A breathless history of the humble puffer

In 1955 Susie Maison was a 13-year-old asthmatic. She was also the daughter of George Maison, president of Riker Laboratories in Manhattan. Annoyed by her glass squeeze-bulb nebuliser, she asked her father: ‘Daddy, why can’t they put my asthma medicine in a spray can like they do hair spray?’1,2

Two months later the laboratory was trialling two asthma treatments using the first-ever metered-dose inhaler (MDI). They hit the market in 1956, and the convenient technology took off.

Today, MDIs are the most popular system for delivering drugs to the lungs, and Australians consume millions of inhalers annually.1-3

From past to present

Archaeological and historical evidence reveals that, like Elizabeth, people have been tackling respiratory symptoms by inhaling substances for millennia.

Ancient Chinese inhaled opium smoke, while Greeks breathed in burning herb and resin fumes. Written records begin with Egypt’s Ebers Papyrus about 1554 BCE. It describes patients inhaling smoke from a burning black henbane plant covered by a jar topped with a hole.1,2

Over the centuries, many different therapeutic agents were used, among them atropine, ephedra and related compounds.

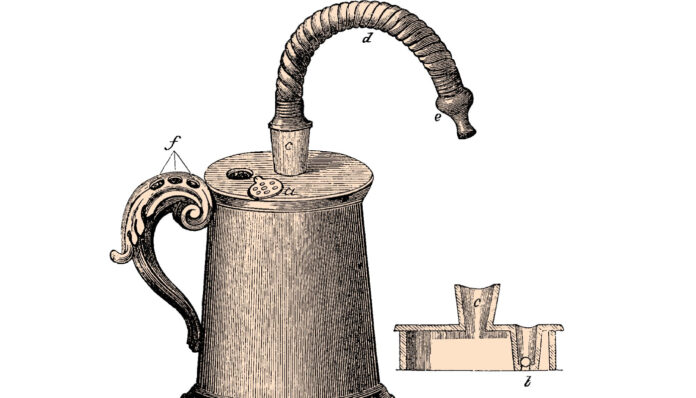

However, the medicine delivery device continued to be custom-made by the patient or attending physician. It wasn’t until the industrial revolution that the first ‘off the shelf’ inhaler was introduced by English physician John Mudge in 1778.1,2

Thanks to new manufacturing technology, Mudge’s concept was a success. It spawned the commercialisation of diverse inhalers – even asthma cigarettes – well into the 20th century.1,2

Types today

Modern pharmacies are stocked with three classes of inhalers for treating asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases. Dry powder inhalers (DPIs) are activated by the patient’s inhalation, and soft mist inhalers (SMIs) produce a fine mist without a propellent. But George Maison-style MDIs require a propellant, either the patient’s breath or a gas. And there’s the catch.4,5

Montreal matters

Prior to 1995, all gas-delivered MDIs used chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) propellants. Unfortunately, in 1974 scientists implicated CFCs in the depletion of the ozone layer. Fortunately, nations acted.

The Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer was ratified in 1987 and entered into force in 1989, the year Australia signed on. With few exceptions, CFCs would be phased out by 1996.3,4,6-9

The agreement led to a surge in pharmaceutical research, as chemists sought to devise CFC-free inhalers and more affordable DPIs and SMIs.

A breakthrough came with the development of CFC-free propellants. Like hydrofluoroalkane (HFA) and hydrofluorocarbon (HFC).

But while they are ‘ozone safe’, both are potent greenhouse gases. Time for another phase-out.2,3,11

So, in 2017 Australia became one of the first 10 countries to ratify the 2016 Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol. Signatories will have until 2036 to reduce their use of HFCs and HFAs by 85%. 6,8,10-13,17,18

Back in the lab

Meanwhile, researchers are devising new propellants. For instance, in 2019 the Chiesi Group – headquartered in Parma, Italy – announced it would launch the first alow greenhouse gas inhaler in 2025.

Chiesi claims the ‘carbon footprint’ will be similar to a DPI.

If so, that’s a breath of fresh air.14-16

References

- Williams K. How Inhalers Have Evolved, One Breath at a Time. Everyday Health 2022.

- Stein SW, Thiel CG. The History of Therapeutic Aerosols: A Chronological Review. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv 2017;30(1):20–41.

- McDonald KJ, Martin GP. Transition to CFC-free metered dose inhalers–into the new millennium. Int J Pharm 2000;201(1):89–107.

- Urrutia-Pereira M, Chong-Neto HJ, Winders TA, et al. Environmental impact of inhaler devices on respiratory care: a narrative review. J bras pneumol 2022;48(06).

- NPSMedicinewise. Inhaler devices for respiratory medicines. 2021.

- UN Environment Programme. Ozone Secretariat. The Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer. 2020.

- Australian Government. Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water. Australia’s implementation of the Montreal Protocol. 2021.

- UN Environment Programme. OzoneAction. About Montreal Protocol.

- American Chemical Society National Historic Chemical Landmarks. Chlorofluorocarbons and Ozone Depletion. 2017.

- Australian Government. Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water. Australia commits to phase down potent greenhouse gases. 2017.

- Montgomery BD, Blakey JD. Respiratory inhalers and the environment. Aust J Gen Pract 2022;51(12).

- Australian Government. Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water. Phasing out and phasing down substances controlled by the Montreal Protocol – Australia’s 2021 progress report. 2022.

- UN Environment Programme. World takes a stand against powerful greenhouse gases with implementation of Kigali Amendment. 2019.

- Chiesi Group. Chiesi outlines €350 million investment and announces first carbon minimal pressurised Metered Dose Inhaler (pMDI) for Asthma and COPD. 2019.

- Rees V. Environmentally friendly pressurised Metered Dose Inhaler to be developed Eur Pharm Rev. 2019.

- Cefic Sector Group. European FluoroCarbons Technical Committee. European pharmaceutical company announces low GWP HFC-152A metered dose inhaler (MDI). 2020.

- Australian Government. Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water. Response to inquiry from Leigh Dayton 20 April 2023.

- UN Environment Programme. OzoneAction. Response to inquiry from Leigh Dayton 20 April 2023.

John Jones MPS, pharmacist immuniser and owner of My Community Pharmacy Shortland in Newcastle, NSW[/caption]

John Jones MPS, pharmacist immuniser and owner of My Community Pharmacy Shortland in Newcastle, NSW[/caption]

Debbie Rigby FPS explaining how to correctly use different inhaler devices[/caption]

Debbie Rigby FPS explaining how to correctly use different inhaler devices[/caption]

Professor Sepehr Shakib[/caption]

Professor Sepehr Shakib[/caption]

Lee McLennan MPS[/caption]

Lee McLennan MPS[/caption]

Dr Natalie Soulsby FPS, Adv Prac Pharm[/caption]

Dr Natalie Soulsby FPS, Adv Prac Pharm[/caption]

Joanne Gross MPS[/caption]

Joanne Gross MPS[/caption]