Pharmacists must put in place controls and tools to minimise data breaches of their electronic systems or they risk fines and reputational damage.

With Australian pharmacies the target of cybercrime in recent months and the full rollout of electronic prescribing looming, pharmacists need to ensure that the privacy of their computer systems is up to date.

Weak links in cybersecurity, particularly with small business and the health sector, has prompted recent focus by the federal government. In May the Prime Minister announced a package of measures totalling $1.35 billion over 10 years including 500 cyber spy jobs after persistent malware attacks by a ‘state actor’ widely believed to be China. Alongside a new awareness of cybercrime at that level, there are also warnings about the need, backed by legislation, for every business to be protected from cyberattack.

Cybercrime can be a significant threat to pharmacy. Ransomware, phishing and scams are tools of the cybercriminal. Data breaches can be malicious and carried out by someone within or outside the pharmacy. They can also be the result of human error or a failure in security systems.

This includes the loss or theft of laptops or storage devices, or paper records which contain personal information such as prescriptions, unauthorised access by an employee, inadvertent disclosure due to human error, or as a disclosure to a scammer as a result of a phishing email.

In June, the Australian Information Commissioner ordered a Victorian GP practice to pay a total of $16,400 to a patient and his husband after a consent form to participate in a HIV transmission-related study was sent in an email to the wrong address after a middle initial was omitted.1

Ransomware

One of the biggest threats to pharmacies, according to Andrew McManus, General Manager, Managed Services at Fred IT Group, is the ransomware attack.

‘Two Australian pharmacies were recently hit,’ he said of attacks in New South Wales and Victoria during the initial COVID-19 restrictions earlier this year.

‘Staff members in each place clicked on legitimate-looking email links, which downloaded the virus software and encrypted the dispensing computers, so the pharmacies were locked out. Then demands for money were made.’

Mr McManus said the ransoms demanded were in bitcoin, both of them in the $5,000–$10,000 range. Bitcoin is most commonly used, he said, and harder to trace with small businesses that include pharmacies because the cybercriminals are beyond the jurisdiction of Australian authorities.

‘The first business, fortunately, did have a backup which was not impacted, and we were able to restore its data locally,’ he said. ‘It was operating again in about 2 hours, with minimal disruption. In the other case, the business had no backup. We were forced to completely wipe the hard drives and reinstall everything – which took a couple of days. The dispensed data was not recoverable, and they had to begin again with a blank database.’

In both instances though, no sensitive information left the pharmacies.

‘Nor was any ransom paid,’ Mr McManus said, ‘although I am aware in other cases, pharmacies in Australia have paid up. We don’t recommend it because there is only a 50–50 chance you will get your data back. It is more likely the cyber criminals will ask for more and more money.’

Mr McManus said the largest ransom he knew of was a demand for more than $20,000 about 2 years ago in Tasmania.

The demand for a larger amount is typical, he says, when the hacker knows the identity of the target, such as a business that values its data, and has the capacity to pay.

Many auto-generated ransomware attacks that target the public demand far less – as low as a few hundred dollars. Members of the public are more prepared to lose their data and don’t have capacity to pay. Pharmacies have fallen victim to these attack types as well.

Phishing

Jennie McDonald, the Director of Security and Compliance Outreach at the Australian Digital Health Agency, says phishing messages are designed to trick you into sharing information, opening an infected attachment or clicking a malicious link.

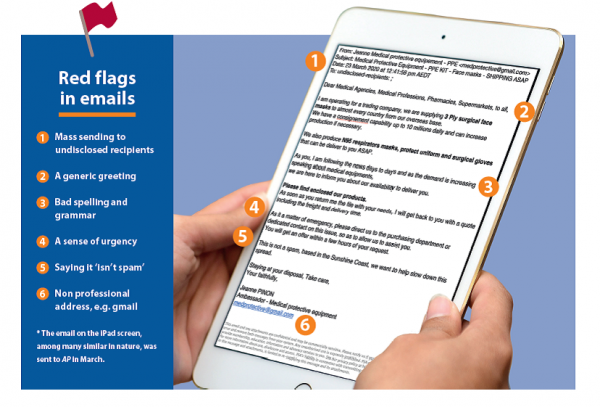

‘Attackers will do their best to make the message seem genuine and may impersonate a business or person that you trust. And while there is no guaranteed way to spot a phishing message, common characteristics can include one or more of six distinct methods (see Box 1).

BOX 1 – Phishing email characteristics

|

Privacy concerns

As online services continue to increase, privacy concerns are paramount, particularly with My Health Record for which nearly all pharmacists now have electronic access, and the recent introduction of electronic prescribing. The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated this uptake.

Pharmacies have been the biggest contributors to My Health Record, uploading on average 4 million documents every month to the start of this year.2 By May this year, a total of 2.05 billion documents had been uploaded into the system – 136 million of them by healthcare providers including pharmacists.4

More than 97% of pharmacies had registered to use My Health Record up to May this year (up 6% since April) and 78% (up 9% in May alone) were using it.3

According to the Australian Cyber Security Centre (ACSC), criminals have taken advantage of the COVID-19 pandemic to step up attacks on healthcare businesses because potential revenue is extremely high and healthcare organisations, such as pharmacies, have critical systems which cannot be off-line.

On average, the ACSC receives about 4,400 cybercrime reports and responds to 168 incidents each month. Since March 2020, it has received more than 95 reports about Australians losing money or personal information to COVID-19 themed scams and online frauds.

A recent ACSC security advisory stated: ‘Sophisticated actors have also been seen undertaking brute force attacks using a trial-and-error method to guess login credentials, and password spray attacks that attempt to access numerous accounts with a list of commonly-used passwords.

Attacks such as these often result in the theft of sensitive data, and underscore the importance of a strong cyber security culture amongst employees. This includes adopting multi-factor authentication, strong password policies, and regular reviews of network logs for signs of malicious activity.’ See Box 2.

BOX 2 – Anti-virus software is not enough

|

When breaking into a computer system, cybercriminals are after three things, according to Mr McManus. They want to:

- steal and resell data

- lock up data so a ransom will be paid to get it back

- steal identities.

For Australian pharmacists, protection of confidential customer information is an obvious priority. Pharmacists are included in the Notifiable Data Breach (NDB) scheme, so must be proactive under the threat of significant fines.

In protecting their information, they are also required by law to let their customers know if data has been compromised. All incidents must be reported to the office of the Australian Information Commissioner.

Andrew McManus says 537 cyber breaches were reported in the final 6 months of 2019. Of those, health was the highest reporting sector (22%). Most breaches came from malicious or criminal attacks (64%), while human error contributed (32%) and system faults (4%).

‘Cyberattacks generally increased 700% between 2018 and 2019, with an estimated cost nationally of $7.8 billion. Almost half of the attacks in 2016 (43%) were directed against small businesses, up from 18% just 5 years earlier. In the first half of 2019, 36% of data breaches (105 out of a total of 289), occurred in the health sector,’ he said.

According to the most recent Australian National Audit Office report, not all healthcare provider organisations achieve minimum cyber security levels. In 2018, according to the report, the private health service provider sector reported the most notifiable data breaches of any industry sector.5

If a pharmacy computer is hacked, there are potentially thousands of people affected, each of whom must be contacted personally or the pharmacy risks serious legal action. The potential for damage to a business reputation is incalculable. A pharmacy, like any other business also faces a fine of up to $2.1 million if it fails to report a breach within 30 days.5

Andrew Matthews MPS, Director of the Medicines Safety Program at the Australian Digital Health Agency, says there are simple steps pharmacies can take to support good security. See Box 3.

BOX 3 – Supporting good securityEvery pharmacy staff member should:

|

‘Start by reading the Information Security Guide for small healthcare businesses and completing the Digital Health Security Awareness eLearning course for people who work in healthcare,’ he said.

‘Organisations that use the My Health Record system also need to develop, implement and maintain a My Health Record security and access policy, to address certain requirements of the legislation.’

Jennie McDonald recommends what she calls a ‘three-two-one’ policy for cyber security. ‘Have three back-ups, in two different formats and keep at least one of the back-ups off-site.’

Australian pharmacists have long been at the forefront of technological change in the healthcare industry. They are on the front line and deal directly with the health outcomes of millions of patients and consumers. To deliver services efficiently and effectively, as well as safely they need to stay ahead of the game with the latest developments in healthcare and use the most up-to-date technology to deliver medicines safely.

Build your skills with PSA Short Courses at www.psa.org.au/psashortcourses

FAQsWhat is a notifiable data breach? When personal information has been accessed by someone unauthorised to do so and the likely result is serious harm to the person who owns the information. What is ransomware? A type of malware (a virus) that encrypts or steals data with the intent to force payment for the decryption keys or its return. Some examples? Well known examples include WannaCry 2017, Petya 2016 (US$60 billion effect alone), Ryuk 2019 and 2020, SamSam 2018. Globally, there are hundreds of variations that have crippling and irrecoverable effect, with damage totally more than US$100 billion in recent years. In Australia, well known recent examples include the Toll Group (twice this year), Service NSW, BlueScope Steel, My Budget, Lion, Fisher & Paykel as well as many smaller businesses. What happens if a pharmacy staff member clicks on a suspicious email? Never click on an email, a link or open a document unless you are 100% certain it is genuine. If you do and suspect it was fake or your computer becomes infected, immediately disconnect that computer from your network, pull out the network cable and/or turn the Wi-Fi or the device off. Contact your IT partner immediately for advice. What if a pharmacist dispenses a prescription to the wrong person? This may be considered notifiable. Seek advice/ become familiar with your obligations as part of the Privacy Act and Notifiable Data Breach (NDB) scheme. You will need to answer whether you can rectify it quickly and reduce/remove any harm to the other person. You have 30 days before you must notify the relevant authorities and individuals. What happens if you open a phishing email targeting personal information or capable of downloading ransomware? Don’t click on it. Be aware of the tell-tale signs. Incorrect spelling or grammar; URL not quite right, it’s unexpected, asking for money or personal information, request is unusual. If you provided personal information, notify the vendor, change password, add multi-factor authentication, notify others who might also be scammed thinking the request is from you. How do you know if data has been breached and, if so, what are your obligations? In many cases cyber data breaches remain undetected for months – until contact by government, media, cyber security companies who find the data on the dark web, or customers who fall victim to its misuse. For prevention, or to slow the breach, consider installing monitoring software to track data movement. From the time of awareness of a breach, you have 30 days to assess whether it is notifiable. You must notify the individuals impacted and the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC). Is it a data breach if a pharmacy staffer hands a patient another’s prescription? Yes. But notifiable? See above – will it result in serious harm to the individual? If you dispense medicines to the wrong patient and then correct it, has there been a data breach by emailing the wrong person? Yes, it is still a data breach. Whether it is notifiable is determined by whether it’s likely to result in serious harm. An accredited pharmacist sends a patient’s HMR report to the wrong doctor. Is that a data breach and, if so, what should happen? If that doctor is not authorised it is still a data breach. See above for whether notifiable. Immediately request the email is permanently destroyed with copies and ask the doctor to confirm destruction. If asked to send a medical history to a hospital pharmacy and you send it to the wrong fax number, what are your obligations? As above, it is a data breach. A community pharmacist sends a medical report to the wrong doctor. Is that a breach, what should happen? Same as the HMR report example (opposite). How to avert disaster when sending by electronic means? Check the ‘send to’ address is correct. Check the information in the body of the email is correct. (Did you copy/paste but forget to change something?) Check attachments are correct. For more information, visit www.oaic.gov.au/privacy/notifiable-data-breaches/when-to-report-a-data-breach/ |

References

- Australian Information Commissioner. ‘SD’ and ‘SE’ and Northside Clinic (Vic) Pty Ltd [2020] AICmr 21 (12 June 2020). At: austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/viewdoc/au/cases/cth/AICmr//2020/21.html

- Australian Digital Health Agency. Update to the My Health Record statistics. 2019. At: digitalhealth.gov.au/news-and-events/news/media-release-update-to-the-my-health-record-statistics

- Australian Government. Australian Digital health Agency. My Health Record statistics. 2020. myhealthrecord.gov.au/statistics

- Australian Cyber Security Centre. Advisory 2020-009: Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) actors targeting Australian health sector organisations and COVID-19 essential services. At: cyber.gov.au/threats/advisory-2020-009-advanced-persistent-threat-apt-actors-targeting-australian-health-sector-organisations-and-covid-19-essential-services

- Office of the Australian Information Commissioner. Notifiable data breaches. At: oaic.gov.au/privacy/notifiable-data-breaches/

- Australian National Audit Office. Implementation of the My Health Record System. Section 3.51 –Cyber security risk context and standards. 2019. At: anao.gov.au/work/performance-audit/implementation-the-my-health-record-system

John Jones MPS, pharmacist immuniser and owner of My Community Pharmacy Shortland in Newcastle, NSW[/caption]

John Jones MPS, pharmacist immuniser and owner of My Community Pharmacy Shortland in Newcastle, NSW[/caption]

Debbie Rigby FPS explaining how to correctly use different inhaler devices[/caption]

Debbie Rigby FPS explaining how to correctly use different inhaler devices[/caption]

Professor Sepehr Shakib[/caption]

Professor Sepehr Shakib[/caption]

Lee McLennan MPS[/caption]

Lee McLennan MPS[/caption]

Dr Natalie Soulsby FPS, Adv Prac Pharm[/caption]

Dr Natalie Soulsby FPS, Adv Prac Pharm[/caption]

Joanne Gross MPS[/caption]

Joanne Gross MPS[/caption]