To coincide with Women’s Health Week, 6–10 September, we explore why women’s health is often minimised, or normalised, and how pharmacists can help.

The snapshot of women’s health in the National Women’s Health Strategy 2020–2030 makes sobering reading for health professionals.1

Women at all stages of life are at greater risk than men of mental ill-health. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women experience higher rates of co-morbid conditions, including diabetes and breast, cervical and ovarian cancers, than non-Indigenous women.

Some 87% of women aged 65 and over have a chronic disease. Women are 1.6 times as likely as men to suffer from co-existing mental and physical illness.

Symptoms of a heart attack in women are less likely to be recognised than in men, and they are also less likely to receive appropriate treatment.2

Women and girls with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) are diagnosed later in life than males.3 This is due to specific barriers including gender biases from stereotypical expectations such as the perception that it primarily affects males – the ‘disruptive boy’. As well there is a dearth of research on the life-span experiences of females with ADHD, with the last meta-analysis of gender differences published at least 15 years ago.3

Normalising chronic pain

Gabrielle Jackson, a journalist and author, was nearing her 40s when she discovered she wasn’t a hypochondriac.

She’d suffered various health problems for years but not wanting to appear ‘weak’, and led to believe medicine could do no more than help with the contraceptive pill, had ‘normalised’ most of it. Her GP told her ‘some women have bad period pain, that’s life’.4 She believed her constant back and hip aches were from that skiing accident when she was 19. But, after a bad flare-up of her myriad symptoms in her 20s, she attended an endometriosis conference.

‘All the things wrong with me – the period pain, leg pain, back pain, hip pain, shooting pains up my rectum and vagina, bloating, nausea, diarrhoea, stomach upset, dizziness, and the oh-so-debilitating fatigue’ – were, she learned there, common symptoms of endometriosis.5 As she relates in her widely read 2019 book Pain and Prejudice, Ms Jackson also heard about adenomyosis for the first time at that conference – and was diagnosed with it later the same year.5

What does this say about the health profession and the silent suffering that women, most often, bear?

In times gone by, women were labelled ‘hysterical’, diagnosed with neurasthenia, a term retired from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, which meant fatigue after mental or physical effort, or extreme lassitude, or told their pain threshold was lower than normal. Today, women’s symptoms of ill-health are normalised, dismissed or not accepted at face value. And their continued suffering remains unseen, often with no plan afterward with unsuccessful treatment. But the bias is more subtle and usually subconscious.

‘Women experience a lot of gender disparity,’ says PSA General Manager Knowledge Development and State Manager, Victoria Stefanie Johnson. ‘We tend to think of cardiovascular disease, for example, as a men’s problem. But cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in women, and symptoms often present differently to men.’

Women’s health research lacking

‘Women make up half of the world’s population and yet medical research has largely been conducted by men, on men and for men,’ writes Professor Kate Leslie of the University of Melbourne.6

A recent Australian Institute of Health and Welfare7 report says Australian women are more likely than men to experience sexual violence and to have multiple chronic conditions.

A recent Australian Institute of Health and Welfare7 report says Australian women are more likely than men to experience sexual violence and to have multiple chronic conditions.

Almost half of the 12.6 million female population has one or more chronic conditions, ranging from obesity, arthritis, asthma, heart disease and stroke, to mental health conditions.

In a recent submission to the federal government, Pain Australia said Australian women are over-represented in poor health outcomes across several significant areas, impacting on their role as carers and leading to social and economic exclusion.8 Yet for a host of issues, the age at first diagnosis is typically lower for men compared to women, according to a recent study in Nature Communications.9 This is despite men waiting longer to seek medical attention and less frequently than women. 10

‘Women wait longer for pain medication than men, wait longer to be diagnosed with cancer, are more likely to have their physical symptoms ascribed to mental health issues, are more likely to have their heart disease misdiagnosed or to become disabled after a stroke, and are more likely to suffer illnesses ignored or denied by the medical profession,’ according to Gabrielle Jackson’s research.5

Figure 1 – Do we feel heard? The answer is no

| A recent ABC Australia Talks Survey asking whether people’s health concerns had ever been dismissed by a doctor found that only 46% of women have confidence in Australia’s health. Many do, indeed, feel ignored.

Interviewed in response, GP Dr Karen Magraith told the ABC that more women tend to have their health concerns dismissed by GPs ‘and this is because medicine historically has been viewed from a male perspective.’ ‘Women with heart disease tend to have their condition diagnosed later and don’t receive as much evidence-based treatment as men do. That may be because research has mostly been done in men’s heart disease, whereas women present a little differently,’ Dr Magraith said. ‘In my area of interest [menopause], we have women with a variety of different health concerns. Menopause is not just when women’s periods stop. There are a range of concerns such as gynaecological, psychological, hormonal and other issues that need a comprehensive assessment and an individualised plan. It takes time to do this. It’s a complex consultation, sometimes needing more than one consultation. ‘There are financial disincentives for providing comprehensive care in general practice. Many women find it difficult to access longer consultations, either through a lack of availability of long appointments or an inability to afford gap payments.’ Dr Magraith said mental healthcare is another area where people need longer consultations. ‘There is more support for me to do a quick procedure than there is for me to support adolescent mental healthcare.’ |

Diagnosis can take years

‘Patients with endometriosis have been waiting between seven and 12 years for a diagnosis,’ says Director and Co-Founder of Endometriosis Australia Donna Ciccia.

While a recent study11 indicates that has reduced to 6.5 years since 2013, Ms Ciccia says that remains a considerable wait for a lifelong condition that can begin at age 8.

‘Chronic pain impacts on the daily lives of so many Australian women, who are often stigmatised and have their pain dismissed, with very little understanding and research into pain conditions, including period pain and endometriosis,’ says Pain Australia’s CEO Carol Bennett.

In fact, it took until 2011 for the National Academy for Medicine in the United States to declare that chronic pain – rather than acute pain (the one that medical science has largely focused on) was a disease condition that needed to be treated as a separate entity which could also result in psychological and social consequences, including depression, anxiety, anger, fear and reduced capability in carrying out roles such as employee, friend and family member.12 And despite the fact that women and some non-binary people will eventually enter menopause, education and treatment remains inconsistent. And despite years of change, there remain hidden disparities and unconscious bias between genders.

Researching her book, Ms Jackson found that ‘there are 10 chronic pain conditions that predominantly affect women which have very similar symptoms; and that once a person has one, they’re more likely to accumulate others. Endometriosis, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, painful bladder syndrome, migraine headache, chronic tension-type headache, temporomandibular joint disorders, chronic lower back pain and vulvodynia affect at least 50 million women (in the United States) alone.’4

‘Why are women still being treated as hysterical, overly emotional, anxious and unreliable witnesses to their own wellbeing?’ she asked as her book was published, and why aren’t they trusted with what they tell health professionals? ‘The answer turns out to be quite simple. They don’t really know much about us,’ she found.12

‘Why are women still being treated as hysterical, overly emotional, anxious and

unreliable witnesses to their own wellbeing?’

Professor Susan Davis is Head of Women’s Health Research at Monash University and President of the International Menopause Society.

‘The gynaecologist thinks it’s the GP’s problem, and GPs think it’s the gynaecologist’s problem,’ she says. ‘No-one wants to treat the women.’

Professor Davis says menopause health checks should be tied to biological age not chronological age.

‘A Medicare-related health check for midlife for women needs to be anchored to when they hit menopause, with an appropriate time allocation to look at preventing chronic disease, disability and bone health,’ she says. Professor Davis would like to see a Menopause Action Plan, similar to the $4 million National Plan for Endometriosis introduced in 2017.

Box 1 – Supporting women in the pharmacy

Reducing unconscious bias is multifactorial and complex. Stefanie Johnston MPS suggests the following as starting points.

|

National action plans and strategy

The Federal Government has pledged $52.2 million over 3 years for a National Women’s Health Strategy 2020–2030.

Priority areas include maternal, sexual and reproductive health, healthy ageing, chronic conditions and preventive health, mental health and the health impacts of violence against women and girls.

The Federal Government has also earmarked another $8.58 million for an Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health, the largest health survey in Australia, in partnership with the Universities of Queensland and Newcastle. In May, it launched a world-first National Strategic Action Plan for Pain Management, developed by Pain Australia.

Stefanie Johnston is also PSA’s representative in SPHERE (Sexual and Reproductive Health for Women in Primary Care), a new collaborative network of experts and researchers that aims to transform the delivery of sexual and reproductive healthcare services to women. It is a 5-year program funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council.

Ms Johnston says the changing demographics of the health professions, which are now younger and increasingly female, may result in a changed experience moving forward. Access, however, remains the biggest systemic barrier.

‘We have issues of access in remote and regional areas, and we have barriers to access from a cost perspective, as a substantial amount of the system is fee for service,’ says Ms Johnston.

Telehealth, practitioners agree, partly solves the problem, but some issues, like sexual health matters for women of different cultural backgrounds, need to be discussed in privacy and face to face.

Where to next?

While women’s health is occupying a more prominent place on the national agenda, much remains to be done.

The health system, including pharmacists, needs to do better to root out systemic bias in relation to gender differences on health issues, including pain.

Strategies such as the National Strategic Action Plan on Pain Management and the National Women’s Health Strategy recognise the importance of gender equity with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island women and culturally and linguistically diverse women, and others, listed as priority groups under the strategy.

Through initiatives such as SPHERE, PSA will ‘help advocate for more innovative and evidence-based primary care solutions to boost the capacity, quality and safety of women’s sexual and reproductive health’, says Stefanie Johnston.

‘The PSA considers these issues in the planning and development of its educational offerings for pharmacists.

‘Across the organisation we are committed to helping practitioners reflect on unconscious or systemic biases that women experience and support pharmacists to remove barriers to effective and appropriate care,’ Ms Johnston said.

‘I urge all pharmacists to consider if there is more they can do to support patients as part of their regular, ongoing practitioner development.’

|

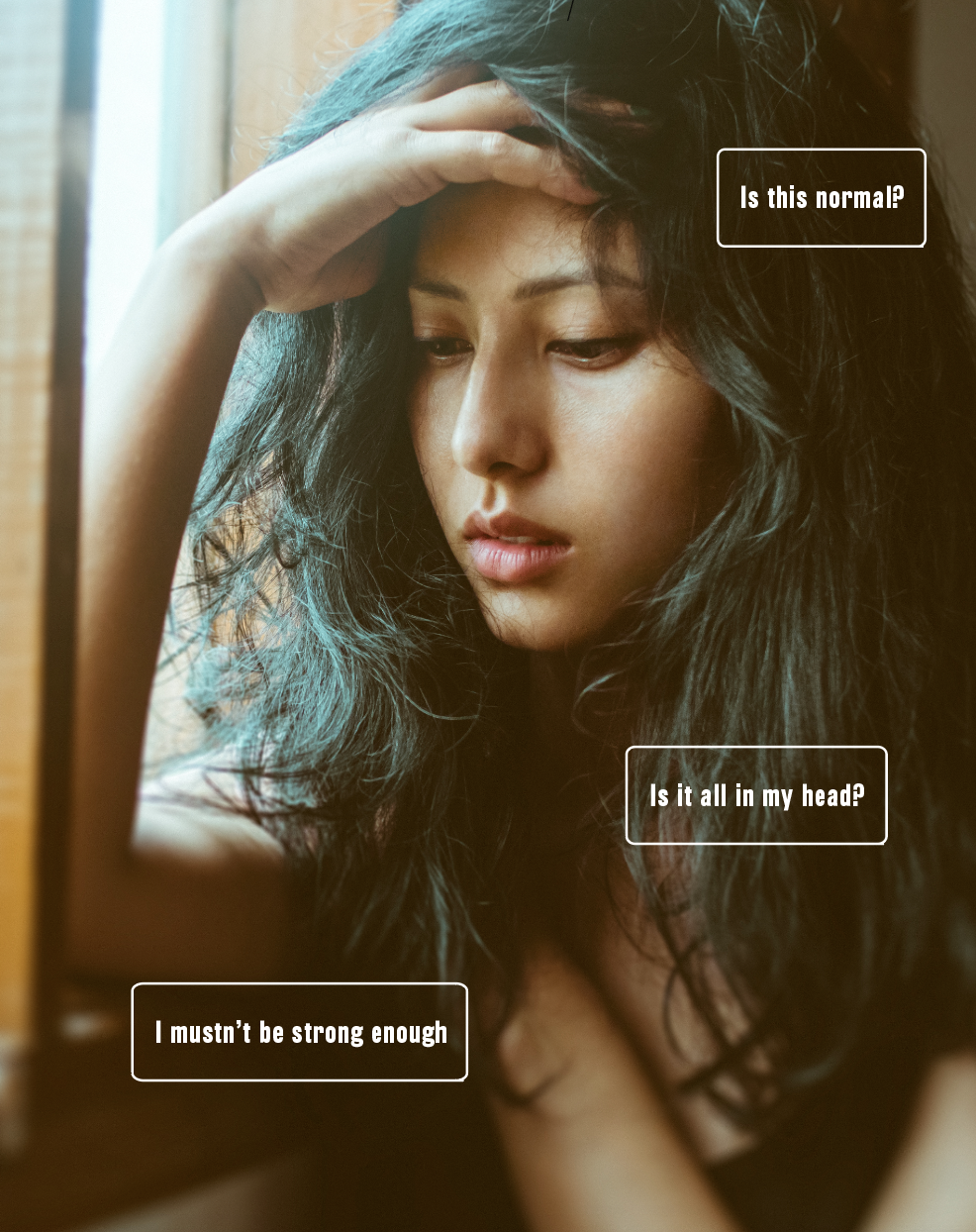

Bridget Hustwaite, endometriosis warrior  At 15 years old, Triple J radio presenter Bridget Hustwaite visited her local general practitioner with severe period pain. ‘I wasn’t told about endometriosis,’ she recalls. And with no scans or tests ordered, the doctor sent her packing with a prescription for the pill. And while the pill did not work, ‘I was made to feel that what I was experiencing was normal, so I didn’t seek another opinion for a number of years.’ Her low-income job in Melbourne made her put off another GP’s recommendation to see a gynaecologist. But with money later saved, she saw a GP who she’d been told was ‘good with women’s health issues’. Yet that GP in Ms Hustwaite’s home town of Ballarat ‘flat out’ told her she didn’t have endometriosis and that many women had it worse than her, she told AP. ‘It was pretty crushing’ and Ms Hustwaite’s ‘worst experience with a medical professional’. ‘She decided that my pain wasn’t serious enough to see a gynaecologist,’ says Ms Hustwaite, now the author of How to endo: a guide to surviving and thriving with endometriosis. In 2018, after moving to Sydney and finding another women’s health doctor 12 years after that first GP consultation, her symptoms such as pain during sex and also when urinating and emptying her bowels were finally diagnosed as stage 4 endometriosis, where endometrium tissue grows outside the uterus and can affect fertility. Had she not been diagnosed, Ms Hustwaite says she would have lost parts of her bowel. She has now undergone two rounds of excision surgery and is ‘looking good fertility-wise’. Ms Hustwaite has set up an Instagram page and rallied an army of ‘endo warriors’ to carry the message out into the community. ‘I really wanted to write the kind of book that 15-year-old Bridget so desperately needed when she started experiencing painful periods. At that time, endometriosis was not a public conversation, let alone in my vocabulary,’ she says. ‘It really has only been in recent years that we have seen more awareness and conversation surrounding this chronic illness.’ She wishes endometriosis had been included in her high school health curriculum, which may have allowed her to better advocate for herself and ask more direct questions as a teenager. ‘My lengthy diagnosis journey has definitely had an impact on my mental health, as it made me question my own pain tolerance and whether it was actually all in my head. ‘This in turn created a lot of negative self-talk and worth, and it’s something I’m still working on to this day,’ she says. |

References

- Australian Government Department of Health. National Women’s Health Strategy 2020–2030. 2019. At: www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/national-womens-health-strategy-2020-2030

- Khan E, Brieger D, Amerena J, et al. Differences in management and outcomes for men and women with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Med J Aust 2018;209(3)118–123.

- Young S, Adamo N, Ásgeirsdóttir BB, et al. Females with ADHD: an expert consensus statement taking a lifespan approach providing guidance for the identification and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in girls and women. BMC Psychiatry 2020;20:404.

- Jackson G. I’m not a hypochondriac. I have a disease. All these things that are wrong with me are real, they are endometriosis. Guardian. 2015 September 28. At: https://bit.ly/3m9jFiI

- Jackson G. Pain and prejudice. Sydney. Allen & Unwin. 2019.

- Leslie K. Why are women ignored by medical research? Pursuit 2019. At: https://pursuit.unimelb.edu.au/articles/why-are-women-ignored-by-medical-research

- Australian Government Institute of Health and Welfare. The health of Australia’s females. 2019. At: www.aihw.gov.au/reports/men-women/female-health/contents/who-are

- Pain Australia. Establishing a national women’s health strategy for 2020 to 2030. 2018. At: www.painaustralia.org.au/static/uploads/files/establishing-a-national-womens-health-strategy-for-2020-to-2030-wfqyiuhoddoa.pdf

- Westergaard D, Moseley, Sorup FKH, et al. Population-wide analysis of differences in disease progression patterns in men and women. Nature Communications 2019;10(1):666.

- Cowie T. Men’s health, the other gender gap. Australian Pharmacist 2020:39(6):20–5.

- Armour M, Sinclair J, Ng CHM, et al. Endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain have similar impact on women, but time to diagnosis is decreasing: an Australian survey. Sci Rep 2020. Epub 2020 Oct 1.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Advancing Pain Research, Care, and Education. Relieving Pain in America. 2011. p 32.

- Jackson G. Why don’t doctors trust women? Because they don’t know much about us. Guardian 2019 September 2. At: https://bit.ly/2W3UanR

John Jones MPS, pharmacist immuniser and owner of My Community Pharmacy Shortland in Newcastle, NSW[/caption]

John Jones MPS, pharmacist immuniser and owner of My Community Pharmacy Shortland in Newcastle, NSW[/caption]

Debbie Rigby FPS explaining how to correctly use different inhaler devices[/caption]

Debbie Rigby FPS explaining how to correctly use different inhaler devices[/caption]

Professor Sepehr Shakib[/caption]

Professor Sepehr Shakib[/caption]

Lee McLennan MPS[/caption]

Lee McLennan MPS[/caption]

Dr Natalie Soulsby FPS, Adv Prac Pharm[/caption]

Dr Natalie Soulsby FPS, Adv Prac Pharm[/caption]

Joanne Gross MPS[/caption]

Joanne Gross MPS[/caption]