td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 30306

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-08-13 13:16:33

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-08-13 03:16:33

[post_content] => Pharmacist prescribing is emerging as a powerful extension of primary care in Australia – one that has the potential to improve access, enhance patient outcomes and reshape the profession.

For patients, it means timely, evidence-based treatment without the long waits often associated with GP appointments. For pharmacists, it represents an opportunity to practise to full scope, strengthen professional relationships and deliver care with immediacy and depth.

But becoming a prescriber is not just a new credential – it’s a mindset shift, demanding confidence, competence and a willingness to explore every aspect of a patient’s life to inform safe and effective decisions.

Kate Gunthorpe MPS, a Queensland-based pharmacist prescriber who recently presented at PSA25 and received special commendation in the PSA Symbion Early Career Pharmacist of the Year award category, explained to Australian Pharmacist what budding pharmacist prescribers should expect.

Pharmacist prescribing to become standard practice

According to Ms Gunthorpe, it is no longer a question of if, but when, pharmacist prescribing will become a normal part of primary care in Australia – as it already is in other countries.

‘Our scope will continue to expand. It’s not about replacing anyone, it’s about using every healthcare professional’s skills to their fullest,’ she said. ‘Pharmacist prescribing will also bring more students into the profession, and improve job satisfaction and retention.’

For Ms Gunthorpe, becoming a prescriber was a quest to close the gap between what patients needed and what she could offer.

‘I was often the first health professional someone would see, but without the ability to diagnose and treat within my scope, I sometimes felt like I was sending them away with half the solution,’ she said. ‘Prescribing gives me the ability to act in that moment, keep care local, and make a real difference straight away.’

Patients can often wait weeks to see a GP – or avoid care altogether because it feels too hard. Pharmacist prescribing gives them another safe, qualified option, and helps to ease pressure on other parts of the health system.

‘I’ve seen people walk in with something that’s been bothering them for months, and walk out with a treatment plan in under half an hour,’ Ms Gunthorpe said. ‘For some, it’s the difference between getting treated and just living with the problem.’

From a patient perspective, the feedback on the service has been overwhelmingly positive.

‘People are often surprised that pharmacists can now prescribe, but once they experience it, they appreciate the convenience and thoroughness,’ she said. ‘Many have told me they wish this had been available years ago and I’ve already had several patients come back for other prescribing services because they trust the process.’

Evolving your practice mindset

Becoming a pharmacist prescriber is not a box-ticking exercise – it’s a mindset shift.

Pharmacists are already great at taking medication histories. Asking, ‘Do you have any allergies? Have you had this before? What medications are you taking? Have you had any adverse effects?’ is par for the course.

But effectively growing into full scope requires pharmacists to push the envelope further. Take acne management for example.

As part of standard pharmacist care, acne consultations are mainly about over-the-counter options and suggesting a GP review for more severe cases.

‘Now, [as a pharmacist prescriber], I take a full patient history – incorporating their biopsychosocial factors – to assess the severity and check for underlying causes,’ she said. ‘I can [also] initiate prescription-only treatments when appropriate. It means I can manage the condition from start to finish, rather than just being a stepping stone.’

Sometimes it can be a matter of life or death. Ms Gunthorpe recalled a case where a patient presented with nausea and vomiting. After reviewing his symptoms and social history, a diagnosis of viral or bacterial gastroenteritis didn’t quite fit. So, she probed further:

Q: ‘What do you do for work?’

A: ‘I'm an electrician.’

Q: ‘So did you work today?’

A: ‘Yeah.’

Q: ‘How was work? Anything a bit unusual happen today? Did you bump your head or anything like that?’

A: ‘I stood up in a room today and hit the back of my head so hard I've had a raging headache ever since and I feel dizzy.’

Following this interaction, Ms Gunthorpe sent the patient to the emergency department straight away.

‘If I had just provided him with some ondansetron, he could have not woken up that night,’ she said. ‘So think about how that impacted his treatment plan, just because I asked him what his occupation is.’

Encouraging patients to open up

It’s not always easy getting the right information out of patients – particularly in a pharmacy environment. So Ms Gunthorpe takes a structured approach to these interactions.

‘I say, “I'm going to ask you a few questions about your life and your lifestyle, just to let me get to know you a little bit more so we can create a unique and shared management plan for you”,’ she said.

This helps patients understand that she’s not just prying – and that each question has a purpose.

‘Then they are more than willing,’ she said. ‘Nothing actually surprises me now about what patients say to me – whether it's injecting heroin or the sexual activity they get up to on the weekend.’

Post-consultation, documentation is an equally important part of the process.

‘Everything you asked, the answers to these questions and what the patient tells you has to be documented,’ Ms Gunthorpe said. ‘If it's not documented, then it didn't happen. That's just a flat out rule.’

In other words, you will not be covered medicolegally if you provide advice and there is no paper trail.

‘I encourage you to start documenting – even if it doesn't feel like it's too important,’ she said. ‘That’s something we as a whole industry need to start doing better.’

Redesigning workflows and upskilling staff

While embracing a prescribing mindset is crucial, so is maintaining the dispensary – allowing for uninterrupted patient consultations.

‘We need to ensure our dispensary keeps running while we are off the floor,’ Ms Gunthorpe said. ‘I’ve never worried that someone will burst into the room [when I'm seeing a] GP mid-consult – so we need to create that same protected environment in pharmacy.’

Upskilling pharmacy assistants and dispensary technicians has been key to making this possible. Staff now take patient details before the consultation, manage the consult rooms, and triage patients when Ms Gunthorpe is unavailable – a role they have embraced with enthusiasm.

‘When I’m not there, they need to make appointments, explain our services, and direct patients to me when I am in consults,’ she said. ‘It’s been really satisfying for them to step into expanded roles.’

Reframing relationships with general practice

Pharmacist prescribing is not intended to replace GPs, but to create more accessible, collaborative and timely care – relying on strong relationships, shared responsibility and open communication.

‘Think of prescribing as stepping into a shared space, not taking over someone else’s. Let’s do it together, with confidence, compassion, and clinical excellence,’ Ms Gunthorpe said.

In some cases referral to a GP is necessary, particularly when additional diagnostics are required. This can cause frustration if patients pay for a consultation but leave without medicines. So strengthening GP-pharmacist relationships is essential to making the model work.

‘We want this to be a shared space where we both feel safe and respected when referring either way,’ she said. ‘If a GP is booked out for 2 weeks and a child has otitis media, we want the receptionist to be able to say, “Kate down the road has consults available this afternoon”. That’s the collaboration we’re aiming for.’

Queensland Government funding for pharmacists to undertake prescribing training remains open. For more information and to check eligibility visit Pharmacist Prescribing Scope of Practice Training Program.

[post_title] => The mindset shift that’s key to prescribing success

[post_excerpt] =>

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => open

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => the-mindset-shift-thats-key-to-prescribing-success

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2025-08-13 16:04:50

[post_modified_gmt] => 2025-08-13 06:04:50

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/?p=30306

[menu_order] => 0

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

[title_attribute] => The mindset shift that’s key to prescribing success

[title] => The mindset shift that’s key to prescribing success

[href] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/the-mindset-shift-thats-key-to-prescribing-success/

[module_atts:td_module:private] => Array

(

)

[td_review:protected] => Array

(

)

[is_review:protected] =>

[post_thumb_id:protected] => 30307

[authorType] =>

)

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 30283

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-08-11 12:10:58

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-08-11 02:10:58

[post_content] => The Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI) has made an unusual move by issuing a statement on RSV vaccination errors.

There have been numerous reports to the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) of RSV vaccines being administered to the wrong patient.

As of 13 June 2025, there have been:

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 29855

[post_author] => 2266

[post_date] => 2025-08-10 12:22:30

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-08-10 02:22:30

[post_content] => Case scenario

[caption id="attachment_29840" align="alignright" width="297"] A national education program for pharmacists funded by the Australian Government under the Quality Use of Diagnostics, Therapeutics and Pathology program.[/caption]

A national education program for pharmacists funded by the Australian Government under the Quality Use of Diagnostics, Therapeutics and Pathology program.[/caption]

At a multidisciplinary professional development event, a local GP, Dr Slotz, tells you that prescribing for patients with insomnia places her in a dilemma, as she understands the risks associated with benzodiazepine and non-benzodiazepine hypnotic use. She was wondering about any new medicines on the horizon to help aid sleep.

Learning objectivesAfter reading this article, pharmacists should be able to:

|

Insomnia is one of the most common sleep disorders worldwide, and is clinically defined according to diagnostic criteria as difficulty in falling asleep, maintaining sleep or waking up too early despite adequate opportunity to sleep, leading to next day functional impairments.1,2

In Australia, acute insomnia (symptoms ≥3 days a week but less than 3 months) affects about 30–60% of adults at any given time, with about 10–15% reporting chronic insomnia (symptoms ≥3 months).3,4 It is proposed that acute precipitants (e.g. trauma, work or financial stress) create a hyperarousal response similar to but at a lower level than the fight or flight stress response. Maladaptive behaviours then develop and, through psychological conditioning, cement the hyperarousal pattern, transitioning the condition from acute to chronic.3

The state of being ‘asleep’ or in a state of ‘arousal’ in the human body is driven by various mechanisms, including5–7:

Australian guidelines, consistent with current global guidelines, recommend that cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBTi) needs to be the first-line approach for the management of insomnia. CBTi creates sustained improvements by addressing the underlying psychological and behavioural causes of insomnia, and help patients re-establish a positive association between bed and sleep, rather than an automatic association between bed and being awake.8,9 To find out more about CBTi, see the ‘Beyond sleep hygiene’ CPD article in the September 2024 issue of Australian Pharmacist.

Pharmacological treatments for insomnia may sometimes be considered where benefits exceed possible harms. Examples may include cases where the patient is experiencing significant distress or impairment by lack of sleep during acute insomnia, and for supporting patients who do not achieve full symptom remission with CBTi.10,11

However, most pharmacological treatments are recommended only for short-term use, and should be provided alongside non-pharmacological management options for insomnia.10,12

While complex, it is important to understand the physiological basis of sleep. It has been found that there may be distinct regions and neuronal tracts in the brain that drive wakefulness or sleep.5

The propagation and maintenance of wakefulness in the brain

The medullary area in the brain receives many sensory inputs such as light increase at sunrise, clock time and alarms. These signals are then transmitted through a network referred to as the reticular activating system (RAS), which extends from the medullary to the hypothalamic area. It is proposed that glutamatergic firing in the RAS actions wakefulness signals after receipt of the above sensory inputs.5,13,14 The RAS then sends signals to the basal forebrain, hypothalamus and thalamus.

The hypothalamus houses neurons that produce neuropeptides called orexin A and B, which were discovered in 1998, and represent one of the most exciting discoveries in sleep medicine.5,13–15 Orexin-producing neurons help us stay awake and alert, especially when we really need to focus, which is critical for survival.5,14 These neurons reach out to many brain areas that use other wakefulness messengers such as acetylcholine, dopamine, histamine, serotonin and noradrenaline. These areas ‘talk back’ to the hypothalamus, to further boost wakefulness signals.5 Similarly, the thalamus is an important region that also serves to relay wakefulness signals from the RAS.5

The hypothalamus houses neurons that produce neuropeptides called orexin A and B, which were discovered in 1998, and represent one of the most exciting discoveries in sleep medicine.5,13–15 Orexin-producing neurons help us stay awake and alert, especially when we really need to focus, which is critical for survival.5,14 These neurons reach out to many brain areas that use other wakefulness messengers such as acetylcholine, dopamine, histamine, serotonin and noradrenaline. These areas ‘talk back’ to the hypothalamus, to further boost wakefulness signals.5 Similarly, the thalamus is an important region that also serves to relay wakefulness signals from the RAS.5

The basal forebrain has a key role relaying signals from the RAS, stimulating cortical activity which allows for decision making and functioning while awake.5 Neurotransmitters in the basal forebrain include both glutamate and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA).5

Sleep onset and maintenance

The ventrolateral pre-optic (VLPO) area in the hypothalamus has a dense network of neurons such as GABA, galanin and others which can inhibit activity in brain regions involved in wakefulness and thus promote sleep. The ‘quietening down’ effect of the VLPO is switched on by increased melatonin levels (triggered by dimmer lighting in the evening) and other sleep-promoting messengers like prostaglandins and adenosine.5,14

Overall, selective glutamatergic and GABAergic firing determines the state of being awake or asleep.14 This reciprocal circuitry between brain arousal and sleep centres was thought to maintain a ‘flip-flop’ switch (i.e. either one is in a state of sleep or is awake).

However, it is now understood, particularly from animal studies, that there may be local brain areas in a sleep/wake state different to the rest of the brain.16,17

The most common class of sedatives in practice includes benzodiazepines and non-benzodiazepine hypnotics, which have dominated insomnia treatment over the last 5 decades. These medicines potentiate the GABAergic inhibition at GABAA receptors within the VLPO to induce sleep.18 While effective at treating insomnia symptoms, their use is limited by serious adverse effects, including anterograde amnesia, hangover sedation, dependence, tolerance, and risk of falls and fractures. This especially limits use long-term and in older patients.18–20 Benzodiazepines mainly increase the lighter stages (e.g. phase N2) in the sleep cycle, despite increasing total sleep time and reducing latency to fall asleep.21

Non-benzodiazepine hypnotics, such as zolpidem and zopiclone were later marketed and work on the same receptor sites as conventional benzodiazepines, despite their non-benzodiazepine structure.18 These medicines, considered to have specificity for certain GABAA receptor sub-types (e.g. zolpidem is specific for alpha-1 GABAA receptor sub-types) and a lower addiction potential, nonetheless have an adverse effect profile similar to the classic benzodiazepines. Zolpidem has been implicated to have a range of unusual adverse effects, including parasomnias, amnesia and hallucinations, and has generated much publicity.20

Melatonin was developed for therapeutic use in insomnia. However, studies have been disappointing and have not shown efficacy in managing insomnia symptoms except for small scale effects in older adults (>55 years) and in children with sleep disturbances linked with neurodevelopmental disorders.22–24

A range of antidepressants and antipsychotics have often been used off-label as they can antagonise monoaminergic neuromodulators that potentiate wakefulness, but evidence for their use in treating insomnia is not robust.25 Their impact on a range of receptors also makes users of these medicines more prone to adverse effects.25 Many antidepressants used ‘off-label’ for sleep, such as tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and selective noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) also decrease rapid eye movement (REM) sleep (important for memory storage and consolidation).26 In addition, SSRIs and SNRIs tend to activate the arousal system and may contribute to sleep fragmentation.

Similarly, sedating antihistamines commonly sought from pharmacies, are only effective short term, as tolerance to their sedative effects develop quite quickly. Direct evidence of their efficacy in insomnia in clinical trials is also scarce.27

They can also block other monoaminergic receptors in the brain, hence requiring the need for caution in their use due to a broad range of adverse effects.27

Given cortical hyperarousal is one of the pathophysiological causes of insomnia,3 the discovery of orexin and its potent role in the maintenance of wakefulness has fuelled drug development in this area.

Dual orexin receptor antagonists

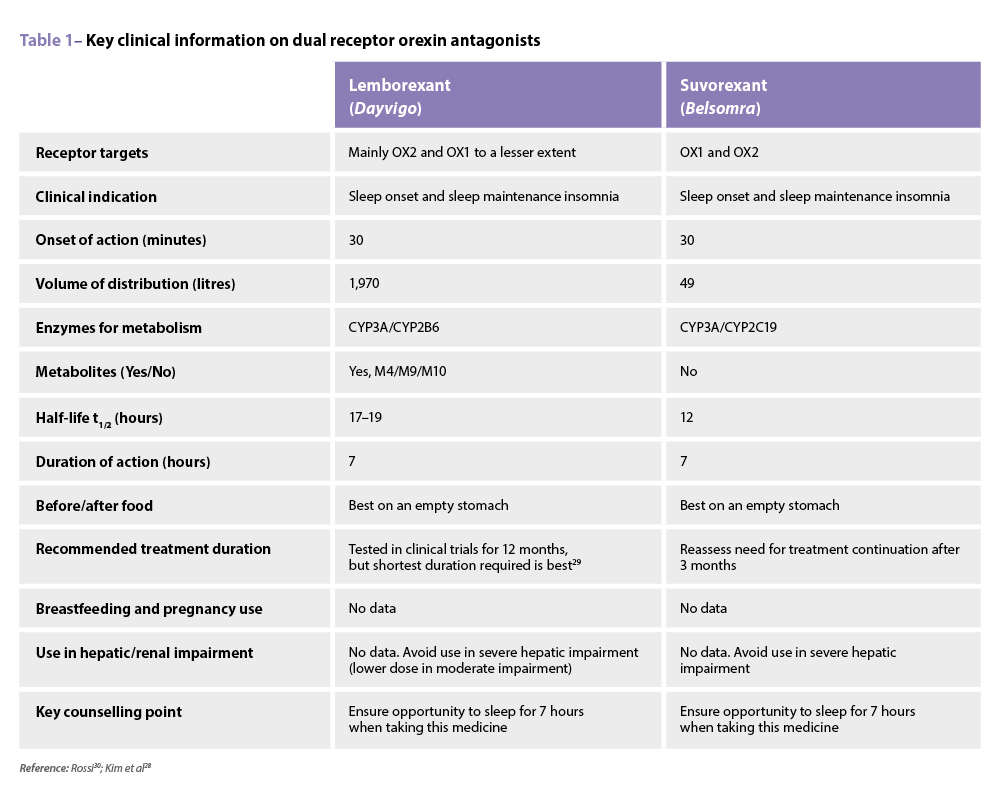

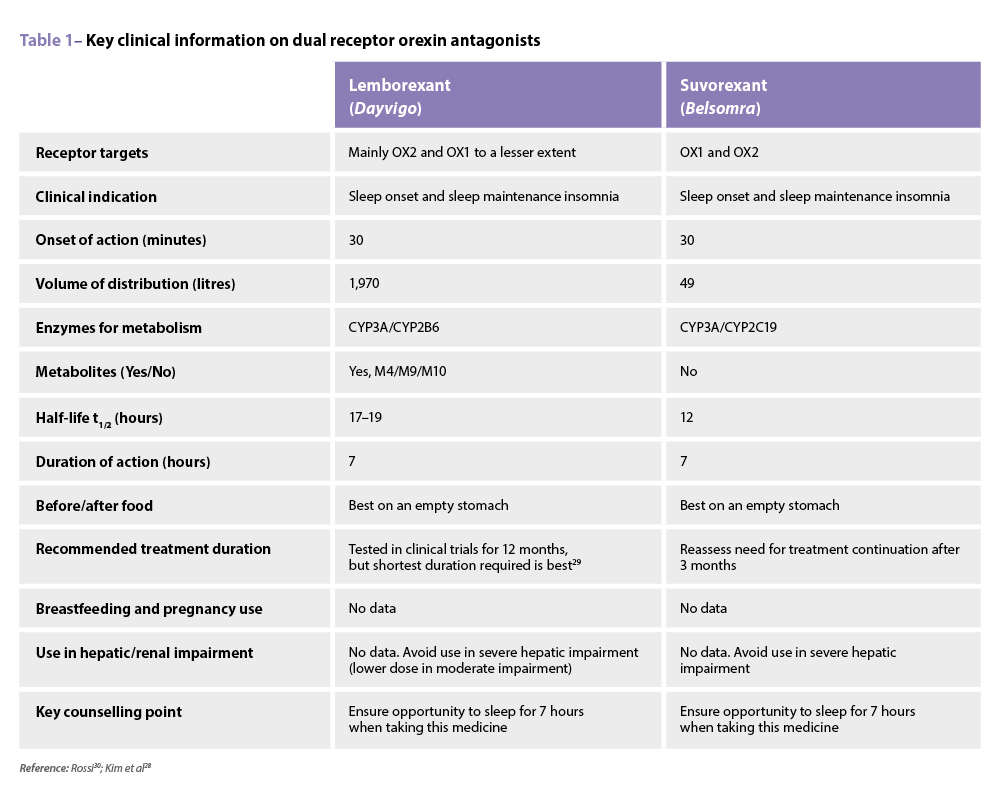

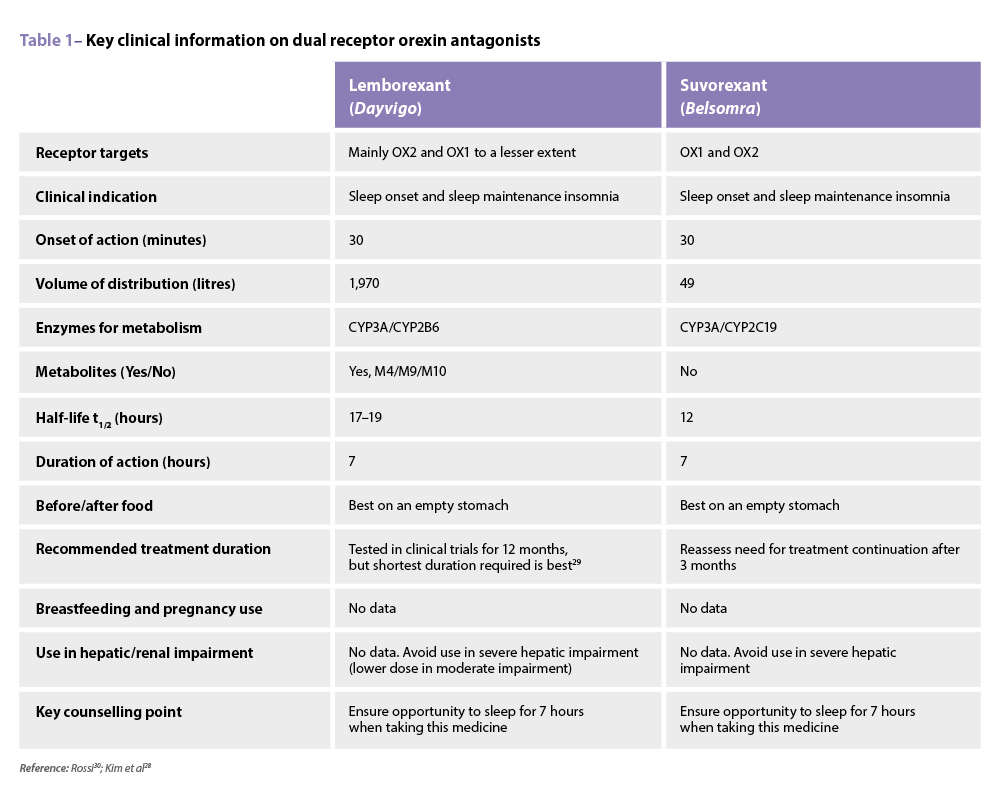

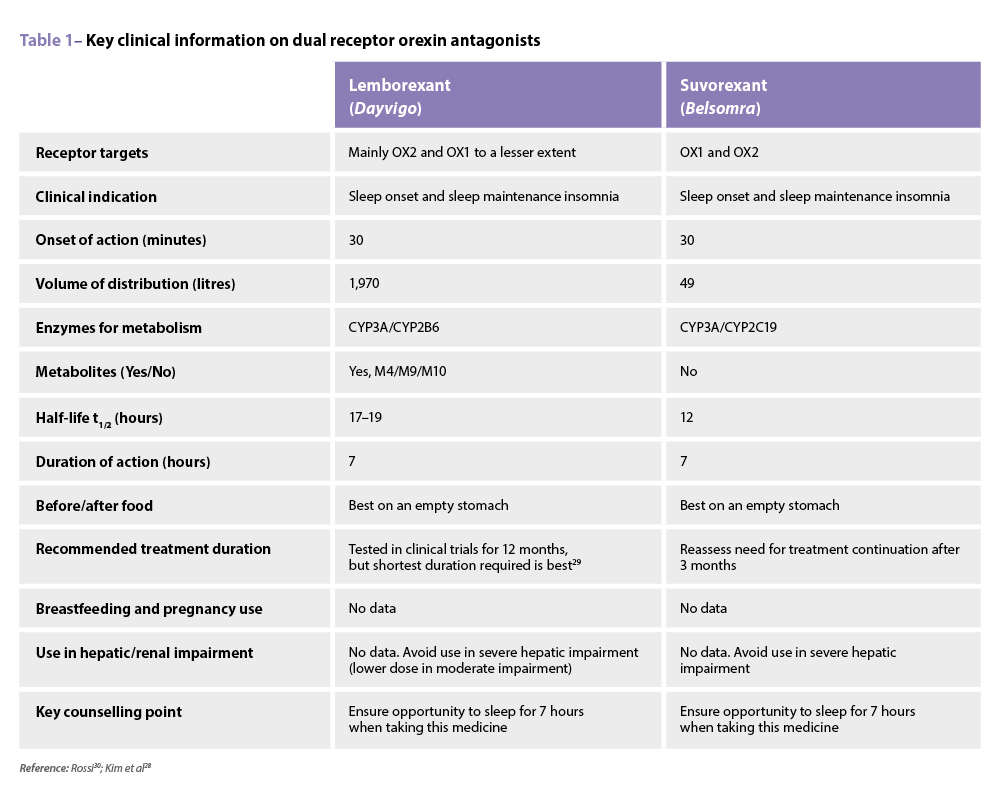

Orexin A and orexin B are two neuropeptides derived from the same precursor and act on orexin 1 (OX1) and orexin 2 (OX2) receptors (orexin A binds equally to OX1 and OX2 receptors, while orexin B has higher selectivity for OX2 receptors).28 The properties of these medicines are highlighted in Table 1.

Another dual orexin receptor antagonist (DORA), vornorexant*, is under development and currently undergoing clinical trials.28

Another dual orexin receptor antagonist (DORA), vornorexant*, is under development and currently undergoing clinical trials.28

Daridorexant* is available overseas for sleep onset and sleep maintenance insomnia, but is not currently available in Australia.28

DORAs are believed to lead to lower risk of cognitive and functional impairment when compared to GABA modulators.28 Results from human and animal studies also highlight that DORAs enable easier arousability from sleep.31–33 Hangover sedation also appears less likely compared to some benzodiazepines, especially for suvorexant.28

Real-world post-marketing data from spontaneous drug reporting in Japan indicates that DORAs have a more favourable safety profile and lower incidence of adverse events, particularly for functional impairment leading to accidents or injuries,34 and appear less likely to lead to dependence.35,36

Compared to medicines such as benzodiazepines, DORAs appear to minimally impact natural sleep architecture, mainly only increasing REM sleep periods.37 DORAs are also being tested across a range of trials for their role in improving dementia outcomes, possibly through sleep related improvements.38

DORAs are contraindicated in narcolepsy (as this condition stems from orexin deficiency). In addition, they are associated with adverse effects such as headaches, sleepiness, dizziness and fatigue. Rarely, abnormal dreams, sleep paralysis, hallucinations during sleep or possible suicidal ideation may occur.39 Combining DORAs with alcohol or other sedatives can increase the risk of adverse effects and should be avoided.10

Comparative trials directly comparing the impact of DORAs with benzodiazepines and other sedatives are relatively lacking, and the effect of DORAs on overall sleep parameters, such as total sleep time or hastening sleep onset, may be lower than that of benzodiazepines.39 However, they appear to have a more favourable safety profile.

In summary, further research and clinical experience in Australia is needed before DORAs are routinely recommended for use in insomnia.10

Single orexin receptor antagonists

Besides DORAs, research is looking at developing single orexin receptor antagonists (SORAs). OX1 receptor binding to orexin signals high potency awake states and suppression of restorative deep sleep. OX1 receptors are also associated with reward-seeking behaviour.

OX2 binding of orexin results in specific suppression of REM sleep and seems critical for wake-promoting effects of orexin.28 Hence, OX2 selective single orexin receptor antagonists (2-SORAs) are being tested (seltorexant*, in phase III clinical trials) for more tailored treatment of insomnia.28

GABAA receptor positive allosteric modulators

To overcome some of the issues associated with classic benzodiazepines, newer GABAA receptor positive allosteric modulators such as lorediplon* and EVT-201* (partial allosteric modulator at GABAA) are under investigation.28,40

Other medicines such as dimdazenil* (partial positive allosteric modulator at GABAA specific to alpha-1 and alpha-5 GABAA receptor subtypes)41 and zuranolone* (positive allosteric modulator for GABAA) have also been tested, with positive outcomes in trials. Zuranolone* is marketed overseas specifically for postnatal depression, but clinical trials for its use in insomnia are ongoing.40

Other medicines such as dimdazenil* (partial positive allosteric modulator at GABAA specific to alpha-1 and alpha-5 GABAA receptor subtypes)41 and zuranolone* (positive allosteric modulator for GABAA) have also been tested, with positive outcomes in trials. Zuranolone* is marketed overseas specifically for postnatal depression, but clinical trials for its use in insomnia are ongoing.40

Synthetic melatonin receptor agonists

Synthetic melatonin receptor agonists target melatonin 1 and 2 receptors (MT1 and MT2) and show some promise of clinical benefit in insomnia symptoms with reasonable tolerability and safety.42 This class of medicines include28,30,42,43:

Other medicines

Several 5HT2A antagonists have been trialled, such as eplivanserin*, which demonstrated positive insomnia outcomes, but did not meet the regulatory benefits versus risks criteria when proposed for registration in the US.44

There are some trials being conducted with nociceptin/orphanin FQ Receptor (NOP) agonists (e.g. sunobinop*, a partial agonist of NOP). Animal and some minimal human studies indicate that these medicines can increase non-REM sleep and reduce REM sleep.45

*Not approved in Australia

Pharmacists are often asked about new medicines as they become available. Remaining up to date with novel and emerging treatments in sleep health, while reinforcing CBTi as the recommended ‘first-line’ treatment for insomnia, can ensure pharmacists provide the most current advice in this area.

The field of sleep research and drug discovery is rapidly expanding, with a range of medicines working on various elements of the sleep-wake circuitry in the brain now available. Currently, the most promising emerging categories of sedatives with comparatively safer profiles compared to benzodiazepines are the orexin receptor antagonists and synthetic melatonin receptor agonists. However, research and clinical development is ongoing for many of these novel and emerging treatments.

Case scenario continuedYou advise Dr Slotz that orexin receptor antagonists are showing promise. Although suvorexant and lemborexant are available in Australia, you advise that research into this medicine class is ongoing and currently there is limited clinical experience with their use in Australia. When pharmacological treatment is indicated, you discuss taking into consideration the specific insomnia symptoms of patients and individual characteristics in order to specifically tailor their pharmacotherapy. You also talk about other novel and emerging treatments and highlight that research to develop new treatments for insomnia is rapidly evolving. Finally, you emphasise that CBTi is well established as a first-line treatment for insomnia, with an increasing trend of health professionals training to deliver CBTi in primary care. |

Professor Bandana Saini (she/her) BPharm, MPharm (Pharmaceutics), MBA (International Business), PhD (Pharmacy), Grad Cert Ed Studies (Higher Education), Grad Imple Sci, MPS is an academic and community pharmacist with over 2 decades of experience in sleep and respiratory health services research. She is an asthma educator and trained as a sleep technician. She also holds qualifications in management, education and implementation science.

Rose-marie Pennisi (she/her) BPharm, MBA, MPS

[post_title] => Emerging treatments for insomnia [post_excerpt] => The field of sleep research and drug discovery is rapidly expanding, with a range of medicines working on various elements of the sleep-wake circuitry in the brain now available. [post_status] => publish [comment_status] => open [ping_status] => open [post_password] => [post_name] => emerging-treatments-for-insomnia [to_ping] => [pinged] => [post_modified] => 2025-08-13 16:03:00 [post_modified_gmt] => 2025-08-13 06:03:00 [post_content_filtered] => [post_parent] => 0 [guid] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/?p=29855 [menu_order] => 0 [post_type] => post [post_mime_type] => [comment_count] => 0 [filter] => raw ) [title_attribute] => Emerging treatments for insomnia [title] => Emerging treatments for insomnia [href] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/emerging-treatments-for-insomnia/ [module_atts:td_module:private] => Array ( ) [td_review:protected] => Array ( [td_post_template] => single_template_4 ) [is_review:protected] => [post_thumb_id:protected] => 30291 [authorType] => )td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 29863

[post_author] => 1925

[post_date] => 2025-08-08 10:00:48

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-08-08 00:00:48

[post_content] => How pharmacists are trained to deal with life-threatening calls – from medicine misadventure to ingestion of pesticides.

An average of more than 550 calls a day are taken – largely by pharmacists – at Australia’s four Poisons Information Centres (PICs). That’s more than 200,000 calls a year.

Exposures to medicine, chemicals, household products, bites, stings and plants account for the majority of calls to PICs – about 80%. The remaining 20% are largely medicine-related queries. Over the past 2 years, seven of the top 10 most common substance exposures have been medicines.

The PICs are separate state organisations that work together to support the 24-hour Poisons Hotline (131126). One quarter of the PIC calls received overall are from health professionals. These include paramedics, nurses, emergency department (ED) and intensive care unit (ICU) doctors, general practitioners (GPs), mental health professionals and pharmacists. Operating with extended opening hours, the NSW PIC is the largest. It takes half the national calls. In 2024 that was over 117,000.

According to its Senior Pharmacist Poisons Information, Genevieve Adamo MPS, most poisonings are accidental.

‘However, 17% of our calls relate to deliberate self-poisoning,’ she says.

‘These are usually our most serious cases because of the large amount and the combinations taken. We also advise on therapeutic errors, recreational and occupational exposures. We encourage pharmacists to call the PIC about any exposure, particularly deliberate ingestions. If a patient has collapsed or is not breathing, we advise them to call 000 and start cardiopulmonary resuscitation. The PIC will transfer calls to 000 if necessary.’

Most Specialists in Poisons Information (SPIs) in Australia are pharmacists. SPIs perform an individual risk assessment for each case – taking a detailed history, including patient details, the substance exposure, dose/amount, time and type of exposure, symptoms and signs.

For cases already assessed by a health professional, the clinical assessment including any investigations or treatments already carried out, is also considered. All of these factors influence the risk assessment and management plan.

The PIC has access to several specific toxicology resources. These include Therapeutic Guidelines, the National Poisons Register, POISINDEX and Toxinz.

As many exposures involve medicines, resources such as the Australian Medicines Handbook (AMH) and the Monthly Index of Medical Specialities (MIMS) are also used.

‘Information on the risk of toxicity from various exposures relies on publication from actual poisonings – not clinical trials – so there may not be published answers for all clinical scenarios,’ says Ms Adamo. ‘We must consider available evidence, first principles and theoretical risks when formulating an individual management plan for each case.’

Finding the required information, and quickly collating it into an individualised risk assessment and management plan, requires training and practice, she says.

‘We look for pharmacists with a sound knowledge of pharmacology and pharmacokinetics, relevant clinical experience and excellent communication skills. In NSW the PIC internal training program consists of 12 bespoke modules, including toxidromes (toxic syndromes), communication, pesticides, household chemicals, toxicology of specific drugs and drug classes, toxinology and plant toxicology.

‘Along with the theory, trainee SPIs will listen to real-time calls and then progress to supervised call-taking after completing the bulk of the training. The trainee will complete a written exam before they can be rostered to take calls with a “buddy”.

‘Each SPI is required to pass a second exam before they are eligible to work independently and be rostered to the more complex and busy overnight shifts. This whole process usually takes 6 months.

‘The demands of the role,’ says Ms Adamo, ‘require a degree of resilience to cope with the prevalence of self-harm, along with patience to deal with often distressed and sometimes argumentative callers. Most SPIs agree these demands are outweighed by the professional rewards of working in such a clinically interesting and challenging area.’

SPIs are supported by a team of clinical toxicologists, medical specialists who consult on serious life-threatening poisonings, and provide ongoing education and research opportunities for SPIs.

AP spoke to two PIC pharmacists.

Case 1

Kristy Carter (she/her)

Kristy Carter (she/her)

Specialist in Poisons Information, NSW Poisons Information Centre

Around midday, I answered the phone to an emergency doctor who was managing a toddler inadvertently given a 10-fold dose of risperidone liquid earlier that morning and the previous morning.

The child was noticeably drowsy the day before, had slept longer than normal overnight and, after another dose that morning, had become agitated, restless and experienced a dystonic episode with abnormal head posturing and eyes deviating upwards. My colleague mentioned speaking to paramedics earlier that day about the child and promptly referred the child to hospital.

Once in hospital, the child appeared more alert, and the dystonic reaction settled. The doctor on the phone to me requested advice on management and monitoring. I advised the doctor about the clinical effects anticipated with the dosing error and when benzatropine was appropriate. This was a particularly concerning overdose in a child. Clinical effects included central nervous system (CNS) depression, dystonic reactions and anticholinergic effects such as tachycardia, agitation, restlessness and urinary retention.

Uncommon abnormalities included QT prolongation, hypotension and seizures. We discussed monitoring periods and what other investigations were needed. I encouraged them to call back if there was any deterioration or changes, particularly if there were further dystonic reactions.

Within an hour, the emergency doctor called back to report the cervical and ocular dystonias had returned – as well as new opisthotonos. The child was becoming very distressed. We discussed benzatropine dosage and when to use pro re nata (PRN) dosing overnight. The toddler had a good response to the initial dose and was discharged the next day with extra education around dosing provided to the caregivers.

The NSW Poisons Information Centre (PIC) has received many calls regarding 10-fold risperidone errors. Between September 2023 and September 2024, there were 25 cases of at least 10-fold risperidone liquid dosing errors in children aged 3–14 years.

This was particularly alarming, given paediatric patients are more susceptible to the adverse effects of risperidone. Even the smallest overdose can cause serious symptoms. We identified these errors as being mainly due to misunderstanding of dosing instructions and incorrect use of the provided dosing syringe. We knew that increasing awareness and reporting was needed to prevent further poisonings.

The NSW PIC reported these cases to the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). As a result, there have since been mandatory updates to the Product Information and Consumer Medicines Information for risperidone liquid products. The revision includes clearer dosing instructions and illustrations to help ensure correct dosing.

A public safety alert and medicines safety update were both published by the TGA in May 2025. This case is a reminder of one of the roles that pharmacists can play in medication safety and the role of PICs in identifying and preventing medicine errors.

Case 2

Louise Edwards (she/her)

Louise Edwards (she/her)

Specialist in Poisons Information, WA Poisons Information Centre

I received a call about an adult family member, who had been discovered drowsy with evidence he’d had one large vomit with a strong smell. He would not reveal what he had ingested.

The caller reported that the man had drunk a large amount of alcohol earlier in the day.

In his room, the family found empty packets of paracetamol, quetiapine, ibuprofen, and a bottle of a pesticide containing chlorpyrifos, suggesting a deliberate self-poisoning.

To help identify the ingredient in the pesticide (chlorpyrifos), I referred to the National Poisons Register. For the other substances, I referred to the Toxicology Handbook, Micromedex and Toxinz, which allowed me to understand the time of onset to symptoms, time required to monitor, possible clinical outcomes (given the unknown number of tablets in each case), and details of antidotes used in organophosphate poisoning. I also referred to the WAPIC Medical Assessment Guidelines to remind myself of local protocols.

Because the patient was still conscious and breathing, I advised the caller to get him to hospital by ambulance. I also advised them to take the tablet packets so the doctors there could work out how many might have been ingested. I also managed a call from ambulance personnel once they arrived to assist the patient. The ambulance journey to the hospital was only 10 minutes, and with no further signs of significant toxicity, there was no requirement for the patient to be transferred to a clinical toxicologist.

First responders/health professionals often experience concern about their own exposure when there are strange chemicals involved. I advised that in this case, the smell from hydrocarbons in the vomit, and potential future vomits, was not a significant risk, as long as they followed appropriate protocols to reduce the possibility of minor symptoms.

A call from the hospital before the patient’s arrival included similar concerns about “off-gassing”. I repeated the advice I had given the ambulance staff. I also advised them to call us back to be transferred to our on-call clinical toxicologist (local WAPIC protocol guidelines) once the patient had been assessed.

Usually, if it had been only the ingested pharmaceuticals, I would have advised on the assessment of paracetamol blood levels and liver function test results for considering N-acetyl cysteine (NAC), advised on potential symptoms, time required to monitor, important screening and other tests regarding quetiapine and ibuprofen, including the risk of seizures and coma with quetiapine, and the additive risk of CNS depression with alcohol and quetiapine.

In this case, the clinical toxicologist would have covered these points in their own advice, given they needed to also assess and advise the doctor about the chlorpyrifos exposure.

The hospital later called me to speak with the clinical toxicologist. I took initial details, such as that the patient was GCS 14, chest clear, managing airways, no further gastrointestinal symptoms or evidence of further bodily secretions, or other features of cholinergic toxidrome.

The patient received NAC for paracetamol and assumed small chlorpyrifos ingestion.

Among other lessons learned in this incident was the importance of providing information about off-gassing risk to ensure a potential patient receives timely support.

[post_title] => On the ground with poisons information specialists

[post_excerpt] => How pharmacists are trained to deal with life-threatening calls – from medicine misadventure to ingestion of pesticides.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => open

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => life-as-a-poisons-information-specialist

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2025-08-11 14:58:42

[post_modified_gmt] => 2025-08-11 04:58:42

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/?p=29863

[menu_order] => 0

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

[title_attribute] => On the ground with poisons information specialists

[title] => On the ground with poisons information specialists

[href] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/life-as-a-poisons-information-specialist/

[module_atts:td_module:private] => Array

(

)

[td_review:protected] => Array

(

)

[is_review:protected] =>

[post_thumb_id:protected] => 30280

[authorType] =>

)

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 30197

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-08-06 14:21:58

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-08-06 04:21:58

[post_content] => Vaccination is one of the most cost-effective and life-saving health interventions, saving over 150 million lives worldwide in the last half century.

In Australia, we’re lucky enough to have enhanced vaccination access via the National Immunisation Program (NIP).

Between 2005 and 2015, the overall burden of illness, disability and premature death from the 17 vaccine-preventable diseases covered under the NIP fell by 30%.

Yet since the COVID-19 pandemic, vaccination rates have continued to drop – particularly in vulnerable groups.

Pharmacist immunisers, who have recently become significant contributors to Australia’s vaccination effort, now have a unique opportunity to build on this success and turn things around, David Laffan – Assistant Secretary, Immunisation Access and Engagement at the federal Department of Health, Disability and Ageing – told delegates at PSA25 last week.

‘Pharmacies in Australia have provided over 13% of all vaccinations administered in 2024–25 – and a double-digit share of many of them,’ he said.

Here, Australian Pharmacist highlights the impact pharmacists have had on vaccination rates, and where we can grow even further.

Record number of COVID-19 vaccinations administered by pharmacists

The two largest vaccinations by volume provided by pharmacies are influenza and COVID-19, Mr Laffan said.

While COVID-19 vaccination rates in the general population remain low – with only 9% coverage over the past 12 months – pharmacists have administered a substantial proportion of those doses.

‘Vaccination rates in June 2025 for the COVID-19 Vaccination in Community Pharmacy (CVCP) Program were the highest they've been since the first half of 2023,’ he said.

Pharmacists overtake GPs as aged care vaccinators

Pharmacists have played a significant role in increasing vaccination rates for aged care residents, who are particularly vulnerable to severe complications, hospitalisation and death.

‘This year, 59% of residents over the age of 75 received a COVID-19 dose in the last 6 months, a big increase from less than 40% a year ago,’ Mr Laffan said.

In May this year, pharmacists delivered over 41% of COVID-19 vaccinations in residential aged care homes, compared to 38% administered by GPs.

‘So for the first time, pharmacists have provided more COVID-19 vaccines in residential aged care than general practitioners,’ he said.

While co-administration of COVID-19 and influenza vaccines has been encouraged, it has not been enthusiastically embraced by the public.

‘This winter, only about one in four COVID-19 and flu vaccines were co-administered,’ Mr Laffan said. ‘So there's also an opportunity there.’

Come November, when the new Aged Care Act will commence, offering COVID-19 and influenza vaccines will become a registration requirement.

‘Aged care providers will also be required to offer their residents shingles and pneumococcal vaccines if they're eligible under the NIP.’

RSV vaccination program heralded a success

The new maternal RSV program, launched in February 2025, has had strong uptake – significantly reducing the burden of disease.

‘Early data indicates about 60% of pregnant women are accessing the maternal vaccine and about a further 20% accessing the monoclonal antibody offered by the states and territories after birth,’ Mr Laffan said.

Maternal immunisation reduces the risk of severe RSV disease in infants under 6 months of age by around 70%.

‘These immunisations being made available through the RSV program are estimated to keep 10,000 infants out of hospital each year, and we've already seen a 40% reduction in RSV notifications for young children since the introduction of the [the program],’ he said. ‘That's an incredible success.’

Concerning fall in vaccination rates across age groups

Despite these recent successes, immunisation rates for many vaccines are low or falling. In fact, every childhood vaccine on the NIP schedule has lower uptake in 2024 than 2020.

‘This decline means that this year, there will be an additional 15,000 babies unvaccinated compared to pre-COVID immunisation rates,’ Mr Laffan said.

Mistrust, fuelled by misinformation and disinformation, has contributed significantly to vaccine hesitancy.

And it’s not childhood vaccination rates that are in decline. The preliminary findings from the National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance’s annual immunisation coverage report found that adolescent vaccination rates are also particularly low.

‘For example, only 70% of children turning 17 have received a meningococcal vaccination in 2024,’ he said.

‘Older people are at high risk of infection and serious illness, yet only a third are vaccinated for shingles and less than half are vaccinated for pneumococcal.’

The rates of vaccination in First Nations’ children are even lower in the 1 year and 2 year old cohorts. Similarly, human papillomavirus coverage rates are declining – except for a spike in 2022–23 caused by the move to a single-dose schedule.

‘There is a significant opportunity for community pharmacy to assist in lifting these rates,’ Mr Laffan added.

NIPVIP could be the saving grace

The NCIRS interim report highlighted that key barriers to vaccination uptake in children include difficulty of access and cost.

Since its inception on 1 January 2024, the National Immunisation Program Vaccinations in Pharmacy is helping to break down these barriers.

‘Opening up NIP vaccines to community pharmacies has been a really important step in improving equity,’ Mr Laffan said.

‘The NIPVIP program has improved access by enabling community pharmacies to significantly increase the number of sites that can vaccinate. In turn, consumers benefit from the convenience of your locations. This also further represents an area of significant growth potential.’

NIPVIP vaccinations are up almost 50% from 2024, demonstrating the capacity for growth for pharmacy vaccinations.

‘[In] NIPVIP’s first month of operation, pharmacies claimed 1,400 vaccination services,’ he said. ‘Since then, nearly 34 million vaccinations have been provided and over 4,750 pharmacies have registered for NIPVIP.’

And the NIPVIP program is only set to expand

The increase in this year's winter vaccinations are in part attributable to the uptick in NIPVIP participation – and pharmacies becoming more recognised and accepted as trusted NIP vaccination providers.

Federal Minister for Health, Disability and Ageing Mark Butler hinted that the program is set to expand when launching the National Immunisation Strategy for Australia 2025–2030 in June this year.

‘One of the goals within the strategy is to harmonise relevant workforce policies, training and accreditation across all states and territories, Mr Laffan said. ‘And part of this priority involves developing strategies to safely enable health professionals, including community pharmacists, to work to their full scope of practice, which the NIP helps to facilitate.’

The department is also working to harmonise NIPVIP and CVCP to ensure vaccination is embedded into routine primary care service delivery following Australia exiting the emergency stage of the pandemic – including aligning payment rates.

‘I know from many of my conversations with you that you are looking forward to having one less ordering system to deal with when it comes to COVID-19 vaccines, so we'll continue to harmonise the programs and look at ways to streamline systems and reduce barriers,’ he said.

Community pharmacies are recognised as providing a vital channel of access to vaccinations, with work underway to operationalise the National Immunisation strategy through a National implementation plan.

‘This plan is about collaboration across governments, sectors and communities to drive improved vaccination outcomes … to ensure that every Australian has equitable access to life-saving vaccines,’ Mr Laffan said.

‘To this end, I've invited the PSA to engage with the department about future vaccination priorities … to ensure that the profession has a say in future government considerations.’

[post_title] => Pharmacists are driving an increase in vaccination rates, says vaccine expert

[post_excerpt] =>

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => open

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => pharmacists-are-driving-an-increase-in-vaccination-rates-says-vaccine-expert

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2025-08-06 16:45:20

[post_modified_gmt] => 2025-08-06 06:45:20

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/?p=30197

[menu_order] => 0

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

[title_attribute] => Pharmacists are driving an increase in vaccination rates, says vaccine expert

[title] => Pharmacists are driving an increase in vaccination rates, says vaccine expert

[href] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/pharmacists-are-driving-an-increase-in-vaccination-rates-says-vaccine-expert/

[module_atts:td_module:private] => Array

(

)

[td_review:protected] => Array

(

)

[is_review:protected] =>

[post_thumb_id:protected] => 30215

[authorType] =>

)

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 30306

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-08-13 13:16:33

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-08-13 03:16:33

[post_content] => Pharmacist prescribing is emerging as a powerful extension of primary care in Australia – one that has the potential to improve access, enhance patient outcomes and reshape the profession.

For patients, it means timely, evidence-based treatment without the long waits often associated with GP appointments. For pharmacists, it represents an opportunity to practise to full scope, strengthen professional relationships and deliver care with immediacy and depth.

But becoming a prescriber is not just a new credential – it’s a mindset shift, demanding confidence, competence and a willingness to explore every aspect of a patient’s life to inform safe and effective decisions.

Kate Gunthorpe MPS, a Queensland-based pharmacist prescriber who recently presented at PSA25 and received special commendation in the PSA Symbion Early Career Pharmacist of the Year award category, explained to Australian Pharmacist what budding pharmacist prescribers should expect.

Pharmacist prescribing to become standard practice

According to Ms Gunthorpe, it is no longer a question of if, but when, pharmacist prescribing will become a normal part of primary care in Australia – as it already is in other countries.

‘Our scope will continue to expand. It’s not about replacing anyone, it’s about using every healthcare professional’s skills to their fullest,’ she said. ‘Pharmacist prescribing will also bring more students into the profession, and improve job satisfaction and retention.’

For Ms Gunthorpe, becoming a prescriber was a quest to close the gap between what patients needed and what she could offer.

‘I was often the first health professional someone would see, but without the ability to diagnose and treat within my scope, I sometimes felt like I was sending them away with half the solution,’ she said. ‘Prescribing gives me the ability to act in that moment, keep care local, and make a real difference straight away.’

Patients can often wait weeks to see a GP – or avoid care altogether because it feels too hard. Pharmacist prescribing gives them another safe, qualified option, and helps to ease pressure on other parts of the health system.

‘I’ve seen people walk in with something that’s been bothering them for months, and walk out with a treatment plan in under half an hour,’ Ms Gunthorpe said. ‘For some, it’s the difference between getting treated and just living with the problem.’

From a patient perspective, the feedback on the service has been overwhelmingly positive.

‘People are often surprised that pharmacists can now prescribe, but once they experience it, they appreciate the convenience and thoroughness,’ she said. ‘Many have told me they wish this had been available years ago and I’ve already had several patients come back for other prescribing services because they trust the process.’

Evolving your practice mindset

Becoming a pharmacist prescriber is not a box-ticking exercise – it’s a mindset shift.

Pharmacists are already great at taking medication histories. Asking, ‘Do you have any allergies? Have you had this before? What medications are you taking? Have you had any adverse effects?’ is par for the course.

But effectively growing into full scope requires pharmacists to push the envelope further. Take acne management for example.

As part of standard pharmacist care, acne consultations are mainly about over-the-counter options and suggesting a GP review for more severe cases.

‘Now, [as a pharmacist prescriber], I take a full patient history – incorporating their biopsychosocial factors – to assess the severity and check for underlying causes,’ she said. ‘I can [also] initiate prescription-only treatments when appropriate. It means I can manage the condition from start to finish, rather than just being a stepping stone.’

Sometimes it can be a matter of life or death. Ms Gunthorpe recalled a case where a patient presented with nausea and vomiting. After reviewing his symptoms and social history, a diagnosis of viral or bacterial gastroenteritis didn’t quite fit. So, she probed further:

Q: ‘What do you do for work?’

A: ‘I'm an electrician.’

Q: ‘So did you work today?’

A: ‘Yeah.’

Q: ‘How was work? Anything a bit unusual happen today? Did you bump your head or anything like that?’

A: ‘I stood up in a room today and hit the back of my head so hard I've had a raging headache ever since and I feel dizzy.’

Following this interaction, Ms Gunthorpe sent the patient to the emergency department straight away.

‘If I had just provided him with some ondansetron, he could have not woken up that night,’ she said. ‘So think about how that impacted his treatment plan, just because I asked him what his occupation is.’

Encouraging patients to open up

It’s not always easy getting the right information out of patients – particularly in a pharmacy environment. So Ms Gunthorpe takes a structured approach to these interactions.

‘I say, “I'm going to ask you a few questions about your life and your lifestyle, just to let me get to know you a little bit more so we can create a unique and shared management plan for you”,’ she said.

This helps patients understand that she’s not just prying – and that each question has a purpose.

‘Then they are more than willing,’ she said. ‘Nothing actually surprises me now about what patients say to me – whether it's injecting heroin or the sexual activity they get up to on the weekend.’

Post-consultation, documentation is an equally important part of the process.

‘Everything you asked, the answers to these questions and what the patient tells you has to be documented,’ Ms Gunthorpe said. ‘If it's not documented, then it didn't happen. That's just a flat out rule.’

In other words, you will not be covered medicolegally if you provide advice and there is no paper trail.

‘I encourage you to start documenting – even if it doesn't feel like it's too important,’ she said. ‘That’s something we as a whole industry need to start doing better.’

Redesigning workflows and upskilling staff

While embracing a prescribing mindset is crucial, so is maintaining the dispensary – allowing for uninterrupted patient consultations.

‘We need to ensure our dispensary keeps running while we are off the floor,’ Ms Gunthorpe said. ‘I’ve never worried that someone will burst into the room [when I'm seeing a] GP mid-consult – so we need to create that same protected environment in pharmacy.’

Upskilling pharmacy assistants and dispensary technicians has been key to making this possible. Staff now take patient details before the consultation, manage the consult rooms, and triage patients when Ms Gunthorpe is unavailable – a role they have embraced with enthusiasm.

‘When I’m not there, they need to make appointments, explain our services, and direct patients to me when I am in consults,’ she said. ‘It’s been really satisfying for them to step into expanded roles.’

Reframing relationships with general practice

Pharmacist prescribing is not intended to replace GPs, but to create more accessible, collaborative and timely care – relying on strong relationships, shared responsibility and open communication.

‘Think of prescribing as stepping into a shared space, not taking over someone else’s. Let’s do it together, with confidence, compassion, and clinical excellence,’ Ms Gunthorpe said.

In some cases referral to a GP is necessary, particularly when additional diagnostics are required. This can cause frustration if patients pay for a consultation but leave without medicines. So strengthening GP-pharmacist relationships is essential to making the model work.

‘We want this to be a shared space where we both feel safe and respected when referring either way,’ she said. ‘If a GP is booked out for 2 weeks and a child has otitis media, we want the receptionist to be able to say, “Kate down the road has consults available this afternoon”. That’s the collaboration we’re aiming for.’

Queensland Government funding for pharmacists to undertake prescribing training remains open. For more information and to check eligibility visit Pharmacist Prescribing Scope of Practice Training Program.

[post_title] => The mindset shift that’s key to prescribing success

[post_excerpt] =>

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => open

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => the-mindset-shift-thats-key-to-prescribing-success

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2025-08-13 16:04:50

[post_modified_gmt] => 2025-08-13 06:04:50

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/?p=30306

[menu_order] => 0

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

[title_attribute] => The mindset shift that’s key to prescribing success

[title] => The mindset shift that’s key to prescribing success

[href] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/the-mindset-shift-thats-key-to-prescribing-success/

[module_atts:td_module:private] => Array

(

)

[td_review:protected] => Array

(

)

[is_review:protected] =>

[post_thumb_id:protected] => 30307

[authorType] =>

)

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 30283

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-08-11 12:10:58

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-08-11 02:10:58

[post_content] => The Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI) has made an unusual move by issuing a statement on RSV vaccination errors.

There have been numerous reports to the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) of RSV vaccines being administered to the wrong patient.

As of 13 June 2025, there have been:

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 29855

[post_author] => 2266

[post_date] => 2025-08-10 12:22:30

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-08-10 02:22:30

[post_content] => Case scenario

[caption id="attachment_29840" align="alignright" width="297"] A national education program for pharmacists funded by the Australian Government under the Quality Use of Diagnostics, Therapeutics and Pathology program.[/caption]

A national education program for pharmacists funded by the Australian Government under the Quality Use of Diagnostics, Therapeutics and Pathology program.[/caption]

At a multidisciplinary professional development event, a local GP, Dr Slotz, tells you that prescribing for patients with insomnia places her in a dilemma, as she understands the risks associated with benzodiazepine and non-benzodiazepine hypnotic use. She was wondering about any new medicines on the horizon to help aid sleep.

Learning objectivesAfter reading this article, pharmacists should be able to:

|

Insomnia is one of the most common sleep disorders worldwide, and is clinically defined according to diagnostic criteria as difficulty in falling asleep, maintaining sleep or waking up too early despite adequate opportunity to sleep, leading to next day functional impairments.1,2

In Australia, acute insomnia (symptoms ≥3 days a week but less than 3 months) affects about 30–60% of adults at any given time, with about 10–15% reporting chronic insomnia (symptoms ≥3 months).3,4 It is proposed that acute precipitants (e.g. trauma, work or financial stress) create a hyperarousal response similar to but at a lower level than the fight or flight stress response. Maladaptive behaviours then develop and, through psychological conditioning, cement the hyperarousal pattern, transitioning the condition from acute to chronic.3

The state of being ‘asleep’ or in a state of ‘arousal’ in the human body is driven by various mechanisms, including5–7:

Australian guidelines, consistent with current global guidelines, recommend that cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBTi) needs to be the first-line approach for the management of insomnia. CBTi creates sustained improvements by addressing the underlying psychological and behavioural causes of insomnia, and help patients re-establish a positive association between bed and sleep, rather than an automatic association between bed and being awake.8,9 To find out more about CBTi, see the ‘Beyond sleep hygiene’ CPD article in the September 2024 issue of Australian Pharmacist.

Pharmacological treatments for insomnia may sometimes be considered where benefits exceed possible harms. Examples may include cases where the patient is experiencing significant distress or impairment by lack of sleep during acute insomnia, and for supporting patients who do not achieve full symptom remission with CBTi.10,11

However, most pharmacological treatments are recommended only for short-term use, and should be provided alongside non-pharmacological management options for insomnia.10,12

While complex, it is important to understand the physiological basis of sleep. It has been found that there may be distinct regions and neuronal tracts in the brain that drive wakefulness or sleep.5

The propagation and maintenance of wakefulness in the brain

The medullary area in the brain receives many sensory inputs such as light increase at sunrise, clock time and alarms. These signals are then transmitted through a network referred to as the reticular activating system (RAS), which extends from the medullary to the hypothalamic area. It is proposed that glutamatergic firing in the RAS actions wakefulness signals after receipt of the above sensory inputs.5,13,14 The RAS then sends signals to the basal forebrain, hypothalamus and thalamus.

The hypothalamus houses neurons that produce neuropeptides called orexin A and B, which were discovered in 1998, and represent one of the most exciting discoveries in sleep medicine.5,13–15 Orexin-producing neurons help us stay awake and alert, especially when we really need to focus, which is critical for survival.5,14 These neurons reach out to many brain areas that use other wakefulness messengers such as acetylcholine, dopamine, histamine, serotonin and noradrenaline. These areas ‘talk back’ to the hypothalamus, to further boost wakefulness signals.5 Similarly, the thalamus is an important region that also serves to relay wakefulness signals from the RAS.5

The hypothalamus houses neurons that produce neuropeptides called orexin A and B, which were discovered in 1998, and represent one of the most exciting discoveries in sleep medicine.5,13–15 Orexin-producing neurons help us stay awake and alert, especially when we really need to focus, which is critical for survival.5,14 These neurons reach out to many brain areas that use other wakefulness messengers such as acetylcholine, dopamine, histamine, serotonin and noradrenaline. These areas ‘talk back’ to the hypothalamus, to further boost wakefulness signals.5 Similarly, the thalamus is an important region that also serves to relay wakefulness signals from the RAS.5

The basal forebrain has a key role relaying signals from the RAS, stimulating cortical activity which allows for decision making and functioning while awake.5 Neurotransmitters in the basal forebrain include both glutamate and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA).5

Sleep onset and maintenance

The ventrolateral pre-optic (VLPO) area in the hypothalamus has a dense network of neurons such as GABA, galanin and others which can inhibit activity in brain regions involved in wakefulness and thus promote sleep. The ‘quietening down’ effect of the VLPO is switched on by increased melatonin levels (triggered by dimmer lighting in the evening) and other sleep-promoting messengers like prostaglandins and adenosine.5,14

Overall, selective glutamatergic and GABAergic firing determines the state of being awake or asleep.14 This reciprocal circuitry between brain arousal and sleep centres was thought to maintain a ‘flip-flop’ switch (i.e. either one is in a state of sleep or is awake).

However, it is now understood, particularly from animal studies, that there may be local brain areas in a sleep/wake state different to the rest of the brain.16,17

The most common class of sedatives in practice includes benzodiazepines and non-benzodiazepine hypnotics, which have dominated insomnia treatment over the last 5 decades. These medicines potentiate the GABAergic inhibition at GABAA receptors within the VLPO to induce sleep.18 While effective at treating insomnia symptoms, their use is limited by serious adverse effects, including anterograde amnesia, hangover sedation, dependence, tolerance, and risk of falls and fractures. This especially limits use long-term and in older patients.18–20 Benzodiazepines mainly increase the lighter stages (e.g. phase N2) in the sleep cycle, despite increasing total sleep time and reducing latency to fall asleep.21

Non-benzodiazepine hypnotics, such as zolpidem and zopiclone were later marketed and work on the same receptor sites as conventional benzodiazepines, despite their non-benzodiazepine structure.18 These medicines, considered to have specificity for certain GABAA receptor sub-types (e.g. zolpidem is specific for alpha-1 GABAA receptor sub-types) and a lower addiction potential, nonetheless have an adverse effect profile similar to the classic benzodiazepines. Zolpidem has been implicated to have a range of unusual adverse effects, including parasomnias, amnesia and hallucinations, and has generated much publicity.20

Melatonin was developed for therapeutic use in insomnia. However, studies have been disappointing and have not shown efficacy in managing insomnia symptoms except for small scale effects in older adults (>55 years) and in children with sleep disturbances linked with neurodevelopmental disorders.22–24

A range of antidepressants and antipsychotics have often been used off-label as they can antagonise monoaminergic neuromodulators that potentiate wakefulness, but evidence for their use in treating insomnia is not robust.25 Their impact on a range of receptors also makes users of these medicines more prone to adverse effects.25 Many antidepressants used ‘off-label’ for sleep, such as tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and selective noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) also decrease rapid eye movement (REM) sleep (important for memory storage and consolidation).26 In addition, SSRIs and SNRIs tend to activate the arousal system and may contribute to sleep fragmentation.

Similarly, sedating antihistamines commonly sought from pharmacies, are only effective short term, as tolerance to their sedative effects develop quite quickly. Direct evidence of their efficacy in insomnia in clinical trials is also scarce.27

They can also block other monoaminergic receptors in the brain, hence requiring the need for caution in their use due to a broad range of adverse effects.27

Given cortical hyperarousal is one of the pathophysiological causes of insomnia,3 the discovery of orexin and its potent role in the maintenance of wakefulness has fuelled drug development in this area.

Dual orexin receptor antagonists

Orexin A and orexin B are two neuropeptides derived from the same precursor and act on orexin 1 (OX1) and orexin 2 (OX2) receptors (orexin A binds equally to OX1 and OX2 receptors, while orexin B has higher selectivity for OX2 receptors).28 The properties of these medicines are highlighted in Table 1.

Another dual orexin receptor antagonist (DORA), vornorexant*, is under development and currently undergoing clinical trials.28

Another dual orexin receptor antagonist (DORA), vornorexant*, is under development and currently undergoing clinical trials.28

Daridorexant* is available overseas for sleep onset and sleep maintenance insomnia, but is not currently available in Australia.28

DORAs are believed to lead to lower risk of cognitive and functional impairment when compared to GABA modulators.28 Results from human and animal studies also highlight that DORAs enable easier arousability from sleep.31–33 Hangover sedation also appears less likely compared to some benzodiazepines, especially for suvorexant.28

Real-world post-marketing data from spontaneous drug reporting in Japan indicates that DORAs have a more favourable safety profile and lower incidence of adverse events, particularly for functional impairment leading to accidents or injuries,34 and appear less likely to lead to dependence.35,36

Compared to medicines such as benzodiazepines, DORAs appear to minimally impact natural sleep architecture, mainly only increasing REM sleep periods.37 DORAs are also being tested across a range of trials for their role in improving dementia outcomes, possibly through sleep related improvements.38

DORAs are contraindicated in narcolepsy (as this condition stems from orexin deficiency). In addition, they are associated with adverse effects such as headaches, sleepiness, dizziness and fatigue. Rarely, abnormal dreams, sleep paralysis, hallucinations during sleep or possible suicidal ideation may occur.39 Combining DORAs with alcohol or other sedatives can increase the risk of adverse effects and should be avoided.10

Comparative trials directly comparing the impact of DORAs with benzodiazepines and other sedatives are relatively lacking, and the effect of DORAs on overall sleep parameters, such as total sleep time or hastening sleep onset, may be lower than that of benzodiazepines.39 However, they appear to have a more favourable safety profile.

In summary, further research and clinical experience in Australia is needed before DORAs are routinely recommended for use in insomnia.10

Single orexin receptor antagonists

Besides DORAs, research is looking at developing single orexin receptor antagonists (SORAs). OX1 receptor binding to orexin signals high potency awake states and suppression of restorative deep sleep. OX1 receptors are also associated with reward-seeking behaviour.

OX2 binding of orexin results in specific suppression of REM sleep and seems critical for wake-promoting effects of orexin.28 Hence, OX2 selective single orexin receptor antagonists (2-SORAs) are being tested (seltorexant*, in phase III clinical trials) for more tailored treatment of insomnia.28

GABAA receptor positive allosteric modulators

To overcome some of the issues associated with classic benzodiazepines, newer GABAA receptor positive allosteric modulators such as lorediplon* and EVT-201* (partial allosteric modulator at GABAA) are under investigation.28,40

Other medicines such as dimdazenil* (partial positive allosteric modulator at GABAA specific to alpha-1 and alpha-5 GABAA receptor subtypes)41 and zuranolone* (positive allosteric modulator for GABAA) have also been tested, with positive outcomes in trials. Zuranolone* is marketed overseas specifically for postnatal depression, but clinical trials for its use in insomnia are ongoing.40

Other medicines such as dimdazenil* (partial positive allosteric modulator at GABAA specific to alpha-1 and alpha-5 GABAA receptor subtypes)41 and zuranolone* (positive allosteric modulator for GABAA) have also been tested, with positive outcomes in trials. Zuranolone* is marketed overseas specifically for postnatal depression, but clinical trials for its use in insomnia are ongoing.40

Synthetic melatonin receptor agonists

Synthetic melatonin receptor agonists target melatonin 1 and 2 receptors (MT1 and MT2) and show some promise of clinical benefit in insomnia symptoms with reasonable tolerability and safety.42 This class of medicines include28,30,42,43:

Other medicines

Several 5HT2A antagonists have been trialled, such as eplivanserin*, which demonstrated positive insomnia outcomes, but did not meet the regulatory benefits versus risks criteria when proposed for registration in the US.44

There are some trials being conducted with nociceptin/orphanin FQ Receptor (NOP) agonists (e.g. sunobinop*, a partial agonist of NOP). Animal and some minimal human studies indicate that these medicines can increase non-REM sleep and reduce REM sleep.45

*Not approved in Australia

Pharmacists are often asked about new medicines as they become available. Remaining up to date with novel and emerging treatments in sleep health, while reinforcing CBTi as the recommended ‘first-line’ treatment for insomnia, can ensure pharmacists provide the most current advice in this area.

The field of sleep research and drug discovery is rapidly expanding, with a range of medicines working on various elements of the sleep-wake circuitry in the brain now available. Currently, the most promising emerging categories of sedatives with comparatively safer profiles compared to benzodiazepines are the orexin receptor antagonists and synthetic melatonin receptor agonists. However, research and clinical development is ongoing for many of these novel and emerging treatments.

Case scenario continuedYou advise Dr Slotz that orexin receptor antagonists are showing promise. Although suvorexant and lemborexant are available in Australia, you advise that research into this medicine class is ongoing and currently there is limited clinical experience with their use in Australia. When pharmacological treatment is indicated, you discuss taking into consideration the specific insomnia symptoms of patients and individual characteristics in order to specifically tailor their pharmacotherapy. You also talk about other novel and emerging treatments and highlight that research to develop new treatments for insomnia is rapidly evolving. Finally, you emphasise that CBTi is well established as a first-line treatment for insomnia, with an increasing trend of health professionals training to deliver CBTi in primary care. |

Professor Bandana Saini (she/her) BPharm, MPharm (Pharmaceutics), MBA (International Business), PhD (Pharmacy), Grad Cert Ed Studies (Higher Education), Grad Imple Sci, MPS is an academic and community pharmacist with over 2 decades of experience in sleep and respiratory health services research. She is an asthma educator and trained as a sleep technician. She also holds qualifications in management, education and implementation science.

Rose-marie Pennisi (she/her) BPharm, MBA, MPS

[post_title] => Emerging treatments for insomnia [post_excerpt] => The field of sleep research and drug discovery is rapidly expanding, with a range of medicines working on various elements of the sleep-wake circuitry in the brain now available. [post_status] => publish [comment_status] => open [ping_status] => open [post_password] => [post_name] => emerging-treatments-for-insomnia [to_ping] => [pinged] => [post_modified] => 2025-08-13 16:03:00 [post_modified_gmt] => 2025-08-13 06:03:00 [post_content_filtered] => [post_parent] => 0 [guid] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/?p=29855 [menu_order] => 0 [post_type] => post [post_mime_type] => [comment_count] => 0 [filter] => raw ) [title_attribute] => Emerging treatments for insomnia [title] => Emerging treatments for insomnia [href] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/emerging-treatments-for-insomnia/ [module_atts:td_module:private] => Array ( ) [td_review:protected] => Array ( [td_post_template] => single_template_4 ) [is_review:protected] => [post_thumb_id:protected] => 30291 [authorType] => )td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 29863

[post_author] => 1925

[post_date] => 2025-08-08 10:00:48

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-08-08 00:00:48

[post_content] => How pharmacists are trained to deal with life-threatening calls – from medicine misadventure to ingestion of pesticides.

An average of more than 550 calls a day are taken – largely by pharmacists – at Australia’s four Poisons Information Centres (PICs). That’s more than 200,000 calls a year.

Exposures to medicine, chemicals, household products, bites, stings and plants account for the majority of calls to PICs – about 80%. The remaining 20% are largely medicine-related queries. Over the past 2 years, seven of the top 10 most common substance exposures have been medicines.