Paracetamol overdose is common and complex. Here’s how pharmacists can curb the risk of overdose.

Each year, there are 220,000 calls made to four interlinked Poisons Information Centres around the country.

As the largest centre open for the longest hours, the New South Wales branch fielded over 120,000 calls in 2021 alone, said Genevieve Adamo MPS Senior Pharmacist at the NSW Poisons Information Centre, who delivered a session on the subject at PSA22.

‘Paracetamol tops the list every year, by more than double the next closest single agent – ibuprofen,’ she said. ‘That equates to one call for every hour that we are open taking calls,’ she added.

The ranking is reflective of immediate or sustained-release formulations only and does not take combination analgesics or paracetamol containing cold and flu medicines into account.

This further reemphasizes the toxicity of commonly encountered OTC based analagesics being Paracetamol and ibuprofen that can be easily assessable by the public. #PSA22SYD pic.twitter.com/XUpCkiXZ3G

— Raymond Truong (@truryAdelaide) July 31, 2022

The risk assessment process

When a call comes through to the Poisons Information Centre, the team needs to perform a risk assessment. This involves taking a detailed history from the patient including their age, weight, and other medical conditions or medicines that may be applicable.

Next, they need to identify the agent, how much the patient has been exposed to, when they were exposed, the type of exposure, whether it was intentional, if they have any symptoms or if any investigations or treatments have begun. All this information is gathered within the space of 3 minutes.

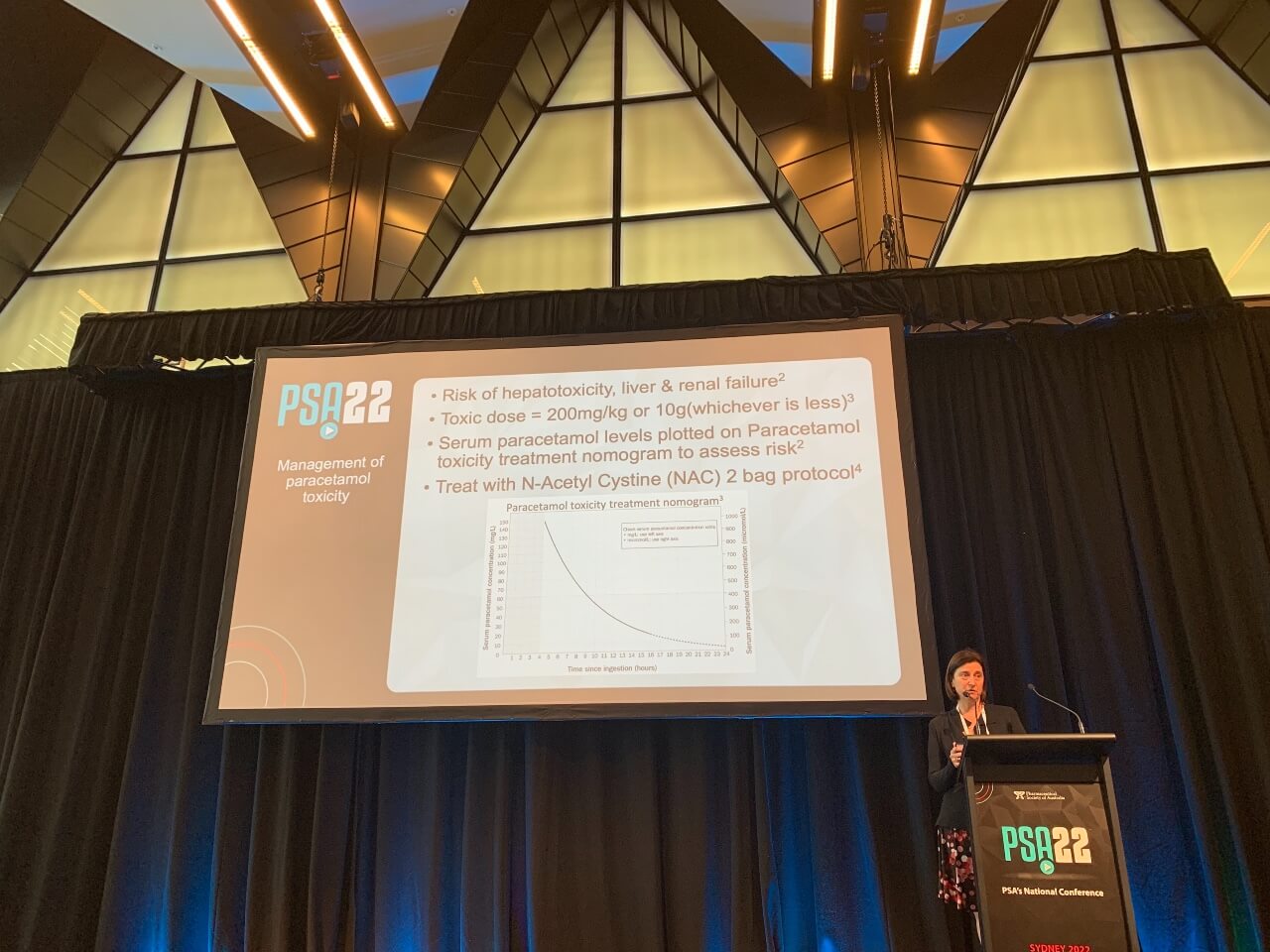

For paracetamol-related calls, the team needs to determine whether a toxic dose has been ingested. While death from paracetamol overdose is rare, it carries a risk of hepatotoxicity and renal failure.

‘In Australia, we use a cut off of 200 mg per kilogram, or 10 g, whichever is less,’ Ms Adamo said.

If that is the case and the patient has been admitted to hospital, a serum paracetamol level needs to be performed. This is plotted on the Rumack-Matthew Nomogram, with paracetamol level on the y-axis and the time since ingestion on the x-axis.

‘If it’s above the line on the nomogram, then we know this patient is at risk of hepatotoxicity so they need to have an antidote,’ she said.

The standard protocol for the antidote is N-acetylcysteine (NAC) at a dosage of 200 mg per kg over 4 hours, followed by a second infusion of 100 mg per kg over 16 hours.

While this seems simple enough, Ms Adamo said, managing paracetamol poison inquiries is anything but.

A complex medicine

Paracetamol is in nearly every house in Australia, and is used in every age group – from 1 month of age through to elderly patients.

The massive amount of paracetamol in the community means it has the potential to be involved in all sorts of exposures, Ms Adamo said.

Accidental therapeutic errors are commonplace, whether both parents dose a small child, the child gets into an unsecured bottle of paracetamol, or a parent accidentally picks up the 5–12 year liquid formulation instead of a 1–5 year bottle.

And despite being a routine counselling point, taking multiple paracetamol-containing medicines without realising they are doubling up remains prevalent.

Poisonings through deliberate self harm are similarly common.

‘[Paracetamol] is readily available, both in community pharmacies and in other retail settings,’ Ms Adamo said. ‘If people are aware it’s toxic, it’s often an agent of choice for [those] looking to self harm.’

All these different types of exposures to paracetamol carry different risks, making overdoses complex to manage.

If ingestion is staggered or the time of ingestion is unknown, this further complicates matters.

‘We can’t use the nomogram, because we don’t have the time since ingestion to plot out,’ she said.

Patients who are started on NAC within 8 hours of exposure have a good chance of avoiding hepatotoxicity. But delayed exposure increases the risk.

‘We need to do more monitoring on these people and they need to have longer treatment courses,’ she said. ‘Some people have allergic reactions to NAC and that throws another spanner in the works.’

When it comes to formulations, modified release paracetamol is the biggest culprit. Because of its erratic absorption and the formation of bezoars, overdose carries a greater risk of hepatotoxicity, even if the patient is started on the antidote at an appropriate time.

‘It [also] comes in packs of 96 tablets, so people don’t just take 10 or 12 tablets, they take 60 or 70 tablets,’ Ms Adamo said. ‘We get these massive exposures [30 g or over], and they require different treatment and monitoring because [there is] an increased risk of hepatotoxicity.’

Education and counselling

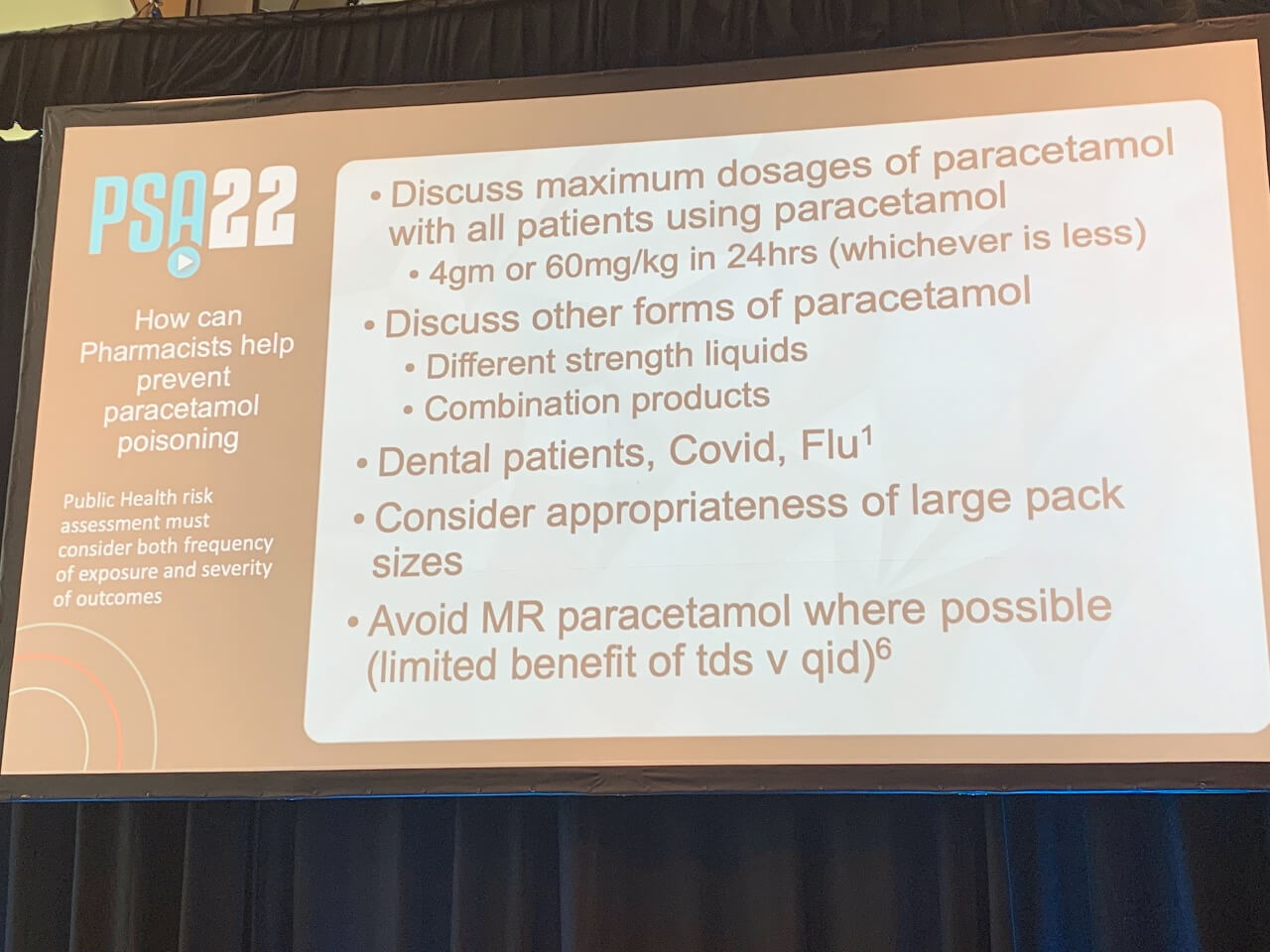

To minimise the number of paracetamol poisonings and the complex after-effects, Ms Adamo said it’s essential to educate patients about maximum dosages and potential risks.

‘The ones who tend to get into real trouble are those taking paracetamol acutely but regularly, [for example] for COVID-19, flu or dental pain,’ she said.

These patients often take increased doses for pain relief, with COVID-19 ‘brain fog’ also contributing to the risk of dosing errors.

‘Talk to these people about recording dosages and making sure they don’t exceed the maximum,’ Ms Adamo advised.

Pharmacists should also emphasise the importance of safe storage and ensuring medicines are put away after they have been used. For example, storing a bottle of paracetamol away rather than leaving it by a child’s bedside if it was used overnight.

Scheduling and supply

Because deliberate self-poisonings are typically impulsive, with people taking whatever agent they have access to, pharmacists should be alert to the appropriateness of supplying large pack sizes of paracetamol.

‘If it’s a family [with] four teenage kids who all have the flu, a pack of 100 is appropriate, because at maximum dosages we’re going to go through it in 3 or 4 days,’ she said.

‘But if you’ve got a 17-year-old girl who’s coming in for her script of fluoxetine and a pack of 100 paracetamol for a headache, I’d question that.’

In this event, Ms Adamo suggests saying: ‘If it’s just for a headache, you’re not going to need that many, they’ll go out of date before you use them all. You’d be better off getting a small pack and coming back for more if you need them.’

Pharmacists should also be aware of why the modified release formulation was upsheduled to a Pharmacist Only Medicine.

‘Every time you pick up a schedule 3 [medicine], think: What is the poisoning risk? What is the safety risk? Why is this schedule 3?’ she said.

‘We know scheduling works to prevent poisoning but only if you know the risks and use clinical judgement when people request these medicines.’

Lastly, mental health first aid can play a pivotal role. The PSA offers various courses, including Mental Health First Aid (EMPATHISE) and Standard Mental Health First Aid (NSW), which can help pharmacists upskill in this area.

‘We don’t expect pharmacists to replace mental health professionals, but a kind word or caring look from somebody in the pharmacy could be all it takes to break the downward spiral [of] that person about to go home and take a box of Panamax,’ Ms Adamo said.

‘Don’t underestimate your influence.’

‘We’re increasingly seeing incidents where alert fatigue has been identified as a contributing factor. It’s not that there wasn’t an alert in place, but that it was lost among the other alerts the clinician saw,’ Prof Baysari says.

‘We’re increasingly seeing incidents where alert fatigue has been identified as a contributing factor. It’s not that there wasn’t an alert in place, but that it was lost among the other alerts the clinician saw,’ Prof Baysari says.