Pharmacist prescribing is ‘imminent’, says PSA National President Dr Shane Jackson. So what could that mean for you and your patients?

Pharmacists will have prescribing powers by 2020, predicts Shane Jackson.

‘Prescribing is an activity that is well within the scope of practice of a pharmacist,’ the PSA National President said.

Significant forward momentum in the bid for pharmacist prescribing powers has recently come from the Pharmacy Board of Australia calling a meeting of interested stakeholders to ‘explore opportunities for improving access to medicines through pharmacist prescribing’.

A spokesperson told Australian Pharmacist it was ‘premature for the Board to provide comment about future prescribing options for pharmacists’ but that it was ‘looking forward to participating in the forum alongside other attendees’.

The path ahead

The forum coincides with the final stages of Victoria’s 18-month trial of collaborative prescribing for pharmacists, the Chronic Disease Management Pilot.

The trial was based on a collaborative prescribing model, which typically involves an independent prescriber and pharmacist working in partnership ‘to implement an agreed patient-specific clinical management plan where doctors make the diagnosis while pharmacists prescribe according to the agreed plan’.1

Jarrod McMaugh was PSA Victoria’s nominee for the trial advisory committee.

‘The pilot involves the GP identifying a patient they feel is stable enough to be managed by the pharmacist under a specific set of instructions,’ said Mr McMaugh, Managing Partner at Capital Chemist Coburg North.

‘The GP sets out a treatment plan saying, for example, “I want you to keep the patient within this blood pressure range and if not you can step up this dose or add this prescription”.’

The trial has aimed to give appropriately trained pharmacists the opportunity to provide regular dose monitoring, dose refinement, earlier intervention and prompt referral to GPs around issues associated with chronic diseases and medication.

Mr McMaugh said that, as yet, little was known about the initial findings from the pilot. ‘The department is keeping that information close to the chest,’ he said.

‘But I do know that sites were having lots of success with patients who were willing to participate.’

Collaborative prescribing around the world

Collaborative drug therapy management (CDTM) by pharmacists was first introduced in Washington State in 1979. Now the vast majority of states in the US authorise Pharmacist Collaborative Practice Agreements, although the extent of services authorised varies greatly.

In 2003, the UK introduced pharmacist supplementary prescribing, with a specific clinical management plan for each patient, as part of its response to a dire GP shortage.

From 2005 onwards, Canadian provinces gained powers ranging from ‘dependent’ or ‘delegate’ prescribing to independent prescribing, while New Zealand pharmacists gained collaborative prescribing powers in 2013.

PSA Manager of Strategic Policy Bob Buckham is the former Chief Pharmacist Adviser to the Pharmaceutical Society of New Zealand.

He said the adoption of a collaborative model had been well received by other health professionals in New Zealand.

‘The collaborative model meant that a lot of the opposition to pharmacist prescribing could be worked through because often pharmacists had a rapport with the clinical team, which was aware of the pharmacist’s capabilities,’ he said.

‘It also helped that pharmacists over there weren’t the first non-medical prescribers – nurse practitioners and midwives were already prescribing.’

An extensive Australian review of relevant literature has concluded that a collaborative model of pharmacist prescribing could be best suited to Australia.

‘Pharmacists and pharmacy clients prefer doctors retaining their primary role in disease diagnosis,’ the review stated.1

‘This, together with a close collaboration between doctors and supplementary pharmacist prescribers, may address doctors’ concerns regarding patients’ safety while patients take advantage of the potential benefits of an expanded prescribing role for pharmacists.’

PSA National President Dr Shane Jackson agreed collaborative prescribing could be the best way forward here.

‘Collaborative prescribing is a good model and it’s probably what consumers are most comfortable with and, depending on what the individual collaborative agreement actually says, the pharmacist’s authority can be quite broad,’ he said.

Independent prescribing

Independent prescribing could offer additional benefits in future, proponents have said. Under an independent model, the pharmacist is responsible for clinical assessment and diagnosis of a patient, without the supervision of another healthcare professional.

Professor of Pharmacy at the Queensland University of Technology (QUT), Dr Greg Kyle, suggested that if the aim of pharmacist prescribing was to improve patient outcomes and streamline their healthcare journey, then working towards independent prescribing made sense.

He used medication reviews as an example. ‘At the moment, the GP says “please go and review this patient and send me a letter on what your recommendations are in terms of medication management”,’ he said.

‘The pharmacist visits them, does the review and sends recommendations back. Why couldn’t the pharmacist change those prescriptions?’

He argued pharmacists were highly trained medication managers and experts in pharmacotherapy, and should therefore be prescribing independently.

‘It would save the health system funds from an extra GP visit, it would save the patient additional delays and with My Health Record that information can be updated at the time of consultation,’ he said.

Dr Kyle pointed to successful applications of this model in some Canadian jurisdictions. In the UK, legislation enabling supplementary prescribing was expanded to give pharmacists independent prescribing authority in 2006.

Benefits for patients

Non-medical prescribing has been shown to provide faster access to medicines, and more flexible, patient-oriented care.2

In collaborative practice models it has been shown to improve patient outcomes in a range of conditions, including depression,3 pain management,4 heart disease, diabetes and asthma.1

Table 1. Pharmacist prescribing models around the world

| Country | Prescribing model | Description |

| US | Collaborative Drug Therapy Management | CDTM involves a collaborative practice agreement (CPA) between healthcare providers and pharmacists. State laws governing CPAs vary widely and can limit the types of practices, health conditions or settings pharmacist can perform delegated tasks, including prescribing.⁸ |

| Independent prescriber | Pharmacist-initiated independent prescribing of vaccines is allowed in 17 states. Oral contraception can be independently prescribed in Oregon and California.9 | |

| UK | Supplementary

prescriber |

Supplementary prescribers may prescribe any medicine (including controlled drugs), within the framework of a patient-specific clinical management plan, which has been agreed with a doctor.10 |

| Independent

prescriber |

A pharmacist independent prescriber (PIP) may prescribe autonomously for any condition within their clinical competence.11 | |

| Canada | Dependent or delegate prescribing | Many provinces allow pharmacists to prescribe for minor ailments/conditions and in an emergency. Most states allow pharmacists to change drug dosages or formulation, renew or extend prescriptions and administer a drug by injection.12 |

| Independent prescriber | Alberta allows certain authorised pharmacists to initiate Schedule 1 drug prescriptions independently.12 | |

| New Zealand | Collaborative prescribing | Pharmacist prescribers are not the primary diagnostician but they are able to write prescriptions for patients under their care, and to initiate or modify therapy. That can include stopping treatment that’s been initiated by another prescriber.13 |

Independent prescribing by pharmacists, meanwhile, has been shown to provide patient outcomes that are similar to – and sometimes better than – doctor prescribing outcomes when it comes to managing blood pressure, cholesterol and HbA1c.5

A systemic review of 46 UK and US studies found that patient adherence to medication, patient satisfaction and health-related quality of life were comparable between pharmacist prescribers and doctor prescribers.

Benefits for pharmacists

For pharmacists, the potential benefits of expanded scope of care include better job satisfaction and remuneration.

‘Pharmacist prescribing authority would allow pharmacists to apply what they’ve been trained to do at university,’ PSA’s Dr Jackson said.

‘It would reduce the expectation gap between what graduates think they’re going to do and what they do in practice.’

Dr Jackson added that allowing pharmacists to practise to their full scope could also help reduce hospital admissions due to medication errors.

‘Pharmacists are experts in medicine, so who best to prescribe than the pharmacist who has the best expertise around medicines management,’ he said.

Not a panacea

Just because some overseas pharmacists can prescribe, doesn’t mean they do, said QUT’s Dr Kyle.

‘When they started in the UK, a lot of pharmacists did the prescribing course but there weren’t any positions for them to move into and utilise those skills,’ he said. To date, only 11% of UK pharmacists are registered with the General Pharmaceutical Council are independent prescribers.6 It’s a similar story in New Zealand, where latest figures show there are just 14 registered pharmacist prescribers.7

‘In Australia we could easily get pharmacists doing top-up courses and being qualified, endorsed prescribers – that’s really the easy part,’ Dr Kyle said.

‘The hard part is what are we going to do with them? How are we going to make pharmacist prescribing work within the healthcare system?’

Path to prescribing

It’s for this reason that advocates have said that discussions around prescribing powers should be squarely focused on what’s best for the patient and optimising access to appropriate healthcare professionals.

‘It’s not about stealing turf from other practitioners; it’s about practicing to the full scope of your training and providing better access for patients,’ Dr Kyle said.

‘If we’re looking at what’s truly best for the patient, then it really doesn’t matter who writes that prescription, provided they are appropriately qualified and trained.’

Pharmacists will need to secure the support of a range of stakeholders – including other health professionals, the Board and governments – before they can receive and fully utilise prescribing powers.

There will be details to nut out – pharmacists’ scope of practice, checks and balances, funding and remuneration models, state and federal legislation, training and qualification regimes.

It’s a process that won’t happen overnight, Dr Jackson said, but it can happen. ‘We will certainly be working with the jurisdictions to show why pharmacists should be included in any sort of collaborative prescribing arrangements,’ he said.

‘In my mind, there’s no reason pharmacists shouldn’t be able to prescribe by 2020.’

Training upPharmacists are generally well-placed to prescribe for chronic condition management, but are likely to need some additional training around diagnostics, said QUT Professor of Pharmacy and Head of Discipline Dr Greg Kyle. ‘Our big niche is in chronic therapy management and chronic condition management,’ he said. ‘And if you look at all of the national health priority areas they’re all around chronic conditions – that’s where pharmacists could contribute the most, the fastest.’ The exact training and accreditation regime required for pharmacist prescribers will depend on what’s ultimately outlined in legislation, and endorsed by health ministers and the Board. Pharmacists could, however, expect something similar to Nurse Practitioner courses which require each individual to identify their scope of practice or specialisation, Dr Kyle predicted. ‘Pharmacists who are doing medication reviews are probably more in a generalist model, whereas a senior hospital pharmacist in oncology has gone through that specialisation process,’ Dr Kyle said. ‘That defines the pharmacist’s scope of practice and then we can add on the prescribing toolkit.’ Dr Kyle also anticipated there would be a need for training in diagnostics and monitoring. ‘We’ll need to up-skill in interpreting lab results, imaging and various tests and then making the prescribing decisions,’ he said. A shift in mindset may also be required. ‘A lot of pharmacists live in a world of black and white, right or wrong. The PBS, for example, is paid or it’s rejected,’ Dr Kyle said. ‘But making prescribing decisions, diagnoses and looking at what’s best for the patient is about embracing the shades of grey.’ And that’s where some of the training and on-the-job experience could come in. ‘If you look at medical prescribers, they don’t have as much training as pharmacists in terms of the pharmacology, dose-form, design and so forth, but they build that into their training and residencies,’ Dr Kyle said. |

Prof Lisa Nissen will be presenting a CPD session on pharmacist prescribing at PSA18.

References

- Hoti K, Hughes J, and Sunderland B. An expanded prescribing role for pharmacists – an Australian perspective. Australasian Medical Journal 2011;4(4):236-242.

- Latter S, Blenkinsopp A, Smith A, et al. Evaluation of nurse and pharmacist independent prescribing. Department of Health Policy Research Programme Project 016 0108. University of Southampton; Keele University, 2010.

- Finley P, Rens H, Pont J, Gess S, et al. Impact of a collaborative pharmacy practice model on the treatment of depression in primary care. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2002;59(16):1518–1526.

- Dole E, Murawski M, Adolphe A, et al. Provision of pain management by a pharmacist with prescribing authority. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2007;64(1):85–89.

- Weeks G, George J, Maclure K, et al. Non-medical prescribing versus medical prescribing for acute and chronic disease management in primary and secondary care. 2016. At: http://cochranelibrary-wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011227.pub2/abstract

- Robinson, J. The trials and triumphs of pharmacist i ndependent prescribers. 2018. At: pharmaceuticaljournal.com/news-and-analysis/features/the-trials-andtriumphs-of-pharmacist-independent-prescribers/20204489.article

- Pharmacy Council. Workforce Demographic. 2017. At: pharmacycouncil.org.nz/Portals/12/2017%20Workforce%20Demographic%20Report.pdf

- Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. Increasing the use of collaborative practice agreements between prescribers and pharmacists. 2017. At: cdc.gov/dhdsp/pubs/docs/CPA-Translation-Guide.pdf

- American Academy of Family Physicians. Scope of practice – pharmacists. 2017. At: aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/advocacy/workforce/scope/BKG-Scope-Pharmacists-113017.pdf

- Department of Health. Prescribing by non-medical healthcare professionals. 2018. At: health-ni.gov.uk/articles/pharmaceutical-non-medical-prescribing

- General Pharmaceutical Council. Pharmacist independent prescriber. 2018. At: pharmacyregulation.org/education/pharmacist-independent-prescriber

- Canadian Pharmacists Association. Pharmacists’ expanded scope of practice. 2016. At: pharmacists.ca/pharmacy-in-canada/scope-of-practice-canada/

- Pharmacy Council. Pharmacist Prescriber Scope of Practice. 2017. At: pharmacycouncil.org.nz/Portals/12/Documents/prescribers/Pharmacist%20Prescriber%20Scope%20of%20Practice%20Logo%20update%20Jan2018.pdf?ver=2018-01-17-094226-357

‘We’re increasingly seeing incidents where alert fatigue has been identified as a contributing factor. It’s not that there wasn’t an alert in place, but that it was lost among the other alerts the clinician saw,’ Prof Baysari says.

‘We’re increasingly seeing incidents where alert fatigue has been identified as a contributing factor. It’s not that there wasn’t an alert in place, but that it was lost among the other alerts the clinician saw,’ Prof Baysari says.

Beyond the arrhythmia, AF often signals broader pathological processes that impair cardiac function and reduce quality of life and life expectancy.5 Many of these conditions are closely linked to social determinants of health, disproportionately affecting populations with socioeconomic disadvantage. Effective AF management requires addressing both the arrhythmia and its underlying contributors.4

Beyond the arrhythmia, AF often signals broader pathological processes that impair cardiac function and reduce quality of life and life expectancy.5 Many of these conditions are closely linked to social determinants of health, disproportionately affecting populations with socioeconomic disadvantage. Effective AF management requires addressing both the arrhythmia and its underlying contributors.4  C – Comorbidity and risk factor management

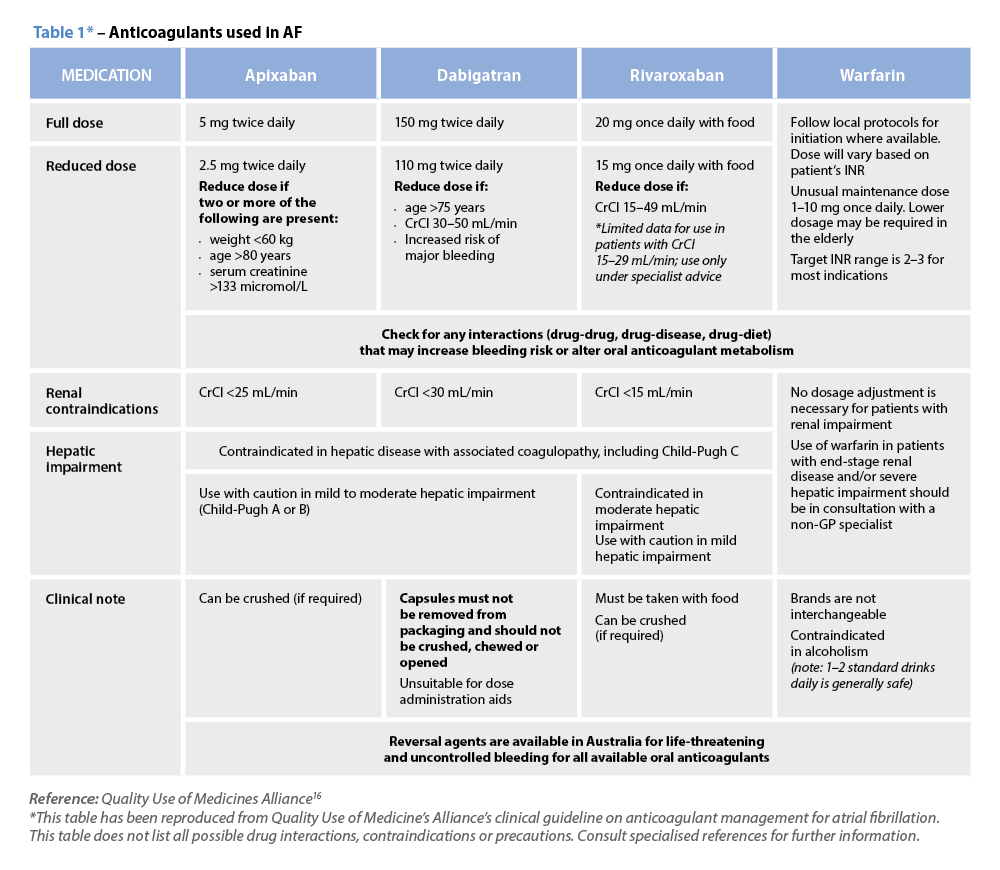

C – Comorbidity and risk factor management Warfarin

Warfarin