In a world of information overload, how can pharmacists prevent patients from falling into a medicine-induced downward spiral?

Every day Australians swallow millions of pills without much awareness of adverse effects or drug interactions.

Problems with medicines are ‘alarmingly common’, according to PSA. The biggest failing in patient safety comes ‘from ineffective communication, rather than a lack of clinical knowledge or skill’, with 250,000 hospital admissions each year for medicine-related problems.1

Yet many people assume that medicines are safe, unless told otherwise. Similarly, many pharmacists and health professionals assume consumers are confident to use medicines safely, unless they disclose pertinent information or ask questions. This clash of assumptions can lead to crucial information gaps that place patients’ health at risk.

Flying blind

Communication gaps and delays are found right across the healthcare system. Often the pharmacist must turn detective to ascertain what consumers know about their medicines – the potential harms and benefits – or if they are taking them correctly, sharing with family and friends, or stockpiling.

Professor Richard Osborne, Director of the Centre for Global Health and Equity at Swinburne University of Technology, says the teach-back communication method is widely used in Australia and internationally by healthcare providers.

Teach-back involves asking the patient to repeat in their own words what a healthcare provider has told them. This ‘checks and balances’ approach puts the onus on the provider to ensure consumers understand their medicines and how to take them safely, Prof Osborne says.

‘If a person can’t recount back accurately, then the healthcare provider can explain it in a different way, maybe using smaller chunks of information.’

And as Deborah Hawthorne MPS, a consultant and general practice pharmacist based in Wangaratta, Victoria, has learned when asking about drug-specific adverse effects during any sort of medicine review, it is useful to build a rapport with a patient by explaining why questions are asked and how some drugs cause certain symptoms to exhibit in the body.

‘If needed, I’ll also ask specific disease-state monitoring questions. For example: “How often do you measure your blood sugar levels at home? Would you mind showing me your book?”

‘If specific issues are identified, I like to raise these with the patient at the interview, as I believe it helps to empower patients to have greater interest in and control over their own health. It also helps to enforce that we are making a plan together, with pharmacist-doctor-patient involvement.’

Professor in Medicines Use Optimisation at the University of Sydney Parisa Aslani MPS, says consumers often accept that prescription drugs may have adverse effects but think that non-prescription and complementary medicines are safe ‘simply because they can buy them off a shelf’.

‘All medications have a risk of harm, even paracetamol,’ she says. ‘Health professionals are fully aware of the harms but consumers aren’t always.’

Every day 9 million Australians take a prescribed medicine, 2 million take non-prescription medicine, and 7 million take a complementary medicine, according to a YouGov Galaxy poll conducted for NPS MedicineWise.2

Health and wellbeing data collected in 2017 by market researcher Roy Morgan found that almost 90% of Australians had taken a medicine in the previous 12 months, with general medicines such as aspirin, paracetamol and ibuprofen the most common, followed by allergy drugs and antihistamines, cold and flu medications, vitamins, supplements and digestive system medicines.3

Prof Aslani advises School of Pharmacy students to obtain a complete picture from consumers of all their medicines. This fact-finding includes consumer awareness of adverse effects, drug interactions, drug and food interactions, allergies, and the complexities of polypharmacy, and requires the pharmacist to have the people skills of emotional intelligence, communication, teamwork and negotiation.

Words matter

Time is also one of the rewards of being a consultant pharmacist, according to Deborah Hawthorne.

‘For an hour or more, we can sit with a patient and get a good feel for their health literacy and general understanding of their medicines – something not always evident in quicker interactions. Another advantage is the ability, generally when meeting a patient for the first time, to ask the most basic of questions. For example: “How many paracetamol tablets do you take on a normal day?”

‘To fully investigate patients’ medicines and disease-state understanding, my consultancy-work interviews, both in the GP clinic and in a patient’s home, follow a rough plan. I also like the conversation to be patient-led where possible, as I find a natural flow will unearth more issues than a one-sided question/answer-type interview.

‘It also allows the patient to say what they want from their medicines. For example: “I wish I didn’t have to take so many (deprescribing hint)”.‘

A patient’s perspectiveDuring a Home Medicines Review, Deborah Hawthorne discovered a patient had seen a television advertisement for [paracetamol] Panadol Rapid and had bought it hoping for relief from chronic back pain. She went through his dose administration aid and his other medicines. ‘It took quite a while to go through everything, e.g. magnesium, [paracetamol] Panadol Rapid, fexofenadine, vitamin D, [docusate] Coloxyl, [dulaglutide] Trulicity (weekly) injections, [glyceryl trinitrate] Nitrolingual Pumpspray, etc,’ the patient told AP. ‘Debbie explained the chemical compound between the [paracetamol SR] Panadol Osteo, which I take 6 a day in my Webster pack (morning, 2 pm and before bedtime), and that by taking the [paracetamol IR] Panadol Rapid it could create a problem in my liver in the near future.’ The patient immediately stopped the [paracetamol IR] Panadol Rapid, and at a later consultation with both his GP and Ms Hawthorne, his nightly temazepam was ceased and [oxycodone/naloxone CR] Targin was reduced. ‘I was advised I could become tolerant to both medications with very little benefit if taken over a long period of time,’ the patient said. ‘Deborah’s expertise and help have been tremendous.’ |

Body language is important

At the University of Sydney, Prof Aslani teaches the next generation of pharmacists how to use their people skills to assess and understand patients’ needs.

She tells students that ‘80% of what people are telling you is through non-verbal language’ – eye movement, body language, and facial expressions that convey to the pharmacist if the consumer is anxious.

‘You can then map that non-verbal communication to what the person is telling you and what they’re asking for,’ she says. ‘If someone is anxious in the pharmacy with their first presentation for prescriptions for diabetes, for example, they will need to ask lots of questions but they may not know where to start.’

ILWOO PARK MPSManager, Oatlands Pharmacy, Oatlands, Tasmania Tasmania’s Early Career Pharmacist of 2020 finds the teach-back method easier, as a non-native English speaker, to check whether both her pronunciation and her explanation have been understood by her patients. When switching antidepressants, Ms Park says she explains the washout periods, how to be safe, and how many pill-free days are necessary. Then she asks: ‘Did I explain that OK?’ After a usually affirmative answer, she continues: ‘So you took the [fluoxetine] Lovan this morning. Could you tell me when you need to take this new tablet? I would like to check that I didn’t confuse you and keep you safe.’ The answer is often a smile and the response: ‘I won’t take anything for 7 days and will start this new tablet next Wednesday morning. You did well!’ On preventive inhalers for those with asthma who already use a reliever, Ms Park explains the differences between the new preventer and the current blue puffer, emphasises regular use, and demonstrates how to use it. ‘Then I ask: “Did I show you clearly? You can’t just say yes, because it’s your turn next when you show me!” Then I show them one more time.’ Ms Park then talks the patient through the correct technique. ‘So, first? Yap… yap… yes… and hold breath… and yes, what about the lid? The last step? Where’s the water?’ Some people, Ms Park says, recite each step out loud. Then she explains that the new preventer is to be used each day ‘whether you feel good or bad’, and the blue one is for breathing difficulties. She stresses the devices do not replace each other, but with more use, the preventer will mean less use of the blue puffer. ‘You will feel the difference, but not straight away. If not, please come back.’ |

Bridging the gap

Prof Osborne led the team that developed the Health Literacy Questionnaire used for the Australian Bureau of Statistics National Health Survey: Health Literacy, 2018.

The survey found that a third of Australians believe it is always easy to discuss health concerns and engage with their healthcare providers, 56% say it is usually easy, and 12% find it difficult.

The World Health Organization has called for health literacy – the ability of individuals to access, understand, remember and use information to improve and maintain good health – to be seen as a community benefit rather than an individual deficit.

Governments, health systems and healthcare providers, therefore, have a collective responsibility to present clear, accurate, appropriate and accessible information for diverse groups.

‘Health literacy has blossomed into being a health promotion mechanism by which we can understand people’s strengths as well as their challenges,’ Prof Osborne says.

Pharmacists, who are perhaps the most accessible healthcare providers, have the ‘extraordinary opportunity’ to provide vital information to consumers, regardless of their level of health literacy.

‘People need “what to do” information, “how to do” information, and “when to do” information,’ he says. This can compensate for consumers’ low health literacy and lack of skills, as well as for other healthcare providers’ lack of time.

‘Pharmacists are incredibly important mediators between the medical profession and the family, and the powerful life-saving drugs some people really need to take,’ Prof Osborne says.

FIGURE 1 – Better-targeted questions

Instead of saying . . . |

Perhaps try . . . |

| Do you have any questions? | What questions do you have? (An example to prompt might be: Have you ever been worried about side effects or drug interactions?) |

| Take four times each day on an empty stomach | Taking a capsule four times a day on an empty stomach can be hard to organise. Can you explain for me how you will fit this into your daily meal routine for the next 5 days? |

| Do you take any other medicines? | This tablet can cause problems with some medicines, particularly antidepressants and diabetes medicines. What other medicines do you use? |

| Have you used this medicine before? | How effective has this medicine been for you in the past? OR If you had to give this medicine a score out of 10, what would it be? |

| Take this tablet every morning | When would you usually take your medicine? |

Assumption . . . |

Safer practice: Assume little to no knowledge with questions like . . . |

| Assuming patients know their medicines well | Why do you use that medicine? How do you take it? What time of day? Is it every day or just when you need it? How do you remember to take it regularly? |

| Assuming adverse effects are known to the patient | Have you ever experienced muscle soreness? What was the pain like (for muscle issues with statins)? |

| Directing what should happen when specific issues are identified | You’ve taken that PPI for X amount of time, but haven’t had any reflux symptoms for Y amount of time. As long-term use of PPIs can lead potentially to vitamin B12 deficiency and an increased risk of fractures from falls, would you be open to reducing the PPI dose, making it ‘when required’ or ceasing it altogether with an antacid or H2 antagonist on hand if needed? |

| What other medicines and natural supplements do you take (of which the GP may be unaware)? | Have I forgotten to ask about other medicines you might use? What others – vitamin supplements, puffers, creams, etc – do you use? What do you use for pain, say, for a headache or sore muscles? How often do you use these products? Have you bought anything else from the pharmacy lately? |

References

- Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. 2019. Connecting the dots: digitally empowered pharmacists. At: psa.org.au/advocacy/working-for-our-profession/connecting-the-dots-digitally-empowered-pharmacists/

- NPS Medicinewise. With millions taking multiple medicines, Australians are reminded to Be MedicineWise. 2018. At: nps.org.au/media/with-millions-taking-multiple-medicines-australians-are-reminded-to-be-medicine-wise

- Roy Morgan. Almost 9-in-10 Australians take medication of some kind. 2018. At: roymorgan.com/findings/7598-health-medications-taken-december-2017-201805201234

Build your skills with PSA Short Courses at www.psa.org.au/psashortcourses

‘We’re increasingly seeing incidents where alert fatigue has been identified as a contributing factor. It’s not that there wasn’t an alert in place, but that it was lost among the other alerts the clinician saw,’ Prof Baysari says.

‘We’re increasingly seeing incidents where alert fatigue has been identified as a contributing factor. It’s not that there wasn’t an alert in place, but that it was lost among the other alerts the clinician saw,’ Prof Baysari says.

Beyond the arrhythmia, AF often signals broader pathological processes that impair cardiac function and reduce quality of life and life expectancy.5 Many of these conditions are closely linked to social determinants of health, disproportionately affecting populations with socioeconomic disadvantage. Effective AF management requires addressing both the arrhythmia and its underlying contributors.4

Beyond the arrhythmia, AF often signals broader pathological processes that impair cardiac function and reduce quality of life and life expectancy.5 Many of these conditions are closely linked to social determinants of health, disproportionately affecting populations with socioeconomic disadvantage. Effective AF management requires addressing both the arrhythmia and its underlying contributors.4  C – Comorbidity and risk factor management

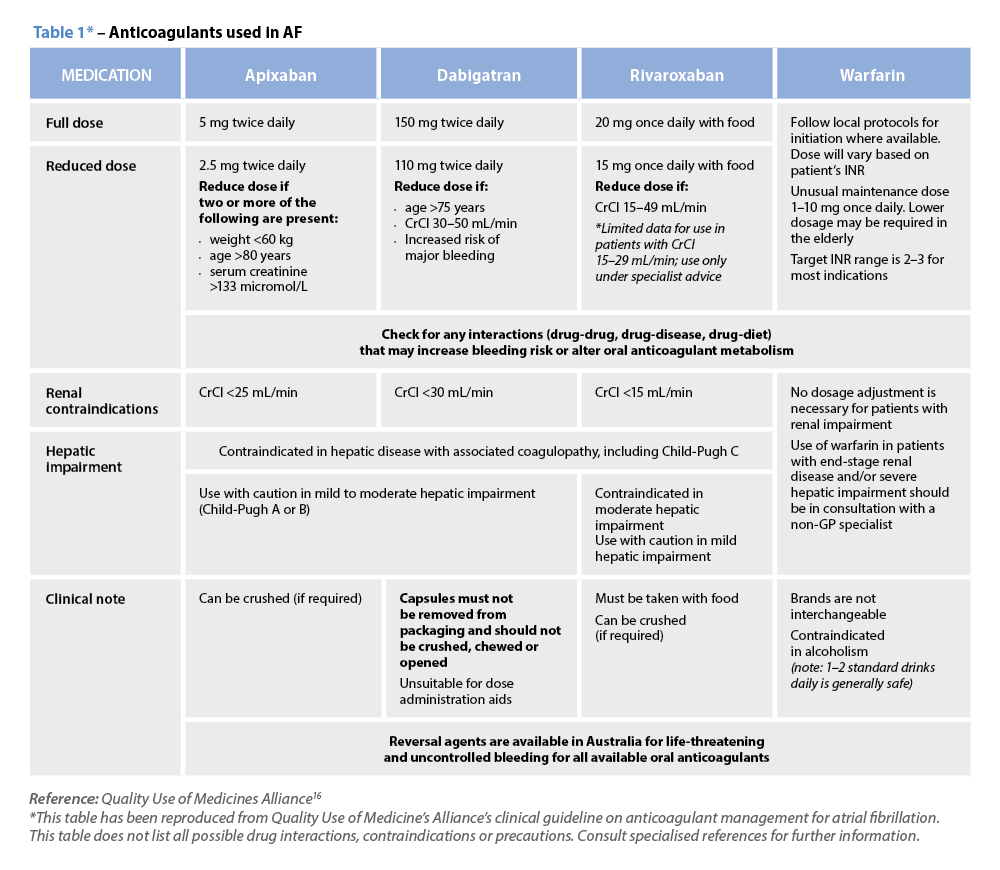

C – Comorbidity and risk factor management Warfarin

Warfarin