gain despite appropriate lifestyle measures, and elevated insulin markers indicating postpartum insulin resistance.

A history of gestational diabetes raised the possibility that pre-diabetes and associated metabolic inflammation were contributing to her worsening pelvic pain.

The importance of ongoing monitoring, including HbA1c, fasting glucose and insulin, lipid profile and thyroid function, was discussed as part of her long-term care plan. Although metformin was among potential options, she preferred to continue with lifestyle management and structured monitoring.

A significant consultation component involved helping her understand persistent pelvic pain neuroplasticity. We explored how hormonal variation, pelvic floor tension and repeated nociceptive input can sensitise pain pathways over time.

This explanation provided validation and helped reduce her fear that a missed diagnosis was the cause of her pain.

Given her intolerance to antibiotics, we implemented both acute and maintenance treatment using boric acid 600 mg vaginal pessaries, which provided meaningful reduction in BV recurrences.*1 This was supported with vaginal probiotics, ideally those containing Lactobacillus crispatus.

To help break the cycle of dysmenorrhoea-triggered pain amplification, menstrual suppression was considered.

An IUD was avoided due to vulval and cervical sensitivity. However, plans were made to trial continuous hormonal contraception instead.

A multidisciplinary approach was essential. Ms AR was referred to a pelvic pain physiotherapist to address pelvic floor overactivity and muscular guarding.

Her partner was also included in the management plan, learning pelvic floor release techniques that provided practical support at home during pain spikes.

For acute pelvic muscle spasm, diazepam 5 mg vaginal pessaries were compounded to offer targeted relief without significant systemic effects.

Although her symptoms did not fully resolve, Ms AR achieved improved pelvic muscle function, fewer BV flares, clearer metabolic monitoring and a more cohesive understanding of her condition.

This case reinforces the importance of offering patients meaningful hope, even when no clear diagnosis, such as endometriosis or adenomyosis, is found.

*This case occurred before contemporary evidence supporting partner treatment for recurrent BV became available.

References

- Vodstrcil LA, Plummer EL, Fairley CK, et al. Male-partner treatment to prevent recurrence of bacterial vaginosis. N Eng J Med 2025;392:947–57.

Ruth Nona[/caption]

Ruth Nona[/caption]

Kate Gunthorpe MPS[/caption]

Kate Gunthorpe MPS[/caption]

Madison Low[/caption]

Madison Low[/caption]

References: Therapeutic Guidelines

References: Therapeutic Guidelines