More than 1.3 million Australians in rural and remote areas do not take their medicines at all or as intended, according to a new report from PSA.

The Medicine safety: rural and remote care report, developed for PSA by Charles Sturt University, was launched by New South Wales Minister for Health Brad Hazzard on Saturday (13 March).

The Medicine safety: rural and remote care report, developed for PSA by Charles Sturt University, was launched by New South Wales Minister for Health Brad Hazzard on Saturday (13 March).

Of the 7 million Australians living in rural and remote areas, each year 72,500 Australians are admitted to hospital for medicine-related problems, costing the health care system $400 million. At least half of this harm is preventable.

Launching the report, Minister Hazzard thanked pharmacists for rising to the challenge of caring for their communities in the face of bushfires, drought and the COVID-19 pandemic.

‘The further out you get from major cities … the challenge of providing healthcare at every level becomes more problematic,’ he said.

‘No matter where you are, pharmacists are a very, very important part of the health system.

‘Not just the pharmaceutical and technical, medicinal support, but also psychological support.’

Thanks to the Pharmaceutical Society of Australia for inviting me to attend their annual conference & to launch the Medicine Safety: Rural and Remote Care report highlighting the challenges for more than 7 million Australians living in rural/remote areas. @NSWHealth pic.twitter.com/97uhAo1aIM

— Brad Hazzard (@BradHazzard) March 13, 2021

Minister Hazzard said the new report, which follows PSA’s previous publications, Medicine safety: take care and Medicine safety: aged care, would be ‘extremely valuable for all governments – states, territories and federal’. He promised to raise the issues with his parliamentary colleagues.

Rural challenges

PSA National President Associate Professor Chris Freeman said the report revealed significant health discrepancies for those living in rural and remote Australia compared to those in metropolitan areas.

‘The seven million Australians living in rural and remote Australia deserve better,’ A/Prof Freeman said.

‘[The problems are] in part due to the tyranny of distance, inflexible regulations and health workforce shortages.

‘Whether you live in Bronte or Broken Hill, Perth or Port Augusta, Manly or Moree – you should be protected from avoidable harm which medicines can cause.’

Other key findings include:

- the rate of unintentional drug-induced deaths is higher than in capital cities

- potentially preventable hospitalisations are up to 2.4 times more than that of non-rural Australians

- the rates of medicines supplied for mental health conditions are lower in remote and very remote areas, despite the higher incidence of mental health issues in these locations

- the rate of preventable hospitalisations for Indigenous Australians is three times higher than that of non-Indigenous Australians

A/Prof Freeman said the report also revealed a lack of information about the health care needs of rural and remote Australians.

‘One of the most concerning findings is the lack of data. These numbers are conservative and a gross underestimation,’ he said.

‘We need to be far better at recording these medicine-related problems when they occur so we can provide better care and better solutions.’

We can do better! #Pharmacists make a difference in #ruralmedicinesafety @PSA_National pic.twitter.com/6xWmIciyLg

— Anna Barwick MPS (@IndispensablePh) March 12, 2021

Building the workforce

The report recommends a series of actions to help address medicine-related harm in rural and remote Australia. This includes building the rural and remote pharmacist workforce capacity and capability.

If things continue as normal, it is estimated there will be as few as 52 pharmacists per 100,000 people in regional and remote areas by 2027, compared to 113 pharmacists per 100,000 people in major cities.

The PSA recommends establishing accredited rural generalist pharmacists, who would work with GPs and other health professionals to prescribe, order pathology tests and do more to support people’s chronic diseases.

It is also vital to establish a workforce strategy and provide funding to attract and retain pharmacists in rural and remote Australia in primary care settings such as community pharmacy, general practice, aged care facilities and Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Centres, as well as rural and regional hospitals.

At the report launch, pharmacist and federal shadow assistant minister for mental health and carers Emma McBride MPS, said growing the pharmacist workforce in remote and rural areas was ‘critical’.

‘We all know … that the further you are from a big city, the less access you have to healthcare, which means the disease burden is greater,’ she said.

‘If we can see a proper coordinated workforce strategy at the federal level, working with the jurisdictions, that’s where we’ll be able to see a real change in access to healthcare.’

Ms McBride also thanked ‘each and every pharmacist’ for their work, and said the pandemic highlighted the ways the profession contributes.

‘As a pharmacist myself, I’ve been so proud to be part of our profession and see pharmacists working at the top of their scope and to their full range of practice,’ she said.

‘From this crisis there’s a really big opportunity for pharmacists to be recognised, and the next thing is to properly value them through remuneration.’

Rural recommendations

The report also calls on governments to fund pharmacists to work in Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations and fund case conferencing for pharmacists as part of the healthcare team in rural and remote areas.

We need more pharmacists in Aboriginal Health Services supporting our nation’s first people to #closethegap @NACCHOAustralia @coalition_peaks @PharmGuildAus #medicinesafety #ruralmedicinesafety #PSA21ATU https://t.co/cS2LRjZs9d

— Close the Gap 🖤 💛 ❤️ Campaign 💙 💚 (@closethegapOZ) March 13, 2021

‘Pharmacists in rural and remote areas are often the main available health care provider and we need to allow them to be able to use their expertise to support the patients,’ A/Prof Freeman said.

‘It should not matter where you live – all Australians are worthy of the best health care the country can provide. We must address rural and remote challenges of medicine safety as a matter of urgency.’

Read PSA’s Medicine safety: rural and remote care report here.

‘We’re increasingly seeing incidents where alert fatigue has been identified as a contributing factor. It’s not that there wasn’t an alert in place, but that it was lost among the other alerts the clinician saw,’ Prof Baysari says.

‘We’re increasingly seeing incidents where alert fatigue has been identified as a contributing factor. It’s not that there wasn’t an alert in place, but that it was lost among the other alerts the clinician saw,’ Prof Baysari says.

Beyond the arrhythmia, AF often signals broader pathological processes that impair cardiac function and reduce quality of life and life expectancy.5 Many of these conditions are closely linked to social determinants of health, disproportionately affecting populations with socioeconomic disadvantage. Effective AF management requires addressing both the arrhythmia and its underlying contributors.4

Beyond the arrhythmia, AF often signals broader pathological processes that impair cardiac function and reduce quality of life and life expectancy.5 Many of these conditions are closely linked to social determinants of health, disproportionately affecting populations with socioeconomic disadvantage. Effective AF management requires addressing both the arrhythmia and its underlying contributors.4  C – Comorbidity and risk factor management

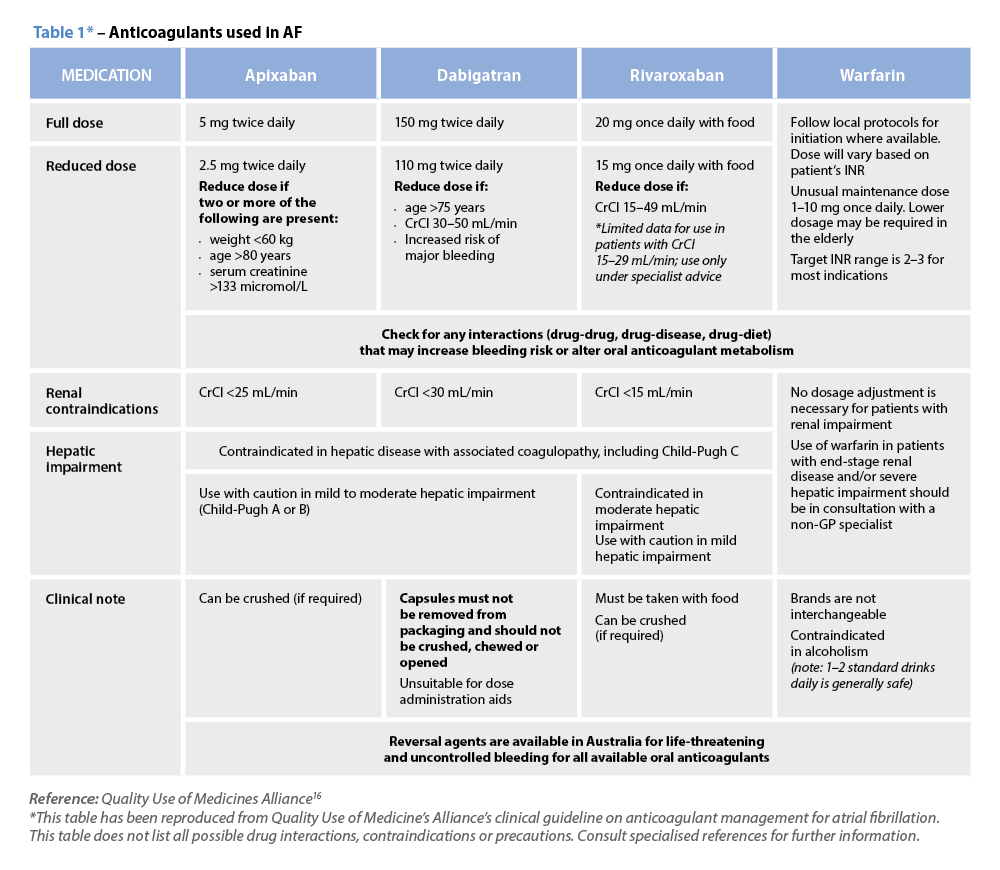

C – Comorbidity and risk factor management Warfarin

Warfarin