How digoxin’s narrow safety margin made it the perfect weapon in one of the most prolific hospital killing sprees in history.

In December 2003, Charles Cullen – the nurse employed at various hospitals throughout New Jersey and Pennsylvania – admitted to killing at least 29 people. But the true toll may have been far higher, with estimates suggesting up to 300 victims over a 16- year period.1

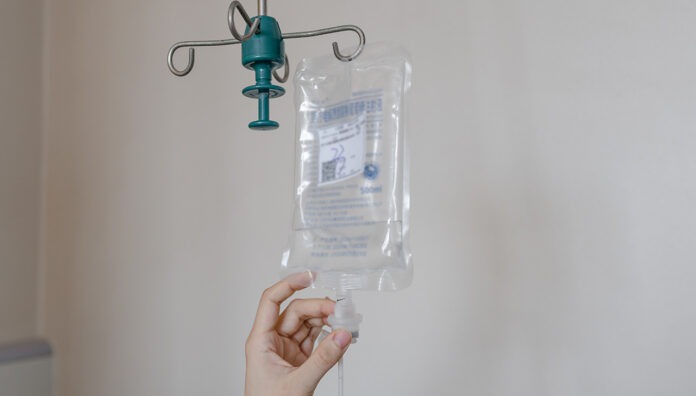

This startling body count makes Cullen ‘perhaps the most prolific serial killer in American history’, writes journalist Charles Graeber. And Cullen’s weapon of choice? Digoxin– injected into as many as three to five intravenous bags per week.1,2

Long before Cullen brought it into the headlines, digoxin – derived from the foxglove plant (Digitalis lanata) – was widely used to treat conditions linked to heart and kidney failure.3

The Greek physicians Dioscorides and Galen both recommended foxglove early in the first millennium, and the Welsh Physicians of Myddvai were formulating foxglove medicines as

early as the 1250s.3–5

However, it was English physician and botanist William Withering who established the elixir’s position as a cornerstone treatment for congestive heart failure and atrial fibrillation. He documented details such as dose and the adverse effects his patients experienced, in a series published in 1785 entitled, ‘An account of the foxglove and some of its medical uses: with practical remarks on dropsy and other diseases’.4–7

Digoxin goes big time

Although Withering made foxglove famous, it remained, as pharmacist Anthony Cartwright notes, a ‘badly controlled’ drug with a ‘low safety margin’.9 Enter Dr Sidney Smith from the Burroughs Wellcome Laboratories. In 1930 he isolated digoxin from Digitalis lanata leaves.4,8

Sold as Lanoxin, digoxin continued to dominate the market for cardiovascular disease therapies. Yet despite its popularity, the drug was not initially approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) until 1954.

Following FDA approval, manufacturers were quick to capitalise on its popularity. By the 1970s there were over 20 brands available worldwide.3,4

In the lab

Unlike most pharmaceutical products that are synthesised in the lab, commercial digoxin is largely old school. It is extracted from foxglove plants and packaged as a tablet or solution.3,11

Classed as a digitalis glycoside, digoxin works by binding to – then inhibiting – the sodium-potassium adenosine triphosphatase pump. This action increases the concentration of sodium within heart cells which, in turn, affects calcium levels. Ultimately, that increases contraction of the heart muscle, thereby lowering the heart rate.12,13

Digoxin today

First listed by the Therapeutic Goods Administration in 1991, digoxin is sold

in Australia as Sigmaxin and Lanoxin.

At roughly $22–$31 per package, it remains an affordable treatment for congestive heart failure and atrial fibrillation.9,10,13

But buyer beware. Digoxin has a narrow therapeutic index – the difference between effectiveness and toxicity is tight. It is estimated that for a 70-kilogram person, a ‘probable human oral lethal dose’ is less than 5 mg/kg.3,14

Cullen’s index

Cullen’s fate, like digoxin’s action, required precise calibration. He negotiated 11 consecutive life terms, avoiding the death penalty. However, Cullen then refused to attend his sentencing unless he was allowed to donate a kidney to save a friend’s relative.1,2

As Cullen’s lawyer commented, ‘I know there’s a certain amount of irony involved here.’2

References

- Smothers R. Judge sets conditions to allow serial killer to donate kidney. New York Times, 18 March 2006.

- Ramirez. Killer donated his kidney, lawyer says. New York Times, 20 Aug 2006.

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Database. Digoxin CID 2724385.

- Cartwright AC. The British Pharmacopoeia, 1864 to 2014: Medicines, international standards and the states. London, Routledge 2016.

- Lewis LD. Early human studies of investigational agents: dose or microdose? Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009 Mar;67(3):277–9.

- Whayne TF Jr. Clinical use of digitalis: a state of the art review. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2018 Dec;18(6):427–440.

- Semsaian C. Digoxin in the 21st century. Aust. Prescr. 1999;22(6):136–7.

- Smith S. Digoxin, a new digitalis glucoside. J. Chem. Soc. 1930:508–510.

- Australian Government. Therapeutic Goods Administration. LANOXIN PG digoxin 62.5microgram tablet bottle (11108).

- Australian Government. Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. Digoxin.

- Hogue C. Digoxin: Purpose: cardiac drug. C&EN. 2017;83(25).

- CHEMEUROPE.COM. Digoxin.

- WebMD. Digoxin – uses, side effects, and more.

Owner of Canberra's Capital Chemist Southlands Louise McLean MPS.[/caption]

Owner of Canberra's Capital Chemist Southlands Louise McLean MPS.[/caption]

Supplied by CSL Seqirus[/caption]

Supplied by CSL Seqirus[/caption]

Tahnee Simpson[/caption]

Tahnee Simpson[/caption]

Nicolette Ellis MPS[/caption]

Nicolette Ellis MPS[/caption]