While health and fitness apps promise to improve the quality of life for users through positive behavioural changes, few systematic reviews have collated their efficacy via randomised control trials.

A study published by Bond University indicates some of these apps may have no effect or even a negative effect on a user’s health, when compared to control groups.

Even then, the quality of evidence in the research was poor.

‘The overall low quality of the evidence of effectiveness greatly limits the prescribability of health apps,’ the npj Digital Medicine paper stated.

‘Without adequate evidence to back it up, digital medicine and app “prescribability” might stall in its infancy for some time to come.’

After searching global databases, the researchers found only 23 randomised control trials (RCTs) of 22 currently available stand-alone health apps robust enough for inclusion in their study. Some of these apps provided intervention of: treatment adherence and telemedicine support for Type 1 diabetes; education and rescue therapy for mild to moderate anxiety; cognitive behavioural therapy for depression, and weight loss in conjunction with counselling for patients with BMI exceeding 25 kg/m2.

Of those, the evidence showed that just eleven apps were prescribable, or potentially prescribable.

One Swedish government app designed to reduce alcohol use among university students actually led to them drinking more.

The lead author of the study, Dr Oyungerel Byambasuren, told Australian Pharmacist that if patients wanted to use health apps there were three things pharmacists should do.

‘Direct them to a reputable source like the NHS App library and HANDI, and always advise to exercise common sense and precautions in regards to the privacy and data safety,’ she said.

‘Advise them to use the apps they choose persistently over a substantial amount of time and with health professionals’ support and guidance to see real benefit.

‘Remind them that health apps are not a substitute for professional medical advice or care.’

Dr Byambasuren added that persistence and accountability seemed to matter in digital therapeutics.

‘Research also showed that people’s app use drops to zero in a very short amount of time especially when they are not followed up by healthcare professionals,’ she said.

Despite the findings, Dr Byambasuren said health apps had great potential.

‘We have no doubt that health apps will be integral part of non-pharmacological intervention toolbox of GPs and pharmacists,’ she said.

‘We need to encourage health apps to be tested before they’re released to the market and the testing to be of rigorous standard.

‘When studies show positive results, they need to be replicated and validated for apps to be fully prescribable.’

Further details of the study can be read here.

‘We’re increasingly seeing incidents where alert fatigue has been identified as a contributing factor. It’s not that there wasn’t an alert in place, but that it was lost among the other alerts the clinician saw,’ Prof Baysari says.

‘We’re increasingly seeing incidents where alert fatigue has been identified as a contributing factor. It’s not that there wasn’t an alert in place, but that it was lost among the other alerts the clinician saw,’ Prof Baysari says.

Beyond the arrhythmia, AF often signals broader pathological processes that impair cardiac function and reduce quality of life and life expectancy.5 Many of these conditions are closely linked to social determinants of health, disproportionately affecting populations with socioeconomic disadvantage. Effective AF management requires addressing both the arrhythmia and its underlying contributors.4

Beyond the arrhythmia, AF often signals broader pathological processes that impair cardiac function and reduce quality of life and life expectancy.5 Many of these conditions are closely linked to social determinants of health, disproportionately affecting populations with socioeconomic disadvantage. Effective AF management requires addressing both the arrhythmia and its underlying contributors.4  C – Comorbidity and risk factor management

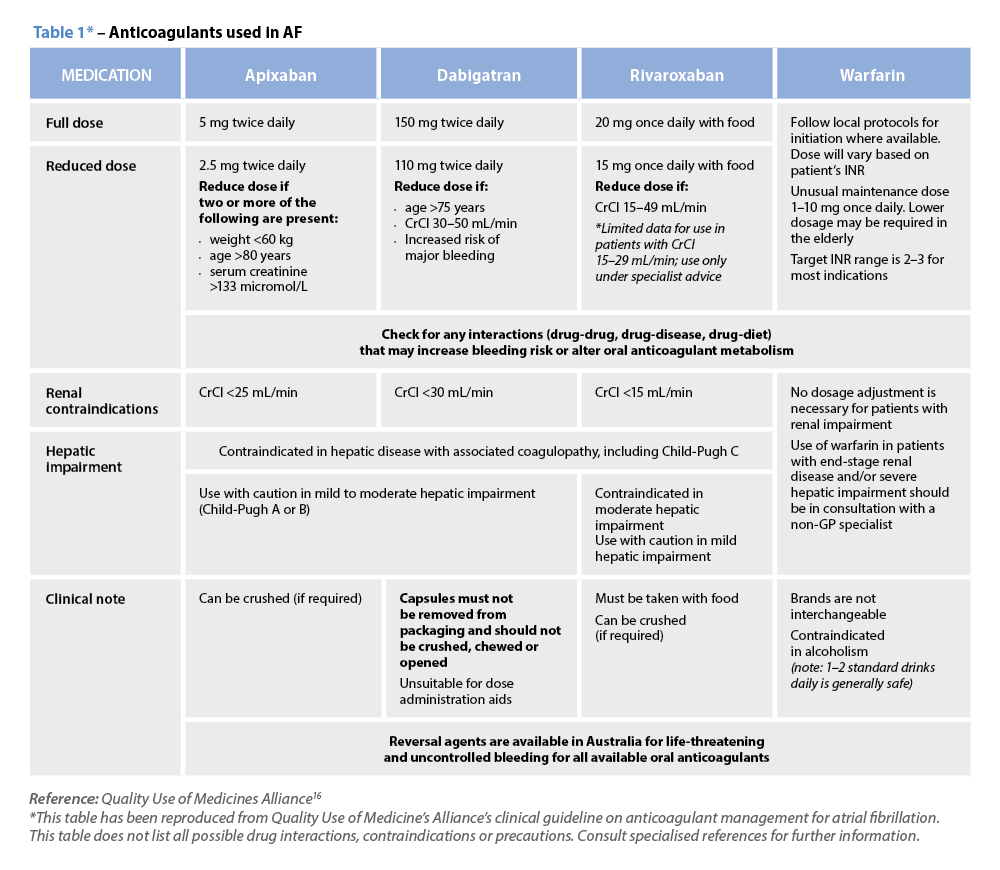

C – Comorbidity and risk factor management Warfarin

Warfarin