Kylie van Rooijen MPS found a role in a South Australian Aboriginal health service by chance. After seeing the difference having a pharmacist on board can make, they are determined to keep her on.

While participating in the Port Lincoln Pharmacist in General Practice project, funded by Country SA Primary Health Network and PSA, Ms van Rooijen was initially working at a mainstream health service.

But when her husband, who is a doctor at Port Lincoln Aboriginal Health Service, told the clinical manager about Ms van Rooijen’s GP pharmacist role, the manager was intrigued.

‘She said, “oh that sounds really good, how do we get one of those?”,’ Ms van Rooijen told Australian Pharmacist.

The project is now nearing completion, but Ms van Rooijen will have an ongoing role at the clinic due to the impact she has had on their patients and practice.

‘They extended their budget on my behalf by looking for external funding to put me on for 2 days a week, which is amazing,’ she added.

Making inroads

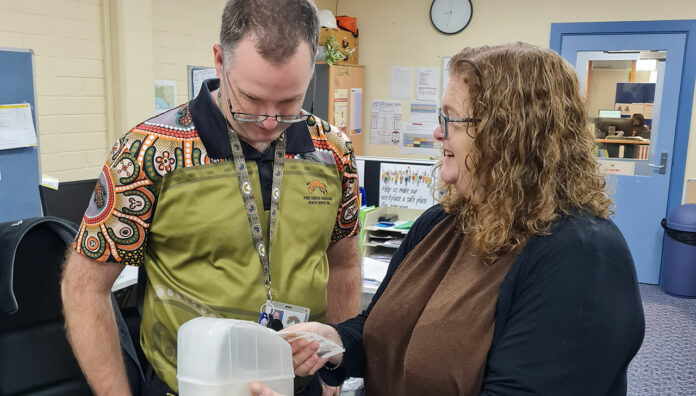

From the outset, Ms van Rooijen began with audits, analysing patient history and medicine reconciliations to get a handle on the clinic’s needs, and where they might best be able to use her services and knowledge.

‘They extended their budget on my behalf by looking for external funding to put me on for 2 days a week, which is amazing.’

She built relationships with the clinic’s staff, who now use her as a sounding board for any medicine-related questions, as well as a resource for patients around medicine education.

‘On a typical morning, my inbox is full of hospital discharges with medicine changes, so I’ll do some reconciliation with our records,’ she said.

‘Next, I’ll email or ring the community pharmacy and follow up to make sure that the facts are changed appropriately.’

She also does home visits with clients and health workers to discuss any problems or questions they have to do with medicines.

As a diabetes educator, Ms van Rooijen sits in on patient sessions with the visiting specialist to ensure any medicine-related issues are followed up on.

If any topics arise that the staff feel unsure about, she puts together education sessions to get them up to speed.

‘If there’s something new that might be relevant to a particular area of the clinic, I’ll also casually draw attention to it with clients or health workers,’ she said.

‘For example, we have a smoking cessation program and I often talk with the girl that runs it about different approaches, such as addressing the new e-cigarette legislation with clients, or if a patient is on a lot of medicines, what the interactions are if they’re taking Champix.’

She also helped the clinic assess its standards and procedures through a recent medicine-related accreditation process.

‘We had a look at the procedures around the doctor’s bag, fridge monitoring and date checking – all the things which come second nature to pharmacists,’ Ms van Rooijen said.

A helping hand

Having a pharmacist on the team takes the pressure off the clinic’s GPs, who don’t always have the time or the knowledge to manage patients’ medicines.

A lot of the clients at the clinic have complex chronic health conditions and are on more than five medicines.

Diabetes is common, with resultant declining renal function, so Ms van Rooijen is often adjusting patients’ medicine doses to reflect that.

‘We had a look at the procedures around the doctor’s bag, fridge monitoring and date checking – all the things which come second nature to pharmacists.’

‘Then with diabetes comes cardiovascular risk,’ she said.

‘To ensure the medicines are optimised, you have to have a look at their cardiovascular function and the medicines they’re using to help that, and factor in which ones are the most appropriate for someone with diabetes and heart disease, as well as considering their renal function.’

It also helps to address any compliance issues, which often entails making little tweaks to help patients remember to take their medicines.

‘This could mean changing the doses for all their medicines to night time, so the patient only has to take them once a day,’ she said.

Empowering patients

In Ms van Rooijen’s experience, the best approach to patient consultations is carefully listening to what they have to say and using non-combative language.

‘That way, you’re more likely to have a good two-way flow of information and get an understanding of whether a patient is taking their medicine, what other things they are taking on top of it, and any other interactions that might be going on that we’re not aware of,’ she said.

She cited a recent example of a patient with chronic obstructive airway disease, who was having increasing pain issues and was concerned about the amount of relievers she was taking.

After a treatment plan was chosen in consultation with Ms van Rooijen and the patient’s doctors, the patient disclosed in a follow up visit that it wasn’t working.

‘We sat down around the table with her medicine list and talked about how pain adjuvants sometimes take a little while to work, which means we have to take the dose up really slowly,’ Ms van Rooijen said.

‘The patient said, “I’m so glad you said that, I was about ready to give up”… [But now] she said she was going to continue on with it and see what happens.’

PSA launches Reconciliation Action Plan

Meanwhile, PSA announced the launch of its Reconciliation Action Plan (RAP) framework last Friday, after receiving formal endorsement from Reconciliation Australia.

‘PSA’s RAP will build on current reconciliation initiatives within the organisation, driving reconciliation through awareness and action,’ National President Associate Professor Chris Freeman said.

‘[It] provides a strategic framework that will ensure PSA is a culturally safe workplace and welcoming for everyone, irrespective of their cultural heritage.’

PSA NT/SA State Manager Helen Stone, who was a key driver of the project, said providing culturally safe healthcare entails an understanding of the impact that generational disadvantage continues to have on the health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

‘The development of this RAP is a commitment to ensure the cultural literacy of PSA staff towards being a culturally safe workplace which is then reflected in our member education and practice support services,’ Ms Stone said.

John Jones MPS, pharmacist immuniser and owner of My Community Pharmacy Shortland in Newcastle, NSW[/caption]

John Jones MPS, pharmacist immuniser and owner of My Community Pharmacy Shortland in Newcastle, NSW[/caption]

Debbie Rigby FPS explaining how to correctly use different inhaler devices[/caption]

Debbie Rigby FPS explaining how to correctly use different inhaler devices[/caption]

Professor Sepehr Shakib[/caption]

Professor Sepehr Shakib[/caption]

Lee McLennan MPS[/caption]

Lee McLennan MPS[/caption]

Dr Natalie Soulsby FPS, Adv Prac Pharm[/caption]

Dr Natalie Soulsby FPS, Adv Prac Pharm[/caption]

Joanne Gross MPS[/caption]

Joanne Gross MPS[/caption]