Concerns over the overuse of antipsychotics in Residential Aged Care Facilities have reached a high tide – but so have efforts to address the issue by giving pharmacists a larger role to play.

‘The hallmark of a civilised society is how it treats its most vulnerable people, and our elderly are often amongst our most physically, emotionally and financially vulnerable.’

That’s the tone that Commissioner Richard Tracey set at the opening of the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety in January.

Managing and minimising the use of physical and chemical restraint is a top priority of the Royal Commission and already the Federal Minister for Aged Care has announced draft changes to regulations governing their use.

Concern around antipsychotic drug use in residential aged care facilities (RACFs) is not new. In fact, red flags were raised at least two decades ago, says Dr Juanita Westbury, pharmacist and senior lecturer in dementia studies at the University of Tasmania’s Wicking Dementia Research and Education Centre. ‘I’ve been researching it for over a decade and you get these periods of intense focus on the area and then you don’t hear very much for a period of time. So I hope that this time there will be some sustainable change,’ says Dr Westbury.

The Third Australian Atlas of Healthcare Variation,1 released in December, showed that antipsychotic prescriptions among older Australians remain a significant concern.

‘For people aged 65 years and over, prescription rates of antipsychotic medicines decreased during the four years [between 2013–2014]; however, the volume of antipsychotic medicines supplied on any given day in the Australian community remained stable, indicating that there has been little change in the overall amount of use during the four years,’ the report stated.

‘The current use of antipsychotic medicines outside current guideline recommendations as a form of restrictive practice to manage behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) in aged care homes is a matter of grave concern.’

The Atlas found that 25,788 prescriptions are dispensed per 100,000 people aged 65 years and over – down 6% from 27,396 in 2013–14.

However, the volume of antipsychotic medicines remained stable over the four-year period, with 11.54 defined daily doses of antipsychotic medicines per 1,000 people dispensed on any given day.

The University of Sydney’s Head of School and Dean of Pharmacy, Professor Andrew McLachlan FPS, says the findings are disappointing.

‘Despite a number of initiatives to try and increase awareness and reduce the use of antipsychotics and sedatives in aged care facilities, there hasn’t been much change in the use of antipsychotic medicines,’ says Professor McLachlan, who is also Program Director of the National Health and Medical Research Council’s (NHMRC) Centre for Research Excellence in Medicines and Ageing.

‘We haven’t seen growth – that’s an important conclusion. But we certainly haven’t seen a substantial reduction. Perhaps it means that it’ll take longer than just four years to start to see substantial reductions in the use of those medicines, or that we need to redouble our efforts with more effective interventions.’

Another recent Australian literature review focusing specifically on residents of RACFs shows studies have found that between 13% and 42% of RACF residents are prescribed an antipsychotic.2

Consequences

Research shows that antipsychotics offer only modest benefit for treating BPSD and are associated with significant harms, says Dr Westbury.

‘Because of the adverse effects associated with these drugs, you should only be using them when there is a risk of harm and when non-drug strategies have been tried,’ she says.

She points to research summarised in the 2016 Royal Australian New Zealand College of Psychiatry’s (RANZCP) Professional Practice Guideline 10.3

‘There have been numerous placebo-controlled trials and several meta-analyses examining the efficacy of antipsychotic medications to treat BPSD. These studies show a small effect size of 0.13 to 0.20.4 Notably, this effect size is smaller than some nonpharmacological approaches to treatment of BPSD,’ the guidelines state.

‘In general, antipsychotic medications are associated with increased risks of central nervous system adverse events, sedation, exacerbation of existing cognitive impairment and confusion, fractures, falls, urinary tract infections, deep venous thromboses, peripheral oedemas, gait disturbances, akathisia and Q-T prolongation.’

Additionally, the guidelines state that risperidone may be associated with a three-fold risk of cerebrovascular events,5 and ‘there have been a number of observed associations between mortality and the use of both conventional and atypical antipsychotics’.6,7 Antipsychotic medicines are also associated with confusion, falls, pneumonia, hip fracture and stroke.8,9,10

Reducing use, improving care

There is no easy fix when it comes to reducing the use of antipsychotics and improving care in RACFs, admits Professor McLachlan. ‘The challenge of the inappropriate use of a medicine isn’t just about a doctor writing a prescription and a pharmacist dispensing it,’ he says. ‘It relates to the nature of the patient cohort that’s coming into aged care facilities, the facilities themselves and what infrastructure they have, but most importantly what staffing profile they have.’

For pharmacists, however, there are a number of programs and tools that have been developed to help improve the situation.

The 2014–2016 pharmacist-led ‘RedUSe’ (Reducing Use of Sedatives) project reduced antipsychotic use in 150 RACFs in six states and the ACT by 13% and benzodiazepine use by 21%, without increasing pro re nata (prn) or sedating antidepressant psychotropic drug use.11

Lead author of the resultant Medical Journal of Australia paper, Dr Westbury, says that although funding for the project has ceased, pharmacists can continue to implement its main strategies in RACFs.

‘Basically it uses quality use of medicines (QUM) improvement strategies and provides education,’ she says.

‘It starts off with a psychotropic medication audit and then that’s presented to the staff in a very interactive training session – we really try to challenge the beliefs of the nursing staff that these medications are effective, talk about adverse effects and the evidence of only modest effectiveness.’

The project takes six months and includes an interdisciplinary case review of all residents taking antipsychotics and benzodiazepines by a pharmacist, nurse and GP at baseline and three months, then a final audit at six months. ‘Pharmacists can really make a difference – we found that 40% of the residents taking antipsychotics at the beginning of the project either had a complete cessation, or a reduction in their psychotropic medication, by 6 months,’ says Dr Westbury.

The Halting Antipsychotic use in Long Term care (HALT) Project is another interdisciplinary approach shown to help reduce antipsychotic use in RACFs.

The Sydney-based study in 23 RACFs involved the establishment of an antipsychotic deprescribing protocol. General practitioners, pharmacists and residential care nurses were then educated about non-pharmacological, person-centred BPSD prevention and management. Trained nurse ‘champions’ then passed on their knowledge to other nurses.

Results show that 95% of consenting RACF residents taking a regular antipsychotic at the start of the study had ceased antipsychotic use at the 12-month mark.12 Importantly, there was no change in BPSD or adverse outcomes.

Reports

Report generation tools available through pharmacy software, such as Webstercare Medication Management Software (MMS), can be used to improve QUM in RACFs, says Webstercare founder and managing director Gerard Stevens FPS.

The Webstercare Medication Advisory Committee (MAC) report, for instance, can be generated to help raise awareness and drive change, Mr Stevens says.

‘It actually shows the percentage of people who are on particular antipsychotic drugs at a facility. And showing this graph has a real impact when people look at it,’ he says. ‘In my experience the nurses, particularly the directors of nursing, are very sensitive to this report. They don’t want to be singled out for inappropriate use of antipsychotics.’

Webstercare’s anticholinergic report – the Drug Burden Index report – is another useful tool.

‘Just by running a report on all the people in a particular aged care facility you can identify those people who are potentially at risk, identify those people to be reviewed by their doctor, or reviewed by the consultant pharmacist who is doing medication reviews,’ says Mr Stevens.

Webstercare has also collaborated with NPS MedicineWise to develop a reporting function within MMS that creates in-depth reports of the use of antipsychotic medicines in RACFs. This allows comparison of medicine use against published results and flags residents for Residential Medication Management Reviews (RMMRs).

‘I would say to pharmacists, use the tools that are at your fingertips. The impact is really worthwhile,’ he says.

Embedding pharmacists in RACF

While a number of programs and tools have been shown to help reduce the use of antipsychotics in RACFs, many suffer from lack of ongoing funding. Dr Westbury, for example, says that during the RedUSe project, ‘we had pharmacists saying that they weren’t funded adequately to visit RACFs and the current reimbursement for QUM is very low’.

Her preferred solution echoes that identified by PSA in its Pharmacists in 2023 report13: embedding pharmacists within healthcare teams to improve decision making for the safe and appropriate use of medicines.

‘If you’ve got a pharmacist in aged care who is trusted by the staff and doctors and knows the residents, surely that would enhance their results, rather than some random person coming in and doing recommendations,’ she says.

‘Part of good quality care is inter-professional working, so having a pharmacist in an aged care facility would really assist that as well.’

Professor McLachlan would also like to see pharmacists embedded in RACFs providing antipsychotic stewardship.

‘They would be mimicking that model of care that we know to be very effective in the antimicrobial and opioid spaces, and extending into an intervention for antipsychotic medicines and sedatives in aged care,’ he says. ‘Perhaps pharmacist-led, but involving other healthcare professionals – including nursing, occupational therapy, physicians and general practitioners. That’s the type of strategy which would see sustained changes.’

ON THE GROUNDLast year Richard Thorpe became the first pharmacist in Australia appointed to a full-time position in a RACF, in the ACT. AP: What does your role involve?RT: I attend the morning handover and prioritise my workflow for the day based on the needs of the residents. I’ll regularly attend morning medication rounds, which has been particularly effective when carers have residents who have been refusing doses consistently. Observing these interactions allows me to both ‘coach’ staff and provide feedback to the GP or enduring power of attorney (EPOA) if needed. My work activities are divided into about eight different areas. GP and pharmacy liaison have taken priority early on, however in the months ahead I expect to provide input into policy and procedure. Staff training will also be prioritised. I also conduct formal RMMRs, attend case conferences, and co-ordinate and run training for medical assistants. AP: What feedback have you received?RT: Residents, EPOAs and family members who have attended case conferences have provided feedback on my ability to encourage residents to make informed decisions around medicine use. The GPs have said that having a pharmacist present allows more informed discussions, particularly where deprescribing is concerned. The Registered Nurses (RNs) and care staff have indicated they appreciate advice regarding the administration of medications – whether medications can be crushed safely, and if not, what alternatives are available; clarification of regimens when residents return from hospital; timely charting and supply of medications for new admissions. Residents are also getting used to seeing me each day. Some pull me aside seeking advice or reassurance, which allows me to become their advocate to the GP, RN or care staff if necessary. AP: What do you hope to achieve in this role?RT: With my knowledge base and experience, I feel I’ll be able to provide valuable input to encourage residents and their EPOAs to make high-quality decisions regarding medication management. I will have an impact on policy and procedure and will be chairing the Medication Advisory Committee (MAC) meetings in 2019. I’ll also be part of the Antibiotic Stewardship Committee and provide opinion to the Clinical Governance Committee. While these ‘management’ type roles will help mould the DNA of the organisation, I also want to maintain my presence on the facility ‘shop floor’ to provide support to staff on a daily basis. |

On the ground

When Richard Thorpe joined the team at Goodwin Aged Care Services in Canberra, he became the first pharmacist appointed to a full-time position in residential aged care in Australia (see breakout). But he’s keen to see other pharmacists share that title before too long.

‘Easy access to a pharmacist to provide advice on the safe use of antipsychotics in a timely fashion is key in helping to prevent the overuse of these medicines,’ says Mr Thorpe. ‘A pharmacist working in a RACF is well placed to provide education for facility staff, prescribers and residents’ families, which may cover appropriate and inappropriate uses of antipsychotics in managing concerning behaviour such as wandering, inappropriate voiding, verbal aggression or screaming.’

And he stresses that an on-site pharmacist can offer a unique service.

‘The role is different from that of an RMMR or QUM pharmacist in that I can gauge the needs of the facility on a day-to-day basis,’ he says. ‘If there is an acute issue where I am not rostered I still have access to all the relevant information. This allows me to give advice in real time, which benefits the resident.’

In the meantime, it’s important to acknowledge the hard work that many pharmacists are already doing in this space, says Webstercare’s Gerard Stevens.

‘Pharmacists are providing an amazing service in aged care – they go to the MAC meetings, they’ll do after-hours calls, they’ll write reports and intervene in drug-related incidents like drug interactions,’ he says. ‘Pharmacists need to be patting themselves on the back a bit more.’

The PSA will be making a submission to the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety and invites interested pharmacists to share their thoughts by Monday 13 May to help inform its feedback. Email: agedcareRC@psa.org.au |

References

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. The Third Australian Atlas of Healthcare Variation. 2018. At: safetyandquality.gov.au/atlas/the-third-australian- atlas-of-healthcare-variation-2018/

- Westaway K, Sluggett, J, Alderman C et al. The extent of antipsychotic use in Australian residential aged care facilities and interventions shown to be effective in reducing antipsychotic use: A literature review. August 2018. Dementia. At: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30153745

- Professional Practice Guideline 10: Antipsychotic medications as a treatment of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. 2016. At: www.ranzcp.org/_les/resources/college_statements/practice_ guidelines/pg10-pdf.aspx

- Schneider L, Dagerman K, Insel P. Efficacy and adverse effects of atypical antipsychotics for dementia: meta-analysis of randomised, placebo-controlled trials. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2006;14:191–210. At: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16505124

- Committee on Safety of Medicines. Atypical antipsychotic drugs and stroke. 2004. At: webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20141205150130/ http://www.mhra.gov.uk/home/groups/pl-p/documents/websiteresources/con019488.pdf

- Kales H, Kim H, Zivin K et al. Risk of mortality among individual antipsychotics in patients with dementia. American Journal of Psychiatry 2012;169: 71–79. At: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22193526

- Huybrechts K, Gerhard T, Crystal S et al. Differential risk of death in older residents in nursing homes prescribed specific antipsychotic drugs: population cohort study. British Medical Journal 2012;344:e977. At: https://www.bmj.com/content/344/bmj.e977

- Pratt N, Roughead E, Ramsay E at al. Risk of hospitalization for stroke associated with antipsychotic use in the elderly: a self-controlled case series. Drugs Aging 2010;27:885–93. At: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20964462

- Pratt N, Roughead E, Ramsay E et al. Risk of hospitalization for hip fracture and pneumonia associated with antipsychotic prescribing in the elderly: a self-controlled case-series analysis in an Australian health care claims database. Drug Safety 2011;34:567–75. At: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21663332

- Tampi R, Tampi D, Balachandran S et al. Antipsychotic use in dementia: a systematic review of benefits and risks from meta-analyses. Ther Adv Chronic Dis 2016;7:229–45. At: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27583123

- Westbury J, Gee P, Ling T et al. RedUSe: reducing antipsychotic and benzodiazepine prescribing in residential aged care facilities. Med J Aust 2018;208(9):398–403. At: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29747564

- Jessop T, Harrison F, Cations M et al. Halting Antipsychotic Use in Long-Term care (HALT): a single-arm longitudinal study aiming to reduce inappropriate antipsychotic use in long-term care residents with behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2017 Aug;29(8):1391–1403. At: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28266282

- Pharmacists in 2023: For patients, for our profession, for Australia’s health system. 2019. At: www.psa.org.au/advocacy/working-for-our-profession/pharmacists-in-2023

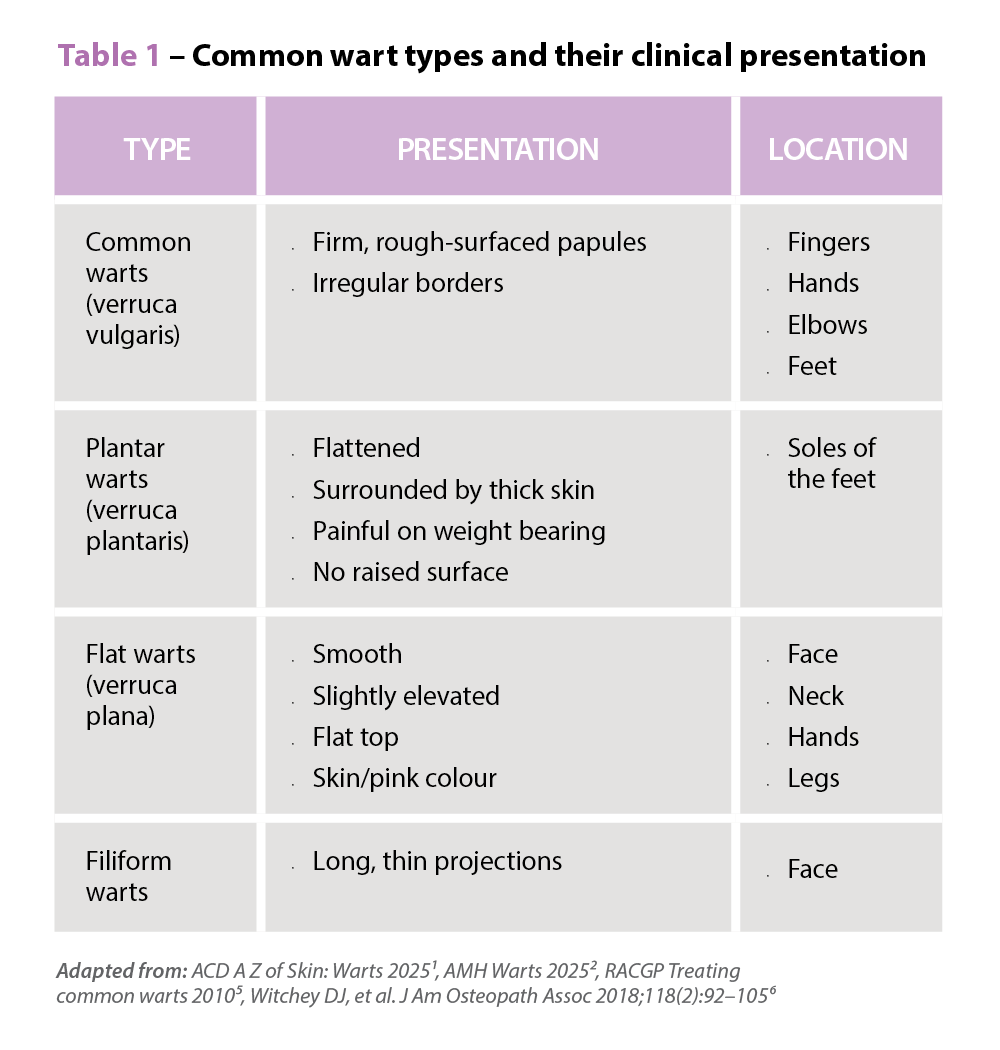

Symptoms

Symptoms