This summary will present the most up to date findings from a recent Cochrane review.1

Background

It is estimated that a total of 2.8 million people are affected by multiple sclerosis (MS) worldwide. The pooled incidence rate is 2.1 per 100,000 persons/year. The disease is more prevalent in females and the average age of diagnosis is 32 years.2 In Australia, it is estimated that 25,600 Australians live with MS, representing on average more than 10 Australians diagnosed with MS every week. This is also costing the community close to $2 billion.3

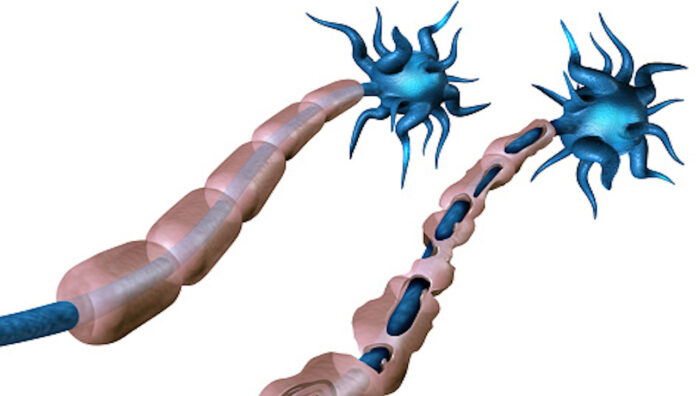

MS is classified as an autoimmune demyelinating disease affecting the central nervous system. It causes neurological relapses and loss of axons, dendrites and neurons. This results in permanent neurological damage to people with MS.1 Clinical symptoms vary depending on the neurones damaged. They range from optic neuritis to weakness, fatigue, cognitive problems, dizziness, pains and spasms, bladder problems and sexual dysfunction.1

Results

- The following databases were searched; Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, the Cochrane Library) (2021 Issue 9); MEDLINE (PubMed) (from 1966); Embase (Embase.com) (from 1974); ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov) for all prospectively registered trials (from 2000);5. World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (apps.who.int/trialsearch) (from 2005). Reference lists of all included articles were also checked as well as personal communication with authors of published and unpublished trials working in the area.

- The primary outcomes measures included the following; number of participants experiencing at least one relapse at 1 year and after, or at the end of the study; number of participants experiencing disability progression at 24 weeks to week 96; number of participants experiencing any adverse event and number of participants experiencing treatment discontinuation caused by adverse events.

- Other outcome measures included changes in quality of life, number of participants with gadolinium-enhancing T1 lesions on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), new or enlarging T2-hyperintense lesions on MRI and changes in brain volume at one year and after or at the end of the study.

- The review included four studies with a total of 2,551 participants. The treatment duration ranged between 24–120 weeks in all studies. Three RCTs compared interferonbeta-1a and ocrelizumab 600 mg for RRMS. For PPMS, one study compared placebo to ocrelizumab 600 mg. Not all the studies reported on the outcome measures of the review.

- Ocrelizumab compared to interferon beta-1a for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis had lower relapse rate (RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.52–0.73), two studies, based on moderate evidence. It also had lower number of participants with disability progression (hazard ratio (HR) 0.60, 95% CI 0.43–0.84), based on two studies with low-certainty evidence and little to no difference in the number of participants with any adverse event (RR 1.00, 95% CI0.96–1.04) based on two studies and moderate-certainty evidence. There was also no or little difference in the number of participants with any serious adverse event (RR 0.79, 95% CI0.57–1.11); based on two studies and low-certainty evidence. The number of participants who discontinued treatment caused by adverse events was lower (RR 0.58, 95% CI 0.37–0.91), based on two studies and low certainty of evidence. The number of participants with lesions was also lower.

- Ocrelizumab compared to placebo for PPMS had lower number of participants with disability progression (HR 0.75, 95% CI 0.58–0.98); based on one study, and low-certainty evidence and a higher number of participants with any adverse events (RR 1.06, 95%CI 1.01–1.11); based on one study and moderate-certainty evidence. There was also little or no difference in the number of participants with any serious adverse event (RR 0.92, 95%CI 0.68–1.23); based on one study and low-certainty evidence. There was no data reported on lesions in any of the participants.

A significant number of patients develop a relapsing-remitting (RRMS) course, which is manifested by deteriorations and remissions. Primary progressive MS (PPMS) is a part of progressive MS phenotypes; it enters a progressive course from onset without a relapsing course.

The current medicines used to treat RRMS include interferon beta-1a, interferon beta-1b, peginterferonbeta-1a, glatiramer acetate, alemtuzumab, natalizumab, mitoxantrone, fingolimod, teriflunomide, dimethyl fumarate and ocrelizumab. Ocrelizumab is the only immunomodulatory agent approved for primary progressive MS (PPMS). This review will present the efficacy and safety for ocrelizumab for the treatment of people with RRMS and PPMS.

Characteristics of the studies

The studies included in the review were randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with blinded assessment of participants, personnel, and outcomes.

They included adults diagnosed with RRMS and PPMS according to a validated criteria taking ocrelizumab with and without other medications, at the approved dose of 600 mg every 24 weeks for any duration, versus placebo or any other active drug therapy.

Participants with other clinically significant autoimmune disorder were excluded.

Quality of the studies

The quality of the evidence for most of the studies was rated as low to moderate due to attrition, indirectness and imprecision.

Conclusion

Based on the published evidence, ocrelizumab reduced relapse rate, disability progression, treatment discontinuation due to adverse events and number of lesions in people with RRMS. For people with PPMS, ocrelizumab reduced disability progression but reported more adverse events than placebo.

Implications for practice and research

Ocrelizumab is clinically beneficial for RRMS and PPMS. It is associated with few adverse events including infusion-related reactions and nasopharyngitis, and urinary tract and upper respiratory tract infections. The results of this review were only based on four studies. Further research should address large studies with a variety of clinical outcomes to show the progression of the disease.

References

- Lin M, Zhang J, Zhang Y, et al. Ocrelizumab for multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2022, Issue 5.

- Walton C, King R, Rechtman L, et al. Rising prevalence of multiple sclerosis worldwide: insights from the Atlas of MS, third edition. Mult Scler 2020 Dec;26(14):1816-21.

- MS Australia. MS on the rise in Australia but still flying under our radar. 2018. At: www.msaustralia.org.au/news/ms-rise-australia-still-flying-radar/

ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR HANAN KHALIL BPharm, MPharm, PhD, AACPA is the Lead of Health Services Administration at Latrobe University. She is also Co-Editor in Chief of the JBI Evidence Implementation.

John Jones MPS, pharmacist immuniser and owner of My Community Pharmacy Shortland in Newcastle, NSW[/caption]

John Jones MPS, pharmacist immuniser and owner of My Community Pharmacy Shortland in Newcastle, NSW[/caption]

Debbie Rigby FPS explaining how to correctly use different inhaler devices[/caption]

Debbie Rigby FPS explaining how to correctly use different inhaler devices[/caption]

Professor Sepehr Shakib[/caption]

Professor Sepehr Shakib[/caption]

Lee McLennan MPS[/caption]

Lee McLennan MPS[/caption]

Dr Natalie Soulsby FPS, Adv Prac Pharm[/caption]

Dr Natalie Soulsby FPS, Adv Prac Pharm[/caption]

Joanne Gross MPS[/caption]

Joanne Gross MPS[/caption]