Ordinarily used to treat other conditions, this trycylic antidepressant performed well in a recent trial on people with IBS.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is estimated to affect 10% of people around the world.1,3

It is a chronic, functional bowel disorder, and people can experience a range of symptoms (e.g. abdominal pain or discomfort associated with changed bowel habits in stool form or frequency, manifesting as constipation and/or diarrhoea).1,3 Diagnosis is based on symptoms, and management focuses on factors that likely trigger or precipitate the symptoms, with certain treatments only working for specific types of IBS.1,3

Unfortunately, the aetiology and pathogenesis of IBS is complex, and there is no cure.1,2 Therefore, depending on the type of IBS, initial therapy may include dietary changes (to avoid triggers), psychological therapies, adequate intake of appropriate types of fibre to support good bowel function, and modification of the gut microbiota.1 Common pharmacological therapies such as some laxatives, anti-diarrhoeals (e.g. loperamide), antispasmodics (e.g. peppermint oil, hyoscine butylbromide, mebeverine) may be used depending on the symptoms being managed.1

Examples of other medicines used – e.g. in IBS with diarrhoea (IBS-D) – include rifaximin (a rifamycin that inhibits bacterial RNA polymerase),4 which may improve stool consistency and general symptoms by changing the gut microbiota. Small trials have also reportedly found 5-HT3 receptor antagonists (e.g. ondansetron) to improve stool consistency in IBS-D.1

In people experiencing severe pain and who do not respond to first-line treatments, antidepressants such as tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may sometimes be tried for their brain-gut modulatory effects, which is independent of their effects on anxiety or depression.1 Some evidence suggests these medicines may reduce visceral hypersensitivity, which is commonly involved in IBS (approximately 40% of people).5 However, its benefits are reportedly uncertain, with most studies being small, underpowered and not conducted in primary care settings.2

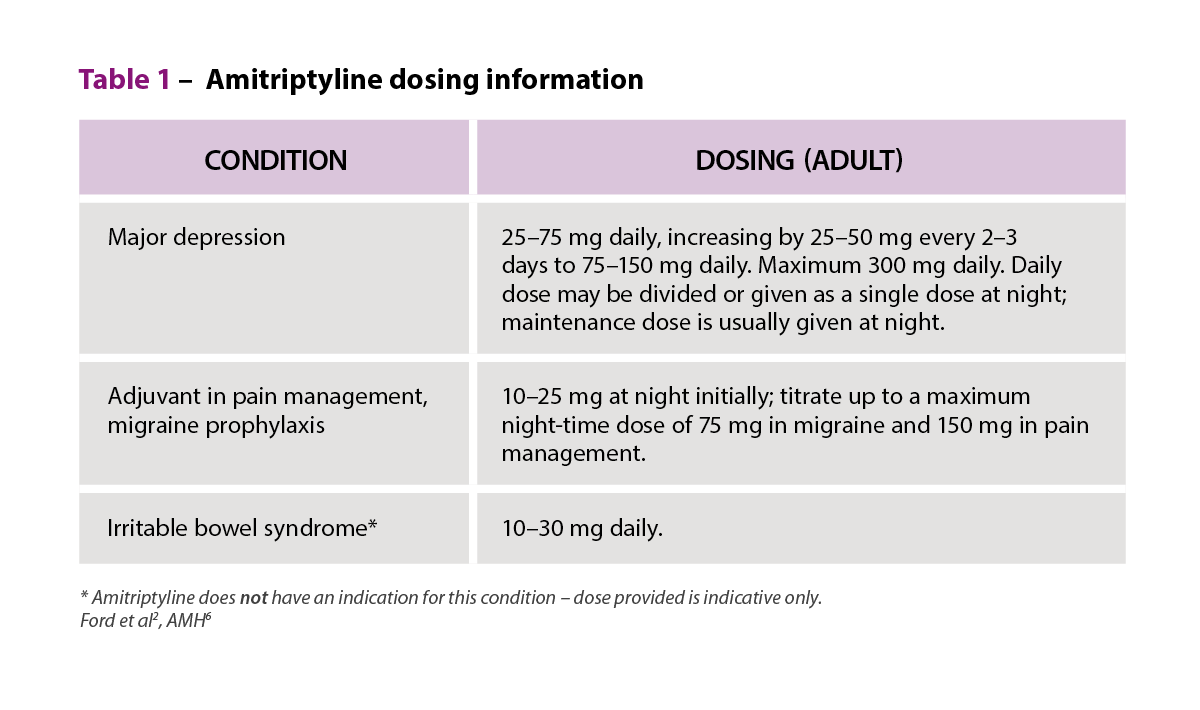

Amitriptyline is a TCA, which inhibits noradrenaline and serotonin reuptake into pre-synaptic terminals.6 Amitriptyline is used in the management of major depression, along with other indications (e.g. adjuvant in pain management, for migraine prophylaxis, and nocturnal enuresis [bedwetting] under specialist advice).6

A recently published randomised, placebo-controlled trial of 463 participants investigated the effectiveness of low-dose amitriptyline for 6 months (titrated from 10 mg to a maximum of 30 mg once daily over 3 weeks) as second-line therapy for IBS in primary care. The participants could have IBS of any subtype, with ongoing symptoms despite dietary changes and first-line therapies, normal full blood count and C-reactive protein, negative coeliac serology, and no evidence of suicidal ideation.2

Compared to placebo (n = 231), the participants receiving low-dose amitriptyline (n = 232) had significantly improved global IBS symptoms as measured by their IBS Severity Scoring System (IBS-SSS) score at 6 months (-27·0, 95% confidence interval (CI) -46·9 to -7·10; p = 0·0079)2. There was also increased odds of symptom relief, a key secondary outcome, as measured by subjective global assessments of IBS symptoms (odds ratio 1·78; 95% CI 1·19 to 2·66; p = 0·0050)2. Adverse effects of amitriptyline were consistent with its known adverse effect profile related to its anticholinergic effects.2

Compared to placebo (n = 231), the participants receiving low-dose amitriptyline (n = 232) had significantly improved global IBS symptoms as measured by their IBS Severity Scoring System (IBS-SSS) score at 6 months (-27·0, 95% confidence interval (CI) -46·9 to -7·10; p = 0·0079)2. There was also increased odds of symptom relief, a key secondary outcome, as measured by subjective global assessments of IBS symptoms (odds ratio 1·78; 95% CI 1·19 to 2·66; p = 0·0050)2. Adverse effects of amitriptyline were consistent with its known adverse effect profile related to its anticholinergic effects.2

The authors report that the effects of amitriptyline were greater in people with IBS with constipation (IBS-C) or IBS-D, lower baseline hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS)-anxiety scores, higher baseline IBS-SSS scores, and among men.2

However, they also point out some limitations: for instance, that over 80% of the participants had IBS-D or IBS with mixed bowel habits (IBS-M), meaning it was difficult to draw conclusions about the usefulness of low-dose amitriptyline in IBS-C or IBS which is unclassified (IBS-U)2. Similarly, the study recruited those with higher symptom severity, and unfortunately the study protocol had to be modified due to the COVID-19 pandemic, impacting on the ability for a longer treatment and follow-up at 12 months.2

Nevertheless, the authors conclude that amitriptyline (with appropriate support for enabling patient-led dose titration) is safe and well-tolerated, and should be offered as a second-line option compared to when first-line therapies have failed.2

While the authors have also reportedly planned a cost-effective analysis subject to funding,2 this current study would certainly add to the body of evidence to help clinical decision-making around considering amitriptyline in the management of IBS symptoms.

References

- Gastrointestinal Expert Group. Therapeutic guidelines: Irritable bowel syndrome in adults. Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Limited; 2022.

- Ford A, Wright-Hughes A, Alderson S, et al. Amitriptyline at low-dose and titrated for irritable bowel syndrome as second-line treatment in primary care (ATLANTIS): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2023;402(10414):1773–85.

- Cleveland Clinic. Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Symptoms, Causes & Treatment: Cleveland Clinic; 2023. At: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/4342-irritable-bowel-syndrome-ibs

- Australian Medicines Handbook. Australian Medicines Handbook – Rifaximin: Australian Medicines Handbook Pty Ltd; 2023.

- Cleveland Clinic. Visceral hypersensitivity: symptoms, treatment, causes & what it is: Cleveland Clinic; 2022 At: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/22997-visceral-hypersensitivity.

- Australian Medicines Handbook. Australian medicines handbook – Amitriptyline: Australian Medicines Handbook Pty Ltd; 2023.

‘We’re increasingly seeing incidents where alert fatigue has been identified as a contributing factor. It’s not that there wasn’t an alert in place, but that it was lost among the other alerts the clinician saw,’ Prof Baysari says.

‘We’re increasingly seeing incidents where alert fatigue has been identified as a contributing factor. It’s not that there wasn’t an alert in place, but that it was lost among the other alerts the clinician saw,’ Prof Baysari says.

Beyond the arrhythmia, AF often signals broader pathological processes that impair cardiac function and reduce quality of life and life expectancy.5 Many of these conditions are closely linked to social determinants of health, disproportionately affecting populations with socioeconomic disadvantage. Effective AF management requires addressing both the arrhythmia and its underlying contributors.4

Beyond the arrhythmia, AF often signals broader pathological processes that impair cardiac function and reduce quality of life and life expectancy.5 Many of these conditions are closely linked to social determinants of health, disproportionately affecting populations with socioeconomic disadvantage. Effective AF management requires addressing both the arrhythmia and its underlying contributors.4  C – Comorbidity and risk factor management

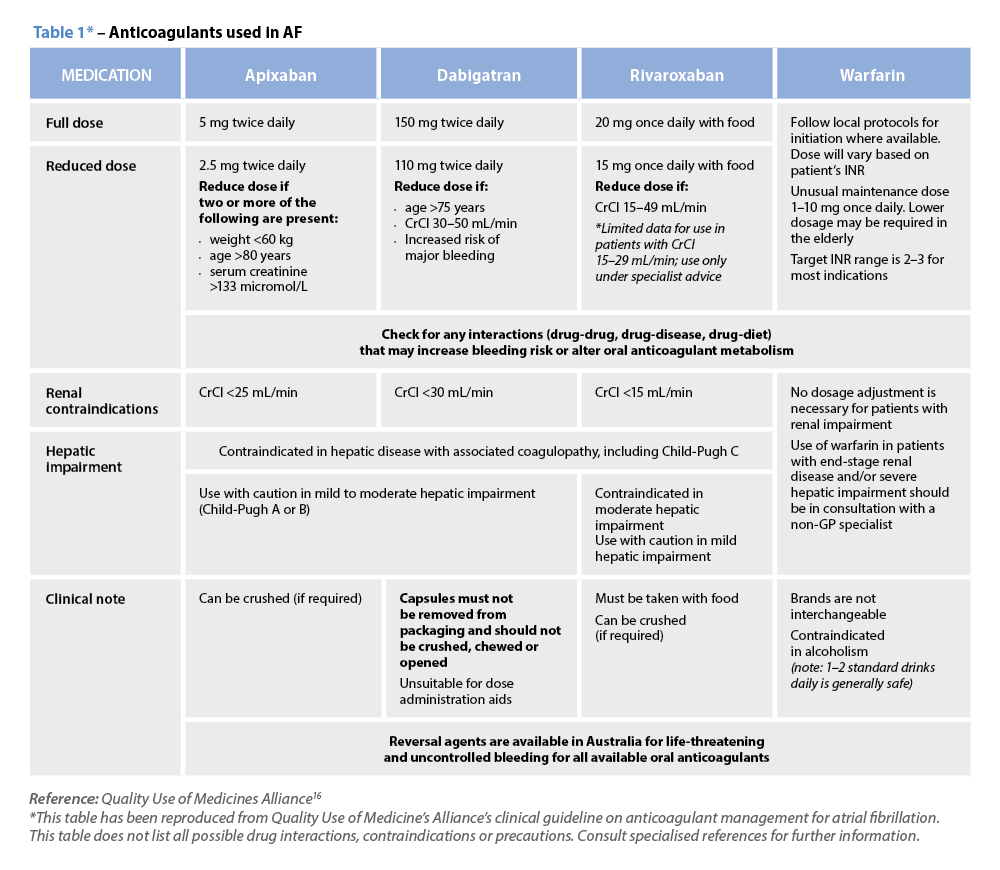

C – Comorbidity and risk factor management Warfarin

Warfarin