One in six Australian pharmacists are pro-life and oppose elective termination of pregnancy. But this does not diminish their responsibilities to patients.

Marie enters your pharmacy and hands you a prescription for MS-2 Step. You can see that she has been crying and has her five-year-old daughter with her. You know that one of the active components of MS-2 Step is colloquially known as the ‘abortion pill’ or RU486. You believe abortion should be illegal and have a conscientious objection to it based on your religious beliefs. You tell Marie that you are unable to supply her with the medication. Marie tells you through tears that her doctor recommended this medication for her. You still refuse to dispense the medication and Marie leaves.

What you didn’t find out was that Marie’s pregnancy is not viable because of severe foetal abnormalities, and she was informed by her doctor that the medical method is a less invasive way to remove the foetus. This pregnancy was wanted; Marie had been through in-vitro fertilisation (IVF) to achieve the pregnancy but it had not progressed. Marie had experienced a previous miscarriage and was being monitored weekly.

Media and misconceptions

Unfortunately, this hypothetical scenario (in this example) can be close to reality. Mid-2018, a report in the Australian media identified a similar case1 that occurred in the United States whereby a woman was denied the medication she required to end her unviable pregnancy. The relevant State Pharmacy Board is investigating.

Recently, a NSW woman used MS-2 Step supplied via telehealth but it did not have the expected result of ending her pregnancy (a very rare incident that occurs in <1% of cases).2 A continuing pregnancy following administration of this therapy may result in fetal anomalies. She was denied local hospital care for a D&C (dilation and curettage) and had to drive six hours both ways to attend a large tertiary hospital to manage the complication of a termination of pregnancy. A health professional asked the question, ‘Whose values and morals does this woman have to abide by?’

The continued stigmatisation of abortion indicates that, for many Australian women, the decision to have and seek access to an abortion is heavily influenced by the perception and knowledge of their trusted health professional.

The statistics

By their mid-30s, one in six (16%) of Australian women report having at least one abortion in a longitudinal study on women’s health.3 Women who were in a de facto relationship, were single or divorced were more likely to have an abortion than their married counterparts.3

There is concern that abortion is illegal and this remains the case in New South Wales (Queensland recently achieved law reform to remove abortion from the criminal code). The Australian Capital Territory and South Australia specify that abortions must be performed in an approved medical facility.4 A woman and her doctor can be convicted for unlawful abortion in NSW, punishable by up to 10 years in prison under the Crimes Act 1900.5 However, if two doctors are of the opinion that continuing pregnancy would be seriously harmful to the health of the woman, abortion is considered lawful according to case law. Recent law reform attempts in 2017 were defeated in the NSW Parliament.5

More than three-quarters of respondents in a NSW survey were unaware that abortion was a criminal offence in their state.5 The majority of Australians (87%)6 support laws allowing women access to safe and legal abortions, with 73% suggesting it should be decriminalised in NSW.5

Recent research identified that women with less control over their reproductive health – whether through family violence, drug use or ineffective contraception – are more likely to terminate a pregnancy.3 Women who already have children are also more likely to have a termination than those who haven’t. More regional and rural residents (53%) reported knowing someone that had previously had an abortion compared to their metropolitan (46%) counterparts.5

Fundamental access issues, including geographical isolation, financial barriers and lack of knowledge around options, restrict method choice for pregnancy termination.7 A telemedicine medical abortion service demonstrated a safe, satisfactory and inexpensive supply option, particularly in areas of Australia where abortion facilities were lacking.4

Ethical/conscientious objection

PSA’s Code of Ethics Care Principle 2 states a pharmacist ‘informs the patient when exercising the right to decline provision of certain forms of health care based on the individual pharmacist’s conscientious objection, and in such circumstances, appropriately facilitates continuity of care for the patient’.8 Conscientious objection is defined as ‘a practitioner’s refusal to engage or provide a service primarily because the action would violate their deeply held moral or ethical value about right and wrong’. Continuity of care is particularly important when conscientious objection to the supply of an abortifacient occurs in the community pharmacy setting.

An Australian study demonstrated that pharmacists state a lack of knowledge about the supply of medical termination of pregnancy (MTOP), privacy concerns and complex jurisdictional legalities as additional reasons to the non-supply of MTOP.9 Our yet-to-be published research, conducted via an online questionnaire, demonstrated that one in six pharmacists consider themselves pro-life, or oppose elective abortion. Evidence of stigma around the use of MTOP was apparent in the free-text response sections of the questionnaire.

MS-2 Step

Medical termination of pregnancy, or MTOP, is well established, safe and effective. In 2012, mifepristone became widely available in Australia via MS Health (23 years after the drug was first approved in France).4 In 2013, mifepristone and misoprostol were added to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) as two separate products. A PBS update in 2015 approved the combination product MS-2 Step for use in gestations up to 63 days.

MS-2 Step contains 1 x 200 mg mifepristone (green pack) and 800 microgram (4 x 200 mcg) misoprostol (purple pack). The composite pack is still approved for use in gestations up to 63 days (9 weeks). Mifepristone is also widely known as RU486.

Informed consent for MTOP treatment must be obtained by the prescriber from the patient and she is able to decide against this treatment at any time. Decision-making includes an exploration of all options, including continuing the pregnancy, fostering and adoption. Surgical termination is also offered as an alternative option to this treatment by the medical practitioner. Further counselling or referral will be considered if it is deemed necessary.

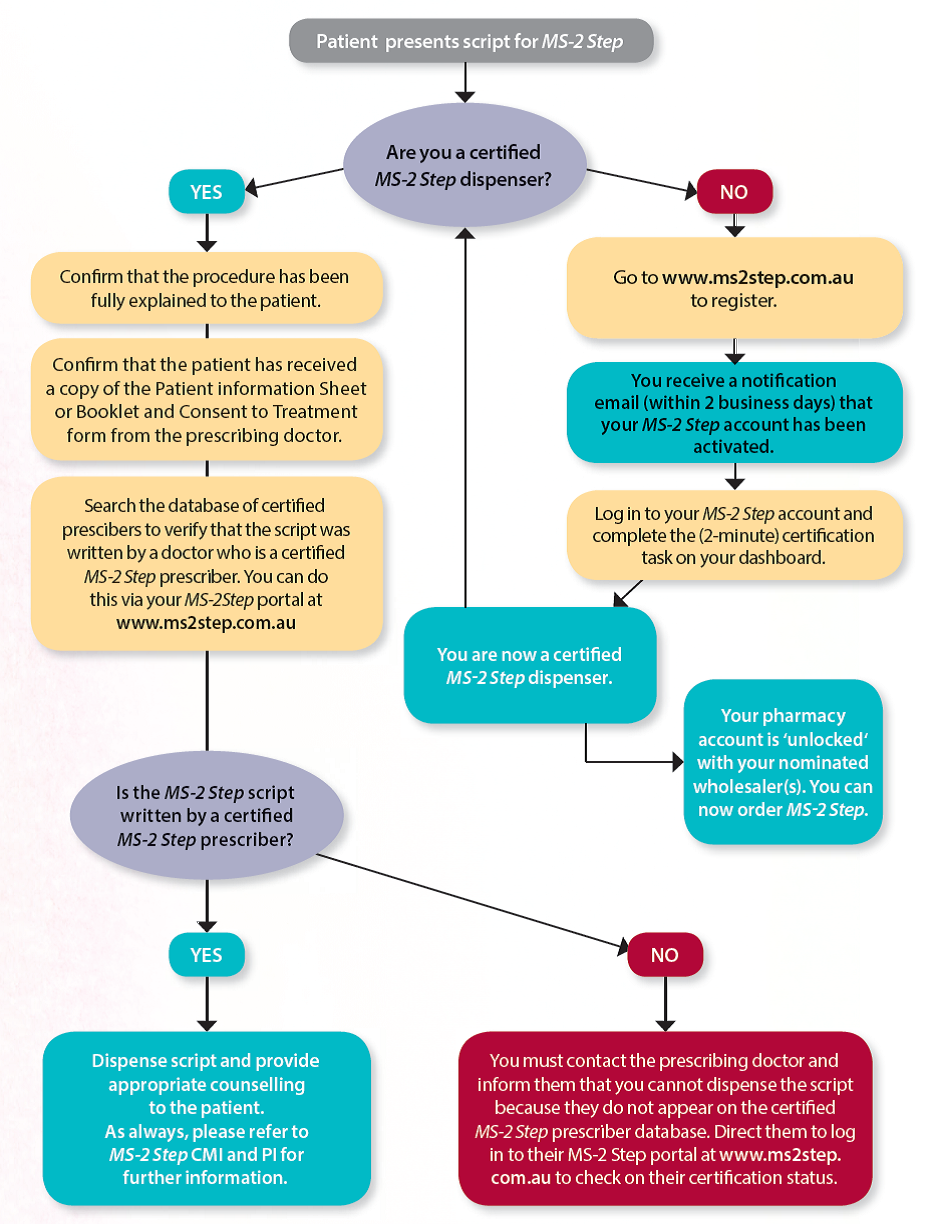

The prescriber is required to be certified by MS Health in order to write a prescription for MS-2 Step. The pharmacist must be a certified MS-2 Step dispenser to order and supply the medication in a pharmacy. It is important to note that this certification is pharmacist-specific rather than pharmacy-specific, so every pharmacist that dispenses MS-2 Step in a particular pharmacy is required to be certified with MS Health.

Any pharmacist can register to be a certified MS-2 Step dispenser (at www.ms2step.com.au). The registration process is quick, simple and requires the applicant to input their specific pharmacy details as well as the account details of their preferred wholesaler. This information then allows MS Health to ‘unlock’ their pharmacy account with the nominated wholesaler, thus enabling the pharmacy to place an order for MS-2 Step.

Once the pharmacist’s application is approved by MS Health, they are required to log in to their MS-2 Step account and complete a simple certification task. Pharmacists are not required to complete any specific training in order to gain certification but the online Medical Education Program is available on the MS-2 Step portal and should be utilised for self-education. The Medical Education Program provides comprehensive information beyond what is available in the PI or CMI for MS-2 Step. It outlines practice points, and touches on issues of ethical and professional accountability. It is recommended reading.

Pharmacology and mechanism of action (MOA)

Mifepristone (progesterone receptor antagonist) is metabolised by CYP3A4 and blocks the action of progesterone, thereby stopping the pregnancy from growing, causing the placenta and embryo to detach from the uterine lining, and dilates the cervix. The drug also sensitises the uterus to the action of prostaglandins 36 to 48 hours after oral dosing. Misoprostol is dosed buccally 36 to 48 hours after mifepristone.

Misoprostal causes the uterus to contract, expelling the uterine contents with accompanying cramping and bleeding.

As per the Product Information for MS-2 Step, this regimen has a success rate of 93%, with continuing pregnancy or incomplete abortion occurring in 7% of cases. However, recent research has shown that the overall efficacy of mifepristone following by buccal misoprostol sits at 96%.4,10

There are reports of foetal malformations following administration of misoprostol. The data on malformations following foetal exposure to mifepristone alone are too limited to establish it as a human teratogen. Haemorrhage or infection may occur in <0.1% of cases.

Fertility may return less than two weeks following the administration of MTOP, so future contraceptive options should also be discussed. MTOP can be safely offered to women who have had a caesarean section, multiple gestations, are obese or have uterine abnormalities (including fibroids). MS-2 Step should be avoided during breastfeeding.

Mifepristone is not recommended (due to a lack of studies) in patients with:

- cardiovascular disease

- hypertensive disease

- hepatic disease

- respiratory disease

- renal disease

- diabetes

- severe anaemia

- malnutrition

- heavy smokers.

Contraindications to treatment include:

- lack of access to medical care in the 14 days post-treatment

- suspected or confirmed ectopic pregnancy

- uncertainty about gestational age

- chronic adrenal failure

- severe disease required exogenous steroid administration (efficacy may be reduced for 3–4 days following administration of mifepristone)

- known or suspected haemorrhagic disorders or treatment with anticoagulants

- known hypersensitivity to the active drug or excipients in each formulation

- contraindication to mifepristone

- contraindication to misoprostol.

Required counselling

The composite pack should be stored below 25 degrees Celsius. The patient should take mifepristone 200 mg orally with a glass of water. Between 36 and 48 hours later, the patient should take misoprostol 800 mcg as a single dose by placing 4 tablets between the cheek and gum for at least 30 minutes. Any remaining residue after this time can be swallowed with water.

Possible side effects of treatment include bleeding and cramps, nausea and vomiting, diarrhoea and fever/chills. Bleeding and cramps start within 4 hours of misoprostol administration although it may start following administration of mifepristone. Bleeding is not proof of complete expulsion of the pregnancy and must be confirmed at a follow-up appointment via a blood test or ultrasound. Patients should be advised to rest, use heat packs and massage on the lower abdomen, and use pain relievers as required. Paracetamol alone is ineffective, with NSAIDs the most effective option for pain relief. An anti-emetic may also be taken if required. A support person is highly recommended during the process.

Over 90% of women (n = 6265) who took MS-2 Step reported that the experience was as they expected or better.11 The same proportion would recommend this method to friends.11 There is 24-hour nurse telephone support available (1300 515 883), and follow-up care to confirm termination of pregnancy and exclude complications occurs in each case.

Further resources

- For further information about MS-2 Step or to register as a dispenser, go to: www.ms2step.com.au

- Australian Medicines Handbook 2019 – mifepristone and misoprostol monographs

- Family Planning Alliance Australia at: www.familyplanningallianceaustralia.org.au

- Marie Stopes Australia at: www.mariestopes.org.au

- Children by Choice: www.childrenbychoice.org.au

References

- ABC news online. US pharmacist denies woman abortion medicine based on ‘moral objection’. 2018. At: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-06-26/pharmacist-denies-woman-miscarriage-drug-on-moral-grounds/9910166

- Rushton G. A woman was turned away from a hospital after a failed medical abortion. 2019. At: https://www.buzzfeed.com/ginarushton/nsw-abortion-woman-turned-away-hospital

- Taft AJ, Powell RL, Watson LF, Lucke JC, Mazza D, McNamee K. Factors associated with induced abortion over time: secondary data analysis of five waves of the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2019;0(0). At: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30727034

- Hyland P, Raymond EG, Chong E. A direct‐to‐patient telemedicine abortion service in Australia: Retrospective analysis of the first 18 months. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2018;58(3):335-40. At: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29603139

- Barratt A, McGeechan K, Black K, Hamblin J, de Costa C. Knowledge of current abortion law and views on abortion law reform: a community survey of NSW residents. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2019;43(1):88-93. At: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1753-6405.12825

- De Crespigny LJ, Wilkinson DJ, Douglas T, Textor M, Savulescu J. Australian attitudes to early and late abortion. Medical Journal of Australia. 2010. p. 9-12. At: https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2010/193/1/australian-attitudes-early-and-late-abortion

- Shankar M, Black KI, Goldstone P, Hussainy S, Mazza D, Petersen K, et al. Access, equity and costs of induced abortion services in Australia: a cross-sectional study. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2017;41(3):309-14. At: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28110510

- Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. Code of Ethics for Pharmacists. 2017. At: https://www.psa.org.au/membership/ethics/

- Lee RY, Moles R, Chaar B. Mifepristone (RU486) in Australian pharmacies: the ethical and practical challenges. Contraception. 2015;91(1):25. At: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25248673

- Chen MJ, Creinin MD. Mifepristone With Buccal Misoprostol for Medical Abortion: A Systematic Review. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2015;126(1):12-21. At: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26241251

- Goldstone P, Michelson J, Williamson E. Early medical abortion using low‐dose mifepristone followed by buccal misoprostol: a large Australian observational study. Medical Journal of Australia 2012;197(5):282-6. At: https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2012/197/5/early-medical-abortion-using-low-dose-mifepristone-followed-buccal-misoprostol

Learn more at www.australianpharmacist.com.au

John Jones MPS, pharmacist immuniser and owner of My Community Pharmacy Shortland in Newcastle, NSW[/caption]

John Jones MPS, pharmacist immuniser and owner of My Community Pharmacy Shortland in Newcastle, NSW[/caption]

Debbie Rigby FPS explaining how to correctly use different inhaler devices[/caption]

Debbie Rigby FPS explaining how to correctly use different inhaler devices[/caption]

Professor Sepehr Shakib[/caption]

Professor Sepehr Shakib[/caption]

Lee McLennan MPS[/caption]

Lee McLennan MPS[/caption]

Dr Natalie Soulsby FPS, Adv Prac Pharm[/caption]

Dr Natalie Soulsby FPS, Adv Prac Pharm[/caption]

Joanne Gross MPS[/caption]

Joanne Gross MPS[/caption]