Antimicrobial use has declined in Australia during the pandemic, but the figures show there is no room for complacency.

The Fourth Australian report on antimicrobial use and resistance in human health, released last week by the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, found Australia continues to prescribe antimicrobials at much higher rates than most European countries.

In 2019, more than 40% of Australians had at least one antimicrobial dispensed in the community, and more than 26.6 million prescriptions were dispensed for antimicrobials.

Antimicrobial use in the community, based on defined daily doses per 1,000 people per day, was 22.9. In the Netherlands it is as low as 9.5, while the rate in Canada, which has a similar healthcare system to Australia, is 17.5.

The most used antibiotics were cefalexin, amoxicillin and amoxicillin–clavulanic acid. This is of concern, according to the report, as cefalexin and amoxicillin–clavulanic acid are first-line agents for very few conditions.

Although antimicrobial dispensing rates have been gradually declining since 2015, the commission’s Senior Medical Advisor Professor John Turnidge AO said this is a trend that must be maintained in order to slow the spread of resistance.

‘We’ve still got a long way to go to get to appropriate prescribing across the country,’ he told Australian Pharmacist.

‘We’re still a lot higher than our benchmark country, which is the Netherlands. We’ve still got high usage, it’s just better than previous years.’

Inappropriate antimicrobial prescribing

Despite the existence of therapeutic guidelines that detail when to prescribe antimicrobials, the appropriate dose and the length of time for use, inappropriate prescribing continues to be an issue, Prof Turnidge said.

This is particularly true for respiratory infections, which are largely viral. For example, according to the report for a number of general practices, more than 80% of people with acute bronchitis or sinusitis were prescribed antimicrobials when they are not recommended by the prescribing guidelines.

‘The most important message for patients and prescribers is that antibiotics are not needed for something like a head cold.’

‘When we prescribe antibiotics when they are not needed, we impose unnecessary costs on the patient, and expose them to the risk of side effects,’ Prof Turnidge said.

‘The most important message for patients and prescribers is that antibiotics are not needed for something like a head cold. Many GPs are coming on board, but there’s a huge amount of patient pressure – many patients go to the doctor expecting an antibiotic.’

A positive COVID effect

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a dramatic impact on the dispensing rates of antimicrobials, according to the report, with reductions of between 22% and 49% in dispensing of amoxicillin, cefalexin and doxycycline in 2020.

This could be due to a decrease in dispensing for seasonal respiratory infections such as colds and influenza, which saw a drop due to increased hand hygiene, staying at home when unwell, travel restrictions and social distancing.

‘We had very high use [of antimicrobials] in the community, but during COVID there was a significant drop in the use of certain antimicrobials,’ Prof Turnidge said.

‘As there have continued to be outbreaks of COVID, lockdowns and ongoing promotion of hand washing and social distancing in some states and territories, I imagine that the decrease may continue throughout 2021.’

Although the reduction in antimicrobial dispensing is positive, Prof Turnidge said it is important to keep the momentum going.

‘It’s one positive note we can take from COVID, and it’s a message I think we can really develop and get out to prescribers and patients that those things that cause coughs, colds and sore throats, they’re just like COVID. They don’t need antibiotics and they don’t get better with them anyway,’ he said.

‘I hope we’ll be able to keep the gains we’ve got and make even further improvements.’

Cautionary label for antibiotics remains important

To help address antimicrobial resistance, a new cautionary advisory label (CAL D) for antibiotics was released with the latest edition of the Australian Pharmaceutical Formulary and Handbook this year.

‘We had very high use [of antimicrobials] in the community, but during COVID there was a significant drop.’

Replacing decades of advice to take the medicines ‘until all used’ or ‘until all taken’, the label is an additional instruction with the words, ‘Take for the number of days advised by your prescriber’. If a patient is not aware of the prescribed duration of treatment and it is not specified on the prescription, the pharmacist should contact the prescriber to confirm the duration.

Completion of a recommended course of therapy with an antibiotic can improve therapeutic outcomes and reduce the incidence of relapse. However, taking antibiotics for longer than necessary does not improve outcomes and increases the risk of acquiring resistant bacterial strains.

Practical tips for pharmacists

In a companion document to its report, the commission set out a number of ways pharmacists can contribute to tackling antimicrobial resistance.

For community pharmacists, a good first step is to use dispensing software to understand the antimicrobial use patterns of your community.

Other strategies include clarifying the indication and intended duration of any antimicrobial when conducting a MedsCheck and engaging in a discussion with the patient and/or prescriber if the patient has been on an antimicrobial for an extended period.

It could also be helpful to display posters with patient care information in the pharmacy, such as how to prevent UTIs, and to highlight vaccinations service during cold and flu season with reminders about why antimicrobials should not be used for viral infections.

Hospital pharmacists have an opportunity to assess whether the antimicrobial prescriptions they see follow guidelines and, if not, to engage in discussions with prescribers in instances where patients are treated for conditions such as asymptomatic bacteriuria with antibiotics.

Another practical example is to determine the most common antimicrobial prescribed for UTIs and to develop a quality improvement project to address inappropriate use.

‘We’re increasingly seeing incidents where alert fatigue has been identified as a contributing factor. It’s not that there wasn’t an alert in place, but that it was lost among the other alerts the clinician saw,’ Prof Baysari says.

‘We’re increasingly seeing incidents where alert fatigue has been identified as a contributing factor. It’s not that there wasn’t an alert in place, but that it was lost among the other alerts the clinician saw,’ Prof Baysari says.

Beyond the arrhythmia, AF often signals broader pathological processes that impair cardiac function and reduce quality of life and life expectancy.5 Many of these conditions are closely linked to social determinants of health, disproportionately affecting populations with socioeconomic disadvantage. Effective AF management requires addressing both the arrhythmia and its underlying contributors.4

Beyond the arrhythmia, AF often signals broader pathological processes that impair cardiac function and reduce quality of life and life expectancy.5 Many of these conditions are closely linked to social determinants of health, disproportionately affecting populations with socioeconomic disadvantage. Effective AF management requires addressing both the arrhythmia and its underlying contributors.4  C – Comorbidity and risk factor management

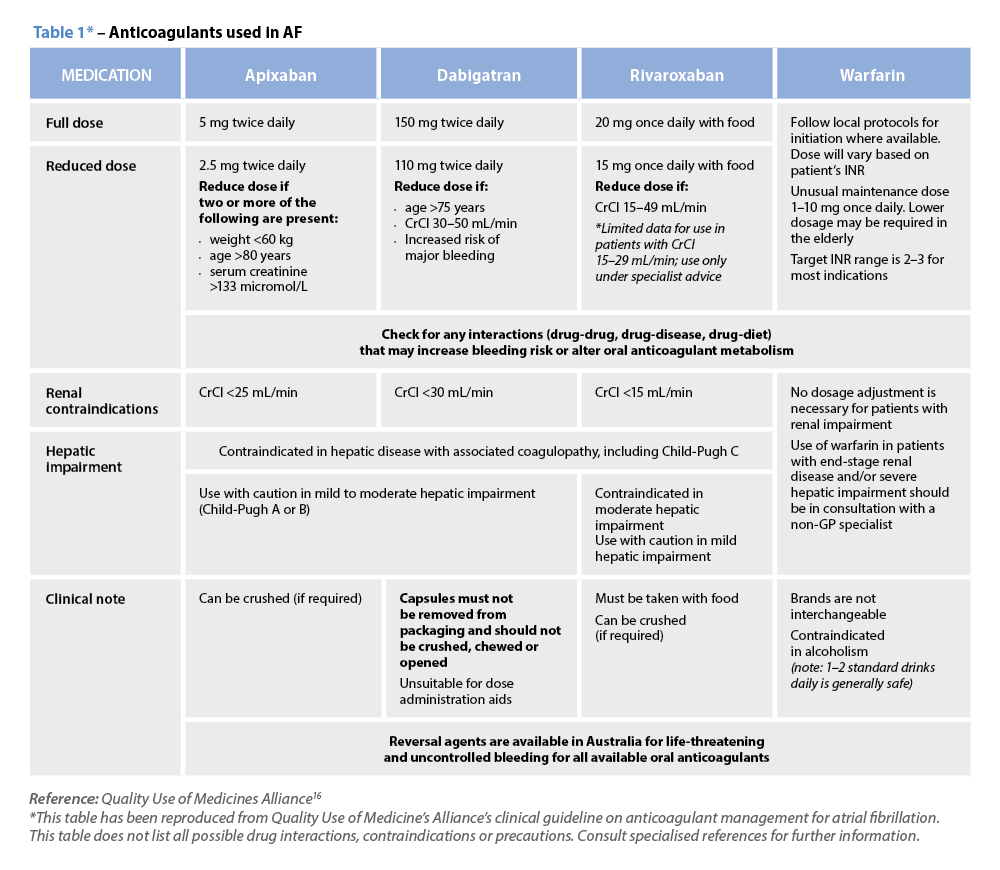

C – Comorbidity and risk factor management Warfarin

Warfarin