Anxiety is the most common mental health condition in Australia, and research shows the pandemic has only exacerbated the issue. Are we doing enough to support those who experience it?

When ABC News Breakfast weather presenter Nate Byrne had his first-ever panic attack on live TV in 2018, he thought his career was over.

Standing under the studio lights, Mr Byrne felt his heart racing as he gasped for breath and tried to ignore the voice in his head urging him to run. Drenched in sweat, he made it to the end of his segment before doubling over to catch his breath, light-headed and confused about what was happening.

Fifteen minutes later, ready to front the camera again, he had his second panic attack. ‘This time, it was much worse – I started shaking, my vision narrowed, my heart was pounding like I’d run a marathon, I couldn’t breathe.

‘I needed to be anywhere else, and I had no idea why,’ Mr Byrne remembers. ‘I’d later find out that what I was experiencing was diagnosable and manageable, but in that moment, I thought my career was over … My place of joy and purpose was now an existential hellhole, corrupted in a quarter of an hour.’

Mr Byrne says the experience – and his continuing journey with anxiety, of which panic attacks are a subset – has changed his perspective on mental health.

‘This time, it was much worse – I started shaking, my vision narrowed, my heart was pounding like I’d run a marathon.’

Nate Byrne

‘While I appreciated that things like anxiety and depression are very much real, I had no idea about the complete lack of control you can sometimes have over your brain, nor the ways in which it can take over,’ he says. ‘Watching back the videos of me having a panic attack on live television has shown me that it’s not always obvious what’s going on from the outside.’

Rising anxiety

Up to 40% of Australians will experience a panic attack like Mr Byrne’s at some point in their life.1 And while not every panic attack progresses to panic disorder or other mental illness, early intervention is important.

References to pathological anxiety2 were recorded and identified as medical disorders by the ancient Greeks. For people with anxiety disorders, ‘anxious thoughts, feelings or physical symptoms can become chronic, severe and upsetting, and interrupt daily life’, according to the Australian Psychological Society.3 This includes generalised anxiety disorder (GAD), social anxiety, specific phobias and panic disorder.4 Of these, social anxiety is the most common in Australia, followed by specific phobias, GAD and panic disorder.4

Mr Byrne experienced some of the classic symptoms of a panic attack: sweating, increased heart rate, shortness of breath and light-headedness.4,5

More than 3.2 million Australians had an anxiety-related condition in the latest Australian Bureau of Statistics report on mental health (2018).6 And all mental illness, which includes anxiety, costs the economy up to $220 billion per year, according to the Productivity Commission.7

This was exacerbated during the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic, with cases of anxiety disorders and major depressive disorder increasing by more than 25% worldwide, according to University of Queensland researchers in the first study to quantify the prevalence and burden of anxiety and depressive disorders as a result of the pandemic in 2020 by age, sex and location globally.8

Mental Health Australia Chief Executive Officer Leanne Beagley says the increase might also be explained by a greater awareness of anxiety within the community. ‘Through COVID, people have been encouraged to recognise that they’re under more stress and might be more disconnected and lonely,’ she says.

‘It’s less stigmatising to put your hand up and say you’re struggling.’

She says the research also suggests rising anxiety is linked to uncertainty.

‘This is why younger people seem more affected than older people,’ she says. ‘For example, the rates among over 55s are not increasing the way they are in young people, particularly in young women. And it’s probably because it’s about the future.’

A recent meta-analysis of 36 studies indicated that prevalence rates of anxiety9 (along with depressive and eating pathology symptoms) between the pre- and peri-COVID-19 eras showed that, globally, respondents experienced significantly elevated rates of psychopathology symptoms during the onset of the pandemic.

Hospital pharmacists supporting patients

Hun Liang Oon is Deputy Chief Pharmacist (Operations) of Mental Health Pharmacy Services within Western Australia’s North Metropolitan Health Service.

He says cases of anxiety disorders managed in hospitals are ‘usually on the severe end of the spectrum’.

‘This is usually failing most interventions in the community. We hardly see any cases of GAD

[or] panic disorders in hospital as the sole reason for admission,’ he says. ‘Of the anxiety spectrum disorders, the ones we usually see present to hospitals are post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), or as part of another comorbid mental health disorder.’

Mr Oon says psychosocial interventions remain first-line treatment for most anxiety disorders. ‘The pharmacotherapy we use includes high-dose antidepressants, adjunct antipsychotics, pregabalin, etc, and sometimes long-term benzodiazepines as a last resort. There are other treatments for specific anxiety spectrum disorders (for example, highdose clomipramine for OCD).’

Given the anxiety disorders that patients in public hospitals present with are hard to treat, Mr Oon says there is a need for ‘more specialised pharmacists working in the mental health setting’.

‘Unfortunately,’ at the present time, he believes, ‘there is a lack of a clear pathway for mental health specialisation for clinical pharmacists.’

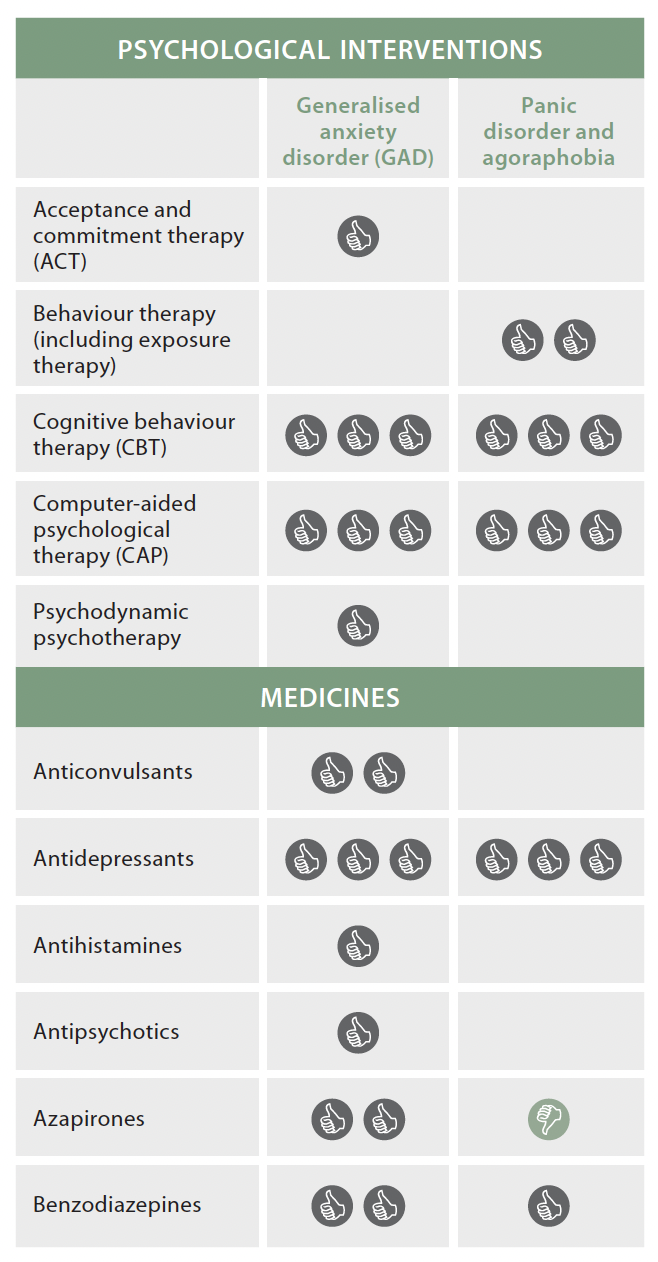

Table 1 – Interventions for anxiety

Source: Adapted from Beyond Blue10 A thumbs up means the treatment has worked in research studies, but does not mean it will work equally well for every person. A thumbs down signifies that studies have shown that this treatment did not work for that disorder and the pros and cons should be discussed with a GP or mental health professional.

A consumer perspective

When Helen Mees started to experience tiredness and nausea – symptoms of her kidney disease – 40 years ago, she was treated like ‘a neurotic young woman who needed to get a life’.

It took her 3 years to find a doctor willing to help, and another 2 years before she had a formal diagnosis of chronic kidney disease (CKD).

The stress of knowing she was ill and that her symptoms were not being taken seriously had a profound impact on her mental health.

‘There’s nothing worse than being unwell and tired most of the time, and having no one believe you, to generate anxiety,’ she says.

‘I got incredibly anxious and distressed very easily, and it took a lot of work to move away from that response to things.’

Today, Ms Mees is a passionate consumer advocate, working with Health Consumers Queensland to ensure patients’ voices are heard.

She also volunteers with Lifeline and sits on multiple committees for safety and quality in healthcare.

Through this work – and her personal experience – she has seen how the health system treats those living with anxiety.

‘It’s almost like a lack of moral fibre to admit you’ve got anxiety,’ she says.

‘Unless you’ve experienced it longterm, or you’ve really worked hard to understand it, people who’ve never experienced anxiety just don’t get it.’

MHFA and destigmatising healthcare

Mental Health First Aid (MHFA) is a good starting point for pharmacists to support patients with anxiety, says PSA’s Manager of Training and Delivery, Kevin Ou.

‘MHFA has been shown to have a positive impact11 on pharmacy students by reducing mental health stigma, improving recognition of mental disorders, and improving confidence in providing services to patients with mental illness in the pharmacy setting,’ he says.

‘There is also research12 to show that patients feel more comfortable discussing mental illness when pharmacists are MHFA trained.’

Recognising and understanding the signs and symptoms of anxiety is important, as is understanding why people take certain medicines.

‘It may not be immediately obvious that someone is taking a medicine because of anxiety (for example, gastrointestinal medicines, sleeping tablets and certain herbs and vitamins),’ Mr Ou says.

‘If we can have a non-judgmental approach to discussing these medicines, we can create safe spaces to allow people to talk about their health needs, which results in quality use of medicines and medicine safety, and ultimately better patient outcomes.’

Figure 1 – Anxiety in Australia

4 types of anxiety:

3.2 million Australians had an anxiety-related condition in 2017–18 $220 billion cost to the economy each year due to mental illness Anxiety-related conditions affect 24.6% of women aged 15–24 years and 13.9% of men aged 15–24 years 25% increase in anxiety disorders and major depressive disorder worldwide during the pandemic |

References: Beyond Blue4, ABS6

Long-term benzodiazepine use – for some

This non-judgmental approach should extend to benzodiazepines, which are often prescribed for immediate effect rather than longer-active, less-addictive medicines such as beta blockers, antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

However, there is a growing understanding that benzodiazepines can be used appropriately, long-term, in the right patients for the right conditions.

A systematic review13 published in The Lancet in 2019 ‘showed that benzodiazepine monotherapy for generalised anxiety disorder was effective’, while an article published in the British Journal of Psychiatry in 2021 found ‘the risk of abuse or dependence is also overestimated and is relatively uncommon in patients who do not have a previous history of substance abuse’.14

Australia’s Therapeutic Guidelines also states: ‘Maintenance therapy may be appropriate in patients who have not responded to other treatments and in those who are stable on a long-term regimen with good clinical response.’15

While evidence shows that getting off medicines is not the aim of every patient, the perceptions of health professionals – often emboldened through real-time prescription monitoring – can stigmatise rather than support patients who use benzodiazepines as part of an evidence-based long-term treatment plan.

‘Pharmacists should understand what effective treatments are available for anxiety disorders, which include both pharmacological and non–pharmacological therapies,’ Mr Ou says.

‘A good place to start is Beyond Blue’s A Guide to What Works for Anxiety,11 which can be a useful resource to engage with patients and provides evidence ratings.’

What helped these patients?

After his first panic attacks, Nate Byrne went straight to his GP. He was prescribed propranolol. It ‘worked so successfully, I was able to be on air that evening’.

He initially took one tablet per day before going on air, before dropping to half a tablet after about a month. Five weeks after the first panic attack he had scaled back to as-required usage.

‘There’s nothing worse than being unwell and tired most of the time, and having no one believe you, to generate anxiety.’

Helen Mees

‘Luckily, I haven’t experienced any adverse effects, and find they work well within about 10–15 minutes,’ he says.

‘For me, having beta blockers available is great – it gives me confidence that a panic attack won’t ruin my day or prevent me from being able to do my work, which people often rely on for safety information. It’s a wonderful comfort that I very rarely have to rely on.’

Having a support system in place at work is also vital.

‘It’s crucial for me,’ Mr Byrne stresses, ‘that my team are aware of what happens for me, so that they can quickly recognise it and help to cover for me while I gather myself. It doesn’t come up very often, but when it does, it’s incredibly comforting to know that they are there to make sure that the train stays on the tracks.’

And while Ms Mees’s anxiety subsided once she finally got her CKD diagnosis, many people aren’t as fortunate. She says it’s important for pharmacists and other healthcare professionals to validate patients’ feelings. ‘For some people, there’s no [external] explanation for why they’re anxious, and so they feel ashamed. And shame is a really soul-destroying feeling – it gets in the way,’ Ms Mees says.

‘I think the most powerful thing any health professional can do is reduce the shame and make it clear that anxiety happens to all sorts of people, for all sorts of reasons, and that it can be managed.

‘That’s the thing I’ve learned with Lifeline – when people are struggling, what they need most of all is hope that things will get better.

FOR MORE INFORMATION on PSA’s Self Care anxiety card see psa.org.au/programs/self-care/

References

- Beyond Blue. Panic disorder. 2022. At: beyondblue.org.au/the-facts/anxiety/types-of-anxiety/panic-disorder

- Crocq MA. A history of anxiety: from Hippocrates to DSM. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2015;17(3):245–6.

- Australian Psychological Society. Anxiety disorders. At: https://psychology.org.au/for-the-public/psychology-topics/anxiety

- Beyond Blue. Types of anxiety. At: www.beyondblue.org.au/the-facts/anxiety/types-of-anxiety

- Panic attack. At: www.healthdirect.gov.au/panic-attack

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Mental health. At: www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/mental-health/mental-health/latest-release

- Australian Government. Productivity Commission. A brief overview of the mental health inquiry report. At: pc.gov.au/news-media/speeches/mental-health

- Santomauro DF, Mantilla Herrera AM, Shadid J et al. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2021;398(10312:1700–12. At: thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(21)02143-7/fulltext

- Schafer KM, Lieberman A, Sever AC, et al. Prevalence rates of anxiety, depressive, and eating pathology symptoms between the pre- and peri-COVID-19 era: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2022. Epub 2022 Feb 1.

- Reavley N, Morgan A, Jorm A, et al. A guide to what works for anxiety: an evidence-based review. 3rd Beyond Blue: Melbourne, 2019.

- O’Reilly C, Bell, SJ, Kelly PJ, et al. Impact of mental health first aid training on pharmacy students’ knowledge, attitudes and self-reported behaviour: a controlled trial. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 2011;45(7)549–57.

- Dollar KJ, Ruisinger JF, Graham EE. Public awareness of mental health first aid and perception of community pharmacists as mental health first aid providers. Jam Pharm Assoc (2003) 2020;60(5S):S93–7.e1.

- Slee A, Nazareth I, Bondaronek P, et al. Pharmacological treatments for generalised anxiety disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet 2019;393(10173):768–77.

- Silberman E, Balon R, Starcevic V, et al. Benzodiazepines: it’s time to return to the evidence. Br J Psychiatriatry 2020;218(3) 125–7.

- Therapeutic Guidelines. Overview of anxiety and associated disorders. At: www.tg.org.au/

Dr Malcolm Gillies[/caption]

Dr Malcolm Gillies[/caption]

PSA SA/NT Pharmacist of the Year Natasha Downing MPS[/caption]

PSA SA/NT Pharmacist of the Year Natasha Downing MPS[/caption]

PSA SA/NT ECP of the Year Raymond Truong MPS[/caption]

PSA SA/NT ECP of the Year Raymond Truong MPS[/caption]

PSA SA/NT Intern of the YearChloe Hall MPS[/caption]

PSA SA/NT Intern of the YearChloe Hall MPS[/caption]

PSA SA/NT Lifetime Achievment Award recipient Peter Halstead FPS[/caption]

PSA SA/NT Lifetime Achievment Award recipient Peter Halstead FPS[/caption]

Pharmaceutical Society Gold Medal recipient Amelia Thompson[/caption]

Pharmaceutical Society Gold Medal recipient Amelia Thompson[/caption]