td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 29352

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-05-14 15:03:20

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-05-14 05:03:20

[post_content] => Dedicated palliative care training for pharmacists is not commonplace. This PSA-developed course aims to change that.

It can be difficult to tell from a prescription that a patient is receiving palliative care, said Tanya Maloney MPS, a community pharmacist in Coffs Harbour, NSW.

[caption id="attachment_29354" align="alignright" width="233"] Tanya Maloney MPS[/caption]

‘What we lack in pharmacy is training on how to approach those difficult conversations in the right way so we can ask them a few questions to determine that,’ she said. ‘We're often a bit nervous about saying the wrong thing.’

Though passionate about palliative care, Ms Maloney and her team have had to learn on the job.

‘We haven’t had any extra training and want to know how we can contribute more.’

This is a common issue through the profession, with a lack in palliative care education tailored specifically to pharmacists, leading to a knowledge gap, said PSA Senior Pharmacist (Consulting and Program Delivery) Megan Tremlett MPS – who has managed a number of palliative care projects through Primary Health Networks and at a state level in recent years.

‘As pharmacists, we don't learn a lot about palliative care in our undergraduate course. And the majority of pharmacists haven't done any extra palliative care education since their university days.’

To address this, PSA launched the ASPIRE Palliative Care Foundation Training Program on 13 May. The free, CPD-accredited course – supported by Palliative Care Australia and funded under the National Palliative Care Grants Program – upskills pharmacists regardless of practice setting.

‘The training program has been created with extensive stakeholder consultation to provide pharmacists with a thorough introduction to palliative care across the eight modules’ Ms Tremlett said.

Rather than training pharmacists to specialise in palliative care, the training program is intended to lift the baseline knowledge of the profession, said Leah Robinson, Project Manager at PSA, who worked on the development of the program with Ms Tremlett.

‘It’s about understanding the different settings and phases of palliative care and at which points pharmacists can provide practical support to help families, patients and healthcare professionals in supporting palliative care.’

A foundational understanding of palliative and end-of-life care across the health workforce is essential to meeting community needs, said Camilla Rowland, CEO of Palliative Care Australia.

‘Supporting people to live, and die well, means building palliative care capability across the entire health system. That includes pharmacists, often among the first healthcare professional patients and carers turn to for advice.’

Tanya Maloney MPS[/caption]

‘What we lack in pharmacy is training on how to approach those difficult conversations in the right way so we can ask them a few questions to determine that,’ she said. ‘We're often a bit nervous about saying the wrong thing.’

Though passionate about palliative care, Ms Maloney and her team have had to learn on the job.

‘We haven’t had any extra training and want to know how we can contribute more.’

This is a common issue through the profession, with a lack in palliative care education tailored specifically to pharmacists, leading to a knowledge gap, said PSA Senior Pharmacist (Consulting and Program Delivery) Megan Tremlett MPS – who has managed a number of palliative care projects through Primary Health Networks and at a state level in recent years.

‘As pharmacists, we don't learn a lot about palliative care in our undergraduate course. And the majority of pharmacists haven't done any extra palliative care education since their university days.’

To address this, PSA launched the ASPIRE Palliative Care Foundation Training Program on 13 May. The free, CPD-accredited course – supported by Palliative Care Australia and funded under the National Palliative Care Grants Program – upskills pharmacists regardless of practice setting.

‘The training program has been created with extensive stakeholder consultation to provide pharmacists with a thorough introduction to palliative care across the eight modules’ Ms Tremlett said.

Rather than training pharmacists to specialise in palliative care, the training program is intended to lift the baseline knowledge of the profession, said Leah Robinson, Project Manager at PSA, who worked on the development of the program with Ms Tremlett.

‘It’s about understanding the different settings and phases of palliative care and at which points pharmacists can provide practical support to help families, patients and healthcare professionals in supporting palliative care.’

A foundational understanding of palliative and end-of-life care across the health workforce is essential to meeting community needs, said Camilla Rowland, CEO of Palliative Care Australia.

‘Supporting people to live, and die well, means building palliative care capability across the entire health system. That includes pharmacists, often among the first healthcare professional patients and carers turn to for advice.’

Learning about symptom management

The ASPIRE training program has a module dedicated to symptoms and the trajectory of people living with life-limiting illness.

Under a subsequent symptom management module, pharmacists can access resources and references for pharmacological management of the symptoms associated with dying that covers:

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 29045

[post_author] => 10221

[post_date] => 2025-05-13 16:45:40

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-05-13 06:45:40

[post_content] => Case scenario

Amra, 80 years old and a regular patient of yours, has been discharged from hospital after an admission for a fall. She presents at the pharmacy with a bag of medicines and hands you a discharge medicines list. She appears to have been initiated on some new medicines in hospital and expresses confusion on which of her pre-hospital medicines to continue. You view her dispense history and My Health Record and notice discrepancies. It is unclear to you or Amra why some medicines have been initiated. She has an appointment with her GP in a couple of days.

Learning objectivesAfter reading this article, pharmacists should be able to:

|

The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC) defines transitions of care as the period when all or part of a person’s healthcare is transferred between care providers or care settings.1

Transitions of care are periods of high risk for medication errors and miscommunication, leading to patient harm. When medicines safety is not prioritised at transitions of care, the risk of adverse events is increased, such as readmission to hospital and adverse drug reactions. A Cochrane review found that more than 50% of patients experience a medication error during transitions of care.2 A systematic review found that following hospital discharge to the community, 53% of adult patients experience at least one medication error, 50% experience one or more unintentional medication discrepancies (a subset of medication errors), and 19% experience one or more adverse drug events.3 A systematic review and meta-analysis found the prevalence of medication-related readmissions and adverse drug reaction-related readmissions in older people were 9% and 6%, respectively, with about one-fifth of these preventable.4

Preventing medication-related harm at transitions of care is a key priority in the World Health Organization’s (WHO) third Global Patient Safety Challenge (Medication Without Harm).5 The ACSQHC’s response to the Challenge, published in 2020, described prioritising medication reconciliation at all transitions of care to reduce the risk of medication errors.6 Its response also recommended the use of My Health Record to engage patients and carers in curation and communication of medication regimen information.

The ACSQHC’s response focused on transitions from hospital, a period known to be particularly high risk, and also recommended standardising the presentation of discharge summaries.6 For people with complex care needs, initiatives to reduce preventable medication-related readmissions were encouraged, such as early post-discharge medication reviews (hospital outreach or primary care led), and cross-sector case conferencing.6 Refinement of risk criteria or indicators was recommended to direct interventions towards patients at the greatest risk of medication-related harm.6

The ACSQHC’s response did not specifically address other known contributors to medication-related harm during transitions of care, such as ensuring timely access to medicines and the tools that are sometimes required to use them, such as interim medication administration charts when discharged to residential care, dose administration aids, and adequate quantities of medicines supply.7,8

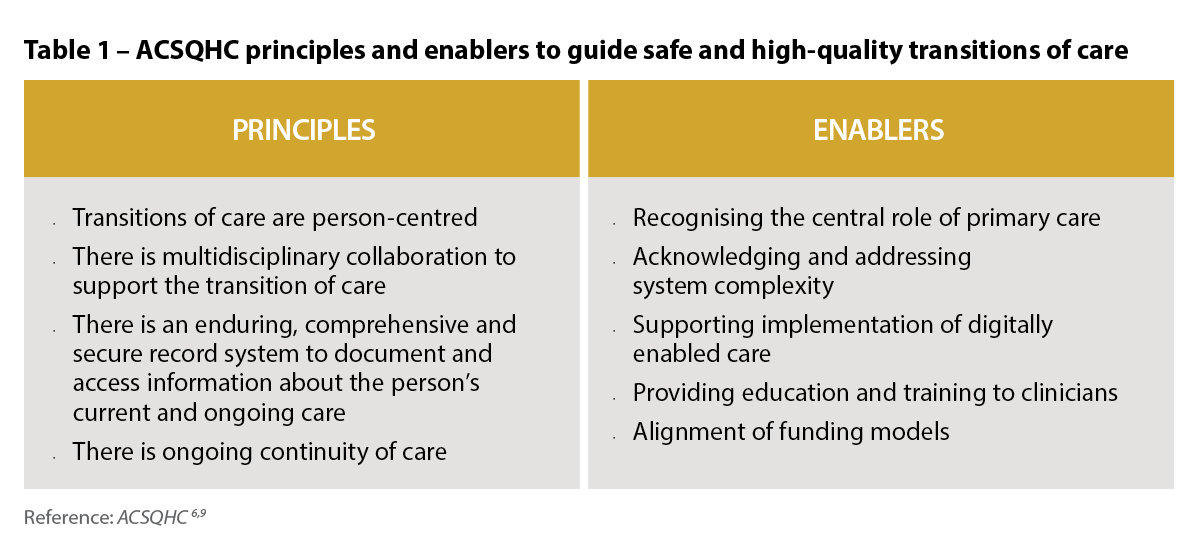

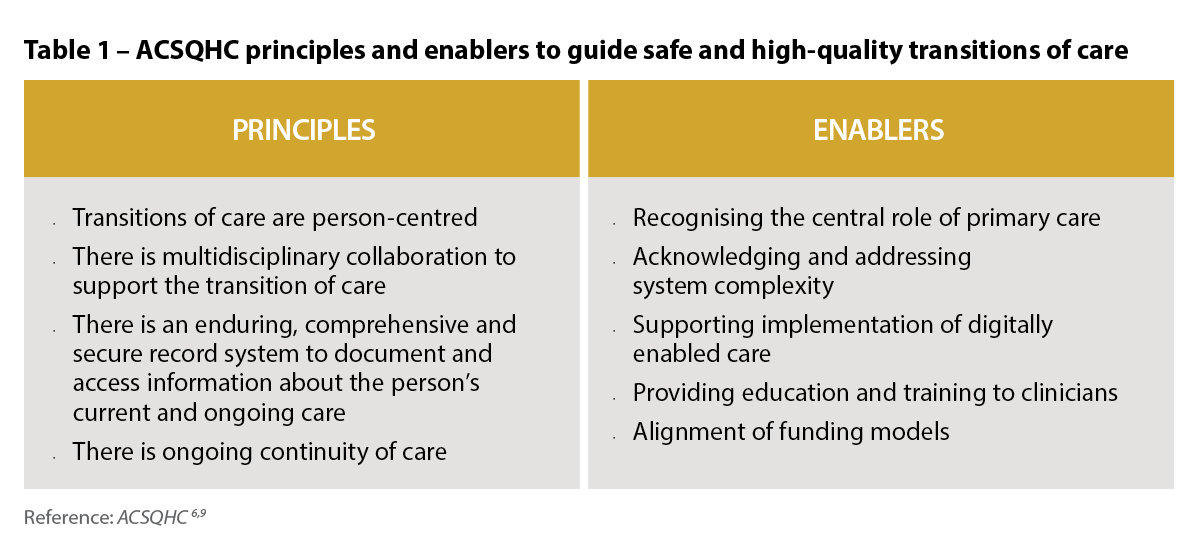

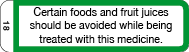

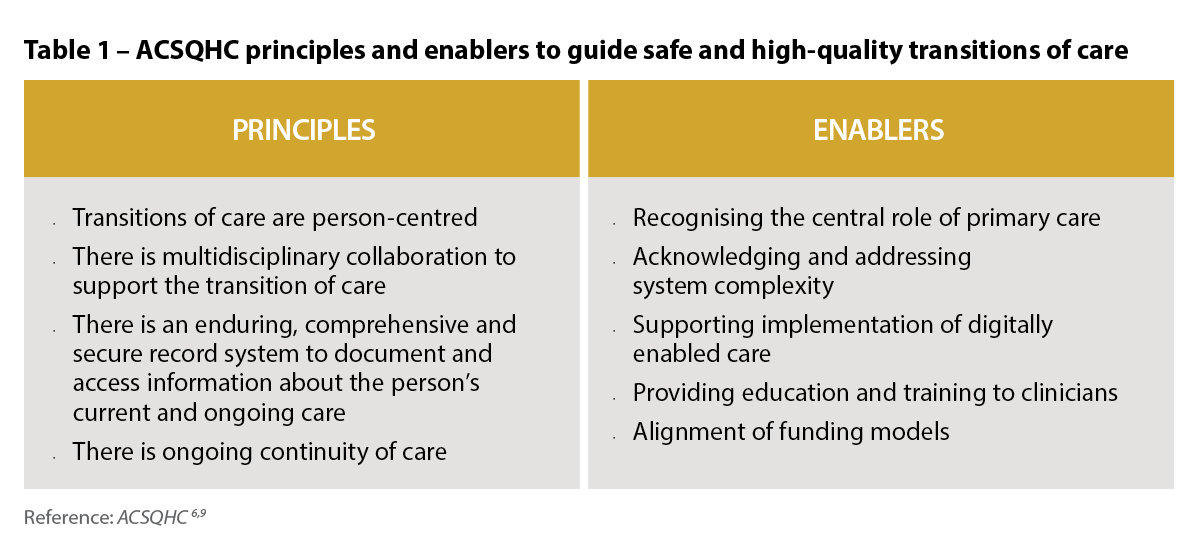

The ACSQHC has recently published a set of principles to guide safe and high-quality transitions of care that highlight the need for multidisciplinary collaboration and coordination that relies on shared responsibility and accountability.9 The consistent application of these principles within practice, standards, policy and guidance are fundamental for safe transitions of care and apply to transitions of care wherever healthcare is received including primary, community, acute, subacute, aged and disability care.9

The principles and their enablers are shown in Table 1.

Australia’s priority actions to address medicines safety at transitions of care

Australia’s priority actions to address medicines safety at transitions of careProgress toward Australia’s priority actions to address medicines safety at transitions of care has been mixed.10 Embedding medication reconciliation at admission and discharge from hospital has advanced and is now part of medicines safety standards that hospitals need to meet for accreditation.

My Health Record has improved access to patients’ medication histories; however, patient engagement remains low, and, like all medication records, verification of data with the patient and other sources is required.11,12 Implementation of the Pharmacist Shared Medicines List (a verified medication history that can be uploaded to My Health Record) has been limited. Discharge summaries continue to have deficiencies, including inaccurate medicine lists and inadequate explanations of medicine changes.13 Primary care medicine lists and dose administration aid medicine labels, which are often used by hospital doctors to chart medicines on admission, are also frequently inaccurate.14,15

Australian research highlights concerns about lack of awareness and uptake of post-discharge Home Medicines Reviews (HMRs) and Residential Medication Management Reviews (RMMRs) and the complexity in facilitating timely post-discharge medication reviews.16,17 Hospital outreach pharmacist medication review services and cross-sector multidisciplinary case conferencing are uncommon. There has been progress in developing validated criteria to identify patients at risk of medication-related readmission,18 though more work is needed to ensure generalisability and implementation.10

Progress towards ensuring timely access to medicines following hospital discharge has been mixed.10 Reforms to enable medicines to be supplied by hospitals using the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, and implementation of interim medication administration charts for patients discharged to residential care, have not occurred in all jurisdictions.

In 2020, after decades of advocacy, Commonwealth-funded medication review program rules changed to allow hospital-based medical specialists to refer patients to credentialed pharmacists for collaborative post-discharge medication management reviews. In response, the Society of Hospital Pharmacists (now known as Advanced Pharmacy Australia [AdPha]) published a Hospital Pharmacy Practice Update, Hospital-Initiated Medication Reviews, which detailed information about pathways for patients to have post-discharge HMRs, RMMRs and Hospital Outreach Medication Reviews, as well as flagging MedsChecks as a medication reconciliation pathway.19 Unfortunately, resources were not provided by the Commonwealth or state health departments for promotion, training or implementation support for hospitals to implement hospital-initiated medication reviews, and uptake of these pathways has been low.

An article published in 2022 presented barriers and enablers to hospital-initiated medication reviews, and highlighted the need for a stewardship approach to promote safe and high-quality medication management at transitions of care, with a key focus on facilitating early post-discharge medication reviews (within 10 days).20 The authors have continued to advocate for a hospital-led stewardship approach to address the perennial problem of medicines safety at transitions of care.10,21

The recently published AdPha Standard of Practice for Pharmacy Services Specialising in Transitions of Care describes current best practice for the provision of pharmacy services that specialise in transitions of care, such as hospital outreach pharmacists and community liaison pharmacists, and supports the introduction of transitions of care stewardship programs into existing organisational clinical systems.22

The recently published AdPha Standard of Practice for Pharmacy Services Specialising in Transitions of Care describes current best practice for the provision of pharmacy services that specialise in transitions of care, such as hospital outreach pharmacists and community liaison pharmacists, and supports the introduction of transitions of care stewardship programs into existing organisational clinical systems.22

Stewardship in the context of health care refers to a structured program of strategies and interventions that address challenges within a specific clinical area, and ensure appropriate and efficient use of resources. Medicines stewardship programs focus on improving medicines use in areas where there is a high risk of inappropriate prescribing or adverse outcomes. Examples of successful programs include: antimicrobial, opioid analgesic, anticoagulation and psychotropic stewardship.21

Medicines stewardship programs aim to improve medication management at individual and population levels to ensure consistent, appropriate care. At a population level, this may include developing guidelines and providing standardised processes and templates. At an individual level, it includes delivering tailored person-centred interventions to optimise medication outcomes.

Common elements of successful medicines stewardship programs include multidisciplinary leadership, stakeholder engagement, tailored communication strategies, behavioural changes, implementation science methodologies, and ongoing program monitoring, evaluation and reporting.21 Stewardship programs are often led or administered by a dedicated stewardship officer (usually a pharmacist) or team.21

Applying a stewardship approach to transitions of care may provide opportunities to focus organisational resources, foster multi- or interdisciplinary collaboration, and improve coordinated care when individuals transfer between care providers or settings.

In 2023, the ACSQHC commissioned a rapid literature review and environmental scan examining Australian and international medication management strategies, including stewardship programs, at transitions of care focusing on admission to hospital and discharge to the community or residential care.23,24

The literature review identified that, globally, there are no published studies or existing frameworks that describe a stewardship program specifically addressing medication management at transitions of care.24

Given the evidence from the literature review and environmental scan, the ACSQHC set about developing a Medication Management at Transitions of Care Stewardship Framework (the Framework). The Framework is scheduled for release in the second quarter of 2025.

The Framework is intended to provide healthcare organisations (hospitals) with a systematic approach for implementing coordinated medication management activities and interventions to optimise safe and high-quality transitions of care, with a focus on patients admitted to hospital and discharged to the community or residential aged care. The Framework will provide guidance that can be adapted to local context and the circumstances of individuals transitioning across care settings.

The Framework will be supported by existing national standards and guidelines, including:

The ACSQHC’s principles of safe and high-quality transitions of care9 should also be considered in the local implementation of a medication management at transitions of care stewardship program.

Leveraging digital health

Digital health is a key enabler to achieve interoperable, accurate and timely communication between clinicians in the acute and primary care settings. The Framework will align with the National Digital Health Strategy 2023–202827 and the Strategy Delivery Roadmap.28

Health facilities are encouraged to embed digitally enabled care to strengthen effective interdisciplinary communication and improve safe and high-quality medication management at transitions of care.29

The Framework is designed with a hospital focus, and it is intended that it will be used by hospitals to guide stewardship and coordination in collaboration with primary care practitioners.29

General practice coordination of ongoing medical care prior to and following hospital discharge is vital, as is community pharmacist coordination of medication supply and management. Pharmacists embedded in general practice, onsite aged care pharmacists, and credentialed pharmacists providing HMRs and RMMRs, can also play an important role. However, it is not possible for general practice and primary care pharmacists to coordinate all time-critical aspects of medication management for complex hospital discharges that occur 7 days a week, and sometimes outside of business hours. In the first instance, hospitals need to take responsibility for bridging the gap by29:

The authors encourage all pharmacists to engage with the Framework. It is a world-first document that will drive system improvements so Australians receive high-quality care, and is a pivotal response to the WHO’s third Global Patient Safety Challenge (Medication Without Harm) priority, transitions of care.

Case scenario continuedYou phone the discharging hospital pharmacist (whose name was recorded on the patient’s discharge medicines list) to clarify Amra’s medicine changes and discharge medication management plan. You speak with Amra about your discussion and obtain consent to complete a MedsCheck and chat with her GP about any changes post-discharge. You go through each of her medicines and prepare her an updated medicines list. You also discuss the potential benefits of a Home Medicines Review (HMR) when there has been a hospital admission and medicine changes. You ask if she wishes for you to discuss an HMR referral with her GP which could be actioned at her upcoming GP appointment. She indicates an HMR would be welcome and thanks you for helping her. |

Manya Angley (she/her) BPharm, PhD, FPS, CredPharm (MMR), FAdPha is an Advanced Practice Pharmacist experienced in general practice, disability and aged care.

Debbie Rigby (she/her) BPharm, GradDipClinPharm, FASCP, FPS, FACP, FAICD, FSHP, FANZCAP (GeriMed, Resp) is an Advanced Practice Pharmacist qualified in clinical pharmacy, geriatrics and respiratory medicine.

Rohan Elliott (he/him) BPharm, BPharmSc(Hons), MClinPharm, PhD, FAdPhA, FANZCAP (GeriMed, Research) is an Advanced Practice Pharmacist with experience in hospitals, aged care and transitions of care.

Elizabeth Manias (she/her) RN, BPharm, MPharm, MNStud, PhD, FANZCAP (Transitions of care, Geriatric Medicine)

Manya Angley, Debbie Rigby and Rohan Elliott are co-investigators on a Medical Research Future Fund (MRFF) 2022 transitions of care project. MRFF is funded by the Australian Government. They are also co-authors of a literature review of transitions of care stewardship that was funded by the ACSQHC.

Elizabeth Manias is a member of the Transitions of Care and Primary Care Leadership Committee of Advanced Pharmacy Australia.

[post_title] => Improving medicines safety at transitions of care [post_excerpt] => Transitions of care are periods of high risk for medication errors and miscommunication, leading to patient harm. [post_status] => publish [comment_status] => open [ping_status] => open [post_password] => [post_name] => improving-medicines-safety-at-transitions-of-care [to_ping] => [pinged] => [post_modified] => 2025-05-14 13:04:04 [post_modified_gmt] => 2025-05-14 03:04:04 [post_content_filtered] => [post_parent] => 0 [guid] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/?p=29045 [menu_order] => 0 [post_type] => post [post_mime_type] => [comment_count] => 0 [filter] => raw ) [title_attribute] => Improving medicines safety at transitions of care [title] => Improving medicines safety at transitions of care [href] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/improving-medicines-safety-at-transitions-of-care/ [module_atts:td_module:private] => Array ( ) [td_review:protected] => Array ( [td_post_template] => single_template_4 ) [is_review:protected] => [post_thumb_id:protected] => 29343 [authorType] => )td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 29331

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-05-12 13:28:53

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-05-12 03:28:53

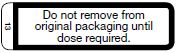

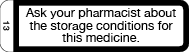

[post_content] => Both Cautionary Advisory Label (CAL) 6 and CAL 13 have been overhauled to sharpen storage advice.

CAL 6 explanatory notes advice in Digital Australian Pharmaceutical Formulary and Handbook (APF) now mentions considerations for room-temperature time windows for refrigerated medicines, while CAL 13’s tightened wording and advice flags truly sensitive formulations – ensuring pharmacists give patients clearer, more precise guidance.

What’s changing?

The familiar ‘Refrigerate, do not freeze’ warning of CAL 6 is not changing, however its explanatory notes have been expanded.

[caption id="attachment_29335" align="aligncenter" width="180"] CAL 6[/caption]

There are many instances whereby refrigeration of temperature sensitive medicines may not be practical, for example travel days, power outages or ‘in-use’ multi-dose containers/devices. The updated explanatory notes advise pharmacists that they should refer to the medicines approved product information (PI) and counsel their patients on how to best store these medicines – covering when their temperature sensitive medicines may safely remain at room temperature (below 25 °C) – if applicable.

[caption id="attachment_29336" align="aligncenter" width="176"]

CAL 6[/caption]

There are many instances whereby refrigeration of temperature sensitive medicines may not be practical, for example travel days, power outages or ‘in-use’ multi-dose containers/devices. The updated explanatory notes advise pharmacists that they should refer to the medicines approved product information (PI) and counsel their patients on how to best store these medicines – covering when their temperature sensitive medicines may safely remain at room temperature (below 25 °C) – if applicable.

[caption id="attachment_29336" align="aligncenter" width="176"] The old CAL 13[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_29337" align="aligncenter" width="189"]

The old CAL 13[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_29337" align="aligncenter" width="189"] The new CAL 13[/caption]

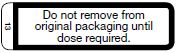

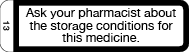

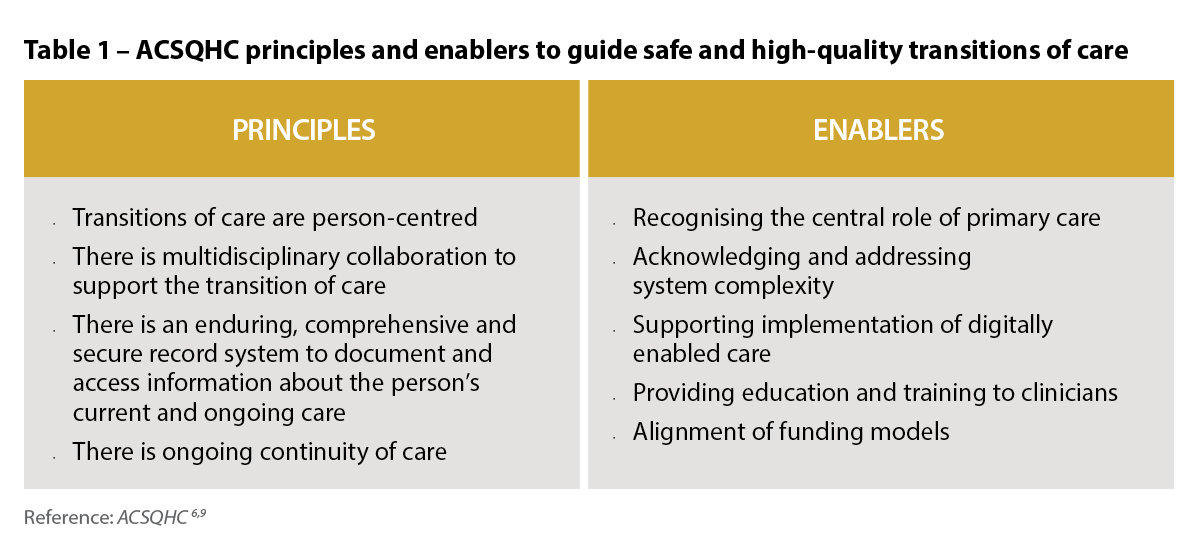

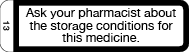

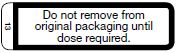

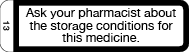

Meanwhile, CAL 13 has been reworded. Previously ‘Do not remove from original packaging until dose required’, the new prompt, ‘Ask your pharmacist about the storage conditions for this medicine,’ applies only to dosage forms and active ingredients truly sensitive to light, moisture or temperature excursions.

This includes orally disintegrating tablets, effervescents, sublingual or buccal lozenges, dispersible granules, wafers and chewables, as well as amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, dabigatran, glyceryl trinitrate, nicorandil, nifedipine, phenothiazines, tamoxifen and sodium valproate.

CAL 13 may also be applied in addition to other CALs relating to storage requirements (e.g. CALs 6, 7a or 7b) when complex storage instructions are applicable, and these other CALs do not adequately cover these.

To support the change to CAL 13, the APF’s Good dispensing practice chapter has been updated with clearer and expanded guidance on providing advice to patients on how to store medicines, including that:

The new CAL 13[/caption]

Meanwhile, CAL 13 has been reworded. Previously ‘Do not remove from original packaging until dose required’, the new prompt, ‘Ask your pharmacist about the storage conditions for this medicine,’ applies only to dosage forms and active ingredients truly sensitive to light, moisture or temperature excursions.

This includes orally disintegrating tablets, effervescents, sublingual or buccal lozenges, dispersible granules, wafers and chewables, as well as amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, dabigatran, glyceryl trinitrate, nicorandil, nifedipine, phenothiazines, tamoxifen and sodium valproate.

CAL 13 may also be applied in addition to other CALs relating to storage requirements (e.g. CALs 6, 7a or 7b) when complex storage instructions are applicable, and these other CALs do not adequately cover these.

To support the change to CAL 13, the APF’s Good dispensing practice chapter has been updated with clearer and expanded guidance on providing advice to patients on how to store medicines, including that:

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 29310

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-05-07 14:26:37

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-05-07 04:26:37

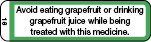

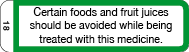

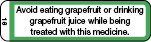

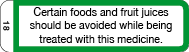

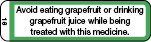

[post_content] => Merging CAL 18 and CAL I removes duplication and confusion, helping patients receive clearer, more actionable dietary advice.

Australian Pharmacist explores what pharmacists and patients need to know.

What’s changing?

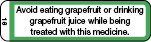

Cautionary advisory label (CAL) 18 and CAL I currently provide dietary advice for specific medicines:

[caption id="attachment_29312" align="aligncenter" width="151"] CAL 18[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_29311" align="aligncenter" width="152"]

CAL 18[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_29311" align="aligncenter" width="152"] CAL I[/caption]

CAL I[/caption]

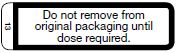

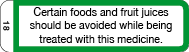

Instead of having two labels that relate to avoiding certain foods and juices (CAL 18 and CAL I), there will now be one – an updated CAL 18.

[caption id="attachment_29313" align="aligncenter" width="189"] Revised CAL 18[/caption]

Revised CAL 18[/caption]

What’s the rationale?

Currently, CAL 18 only warns about grapefruit due to its effect on the bioavailability of certain medicines through the selective inhibition of cytochrome P450 3A4 isoenzymes. But the product information (PI) for new medicines that are substrates for CYP3A4 increasingly mention other fruits (beyond just grapefruit) as interacting with medicines via inhibition of CYP3A4. This includes seville oranges, pomelo, star fruit, bitter melon and pomegranate.

As it stands, the wording of CAL 18 is not broad enough to cover these scenarios.

CAL I is currently used to advise patients about fruits and juices that interact with medicines through mechanisms other than inhibition of CYP3A4.

For example, food and drink interactions with non-selective monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and interactions between medicines and fruit juices through mechanisms other than CYP3A4 inhibition (e.g. fexofenadine, which has been found to interact with orange and apple juice).

However, there have been reports of confusion associated with ‘I’ appearing very similar to ‘1’ in the CAL recommendation table. There are also not many medicines CAL I is relevant to at present, so it therefore has limited applicability.

The revised CAL 18, now reading ‘Certain foods and fruit juices should be avoided while being treated with this medicine’, will now cover:

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 29295

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-05-05 14:47:58

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-05-05 04:47:58

[post_content] => With measles cases climbing across Australia and pharmacies increasingly listed as exposure sites, community pharmacists must be prepared.

Earlier this year, a patient who had just returned from Vietnam walked into Advantage Chesterville Pharmacy in Melbourne with a script for antibiotics.

‘She was wearing a face mask, and when I spoke to her she just said that she had a cough but she wasn't sure what the cough was from,’ said community pharmacist Minh Ngo MPS, who was on duty when the patient came through.

Some time later, the pharmacy received word that the patient was infected with measles.

‘She either informed the hospital or the GP, but we just got a call from the [Victorian] Department of Health to notify us that we were an exposure case,’ she said.

With measles spreading around Australia at an unprecedented rate, this is a position many pharmacists may soon find themselves in.

Victoria is in the midst of its worst measles outbreak in a decade, with 25 cases recorded so far this year. New South Wales and Western Australia are not far behind, with 21 and 18 cases reported respectively.

Healthcare settings such as pharmacies have been increasingly listed as exposure sites as people seek treatment for the highly infectious and virulent disease.

Australian Pharmacist explores the steps pharmacists should take when confronted with this predicament.

Patient contact tracing

When a healthcare setting such as a pharmacy becomes a measles exposure site, it is responsible for contact tracing.

‘We had to inform every patient who was in the [pharmacy] at that time that we were informed that the exposure might have happened,’ Ms Ngo said.

This includes asking patients if they have any symptoms. Early symptoms of measles, before the rash appears, include:

‘We had to inform every patient who was in the [pharmacy] at that time that we were informed that the exposure might have happened.' MINH NGO MPS

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 29352

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-05-14 15:03:20

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-05-14 05:03:20

[post_content] => Dedicated palliative care training for pharmacists is not commonplace. This PSA-developed course aims to change that.

It can be difficult to tell from a prescription that a patient is receiving palliative care, said Tanya Maloney MPS, a community pharmacist in Coffs Harbour, NSW.

[caption id="attachment_29354" align="alignright" width="233"] Tanya Maloney MPS[/caption]

‘What we lack in pharmacy is training on how to approach those difficult conversations in the right way so we can ask them a few questions to determine that,’ she said. ‘We're often a bit nervous about saying the wrong thing.’

Though passionate about palliative care, Ms Maloney and her team have had to learn on the job.

‘We haven’t had any extra training and want to know how we can contribute more.’

This is a common issue through the profession, with a lack in palliative care education tailored specifically to pharmacists, leading to a knowledge gap, said PSA Senior Pharmacist (Consulting and Program Delivery) Megan Tremlett MPS – who has managed a number of palliative care projects through Primary Health Networks and at a state level in recent years.

‘As pharmacists, we don't learn a lot about palliative care in our undergraduate course. And the majority of pharmacists haven't done any extra palliative care education since their university days.’

To address this, PSA launched the ASPIRE Palliative Care Foundation Training Program on 13 May. The free, CPD-accredited course – supported by Palliative Care Australia and funded under the National Palliative Care Grants Program – upskills pharmacists regardless of practice setting.

‘The training program has been created with extensive stakeholder consultation to provide pharmacists with a thorough introduction to palliative care across the eight modules’ Ms Tremlett said.

Rather than training pharmacists to specialise in palliative care, the training program is intended to lift the baseline knowledge of the profession, said Leah Robinson, Project Manager at PSA, who worked on the development of the program with Ms Tremlett.

‘It’s about understanding the different settings and phases of palliative care and at which points pharmacists can provide practical support to help families, patients and healthcare professionals in supporting palliative care.’

A foundational understanding of palliative and end-of-life care across the health workforce is essential to meeting community needs, said Camilla Rowland, CEO of Palliative Care Australia.

‘Supporting people to live, and die well, means building palliative care capability across the entire health system. That includes pharmacists, often among the first healthcare professional patients and carers turn to for advice.’

Tanya Maloney MPS[/caption]

‘What we lack in pharmacy is training on how to approach those difficult conversations in the right way so we can ask them a few questions to determine that,’ she said. ‘We're often a bit nervous about saying the wrong thing.’

Though passionate about palliative care, Ms Maloney and her team have had to learn on the job.

‘We haven’t had any extra training and want to know how we can contribute more.’

This is a common issue through the profession, with a lack in palliative care education tailored specifically to pharmacists, leading to a knowledge gap, said PSA Senior Pharmacist (Consulting and Program Delivery) Megan Tremlett MPS – who has managed a number of palliative care projects through Primary Health Networks and at a state level in recent years.

‘As pharmacists, we don't learn a lot about palliative care in our undergraduate course. And the majority of pharmacists haven't done any extra palliative care education since their university days.’

To address this, PSA launched the ASPIRE Palliative Care Foundation Training Program on 13 May. The free, CPD-accredited course – supported by Palliative Care Australia and funded under the National Palliative Care Grants Program – upskills pharmacists regardless of practice setting.

‘The training program has been created with extensive stakeholder consultation to provide pharmacists with a thorough introduction to palliative care across the eight modules’ Ms Tremlett said.

Rather than training pharmacists to specialise in palliative care, the training program is intended to lift the baseline knowledge of the profession, said Leah Robinson, Project Manager at PSA, who worked on the development of the program with Ms Tremlett.

‘It’s about understanding the different settings and phases of palliative care and at which points pharmacists can provide practical support to help families, patients and healthcare professionals in supporting palliative care.’

A foundational understanding of palliative and end-of-life care across the health workforce is essential to meeting community needs, said Camilla Rowland, CEO of Palliative Care Australia.

‘Supporting people to live, and die well, means building palliative care capability across the entire health system. That includes pharmacists, often among the first healthcare professional patients and carers turn to for advice.’

Learning about symptom management

The ASPIRE training program has a module dedicated to symptoms and the trajectory of people living with life-limiting illness.

Under a subsequent symptom management module, pharmacists can access resources and references for pharmacological management of the symptoms associated with dying that covers:

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 29045

[post_author] => 10221

[post_date] => 2025-05-13 16:45:40

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-05-13 06:45:40

[post_content] => Case scenario

Amra, 80 years old and a regular patient of yours, has been discharged from hospital after an admission for a fall. She presents at the pharmacy with a bag of medicines and hands you a discharge medicines list. She appears to have been initiated on some new medicines in hospital and expresses confusion on which of her pre-hospital medicines to continue. You view her dispense history and My Health Record and notice discrepancies. It is unclear to you or Amra why some medicines have been initiated. She has an appointment with her GP in a couple of days.

Learning objectivesAfter reading this article, pharmacists should be able to:

|

The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC) defines transitions of care as the period when all or part of a person’s healthcare is transferred between care providers or care settings.1

Transitions of care are periods of high risk for medication errors and miscommunication, leading to patient harm. When medicines safety is not prioritised at transitions of care, the risk of adverse events is increased, such as readmission to hospital and adverse drug reactions. A Cochrane review found that more than 50% of patients experience a medication error during transitions of care.2 A systematic review found that following hospital discharge to the community, 53% of adult patients experience at least one medication error, 50% experience one or more unintentional medication discrepancies (a subset of medication errors), and 19% experience one or more adverse drug events.3 A systematic review and meta-analysis found the prevalence of medication-related readmissions and adverse drug reaction-related readmissions in older people were 9% and 6%, respectively, with about one-fifth of these preventable.4

Preventing medication-related harm at transitions of care is a key priority in the World Health Organization’s (WHO) third Global Patient Safety Challenge (Medication Without Harm).5 The ACSQHC’s response to the Challenge, published in 2020, described prioritising medication reconciliation at all transitions of care to reduce the risk of medication errors.6 Its response also recommended the use of My Health Record to engage patients and carers in curation and communication of medication regimen information.

The ACSQHC’s response focused on transitions from hospital, a period known to be particularly high risk, and also recommended standardising the presentation of discharge summaries.6 For people with complex care needs, initiatives to reduce preventable medication-related readmissions were encouraged, such as early post-discharge medication reviews (hospital outreach or primary care led), and cross-sector case conferencing.6 Refinement of risk criteria or indicators was recommended to direct interventions towards patients at the greatest risk of medication-related harm.6

The ACSQHC’s response did not specifically address other known contributors to medication-related harm during transitions of care, such as ensuring timely access to medicines and the tools that are sometimes required to use them, such as interim medication administration charts when discharged to residential care, dose administration aids, and adequate quantities of medicines supply.7,8

The ACSQHC has recently published a set of principles to guide safe and high-quality transitions of care that highlight the need for multidisciplinary collaboration and coordination that relies on shared responsibility and accountability.9 The consistent application of these principles within practice, standards, policy and guidance are fundamental for safe transitions of care and apply to transitions of care wherever healthcare is received including primary, community, acute, subacute, aged and disability care.9

The principles and their enablers are shown in Table 1.

Australia’s priority actions to address medicines safety at transitions of care

Australia’s priority actions to address medicines safety at transitions of careProgress toward Australia’s priority actions to address medicines safety at transitions of care has been mixed.10 Embedding medication reconciliation at admission and discharge from hospital has advanced and is now part of medicines safety standards that hospitals need to meet for accreditation.

My Health Record has improved access to patients’ medication histories; however, patient engagement remains low, and, like all medication records, verification of data with the patient and other sources is required.11,12 Implementation of the Pharmacist Shared Medicines List (a verified medication history that can be uploaded to My Health Record) has been limited. Discharge summaries continue to have deficiencies, including inaccurate medicine lists and inadequate explanations of medicine changes.13 Primary care medicine lists and dose administration aid medicine labels, which are often used by hospital doctors to chart medicines on admission, are also frequently inaccurate.14,15

Australian research highlights concerns about lack of awareness and uptake of post-discharge Home Medicines Reviews (HMRs) and Residential Medication Management Reviews (RMMRs) and the complexity in facilitating timely post-discharge medication reviews.16,17 Hospital outreach pharmacist medication review services and cross-sector multidisciplinary case conferencing are uncommon. There has been progress in developing validated criteria to identify patients at risk of medication-related readmission,18 though more work is needed to ensure generalisability and implementation.10

Progress towards ensuring timely access to medicines following hospital discharge has been mixed.10 Reforms to enable medicines to be supplied by hospitals using the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, and implementation of interim medication administration charts for patients discharged to residential care, have not occurred in all jurisdictions.

In 2020, after decades of advocacy, Commonwealth-funded medication review program rules changed to allow hospital-based medical specialists to refer patients to credentialed pharmacists for collaborative post-discharge medication management reviews. In response, the Society of Hospital Pharmacists (now known as Advanced Pharmacy Australia [AdPha]) published a Hospital Pharmacy Practice Update, Hospital-Initiated Medication Reviews, which detailed information about pathways for patients to have post-discharge HMRs, RMMRs and Hospital Outreach Medication Reviews, as well as flagging MedsChecks as a medication reconciliation pathway.19 Unfortunately, resources were not provided by the Commonwealth or state health departments for promotion, training or implementation support for hospitals to implement hospital-initiated medication reviews, and uptake of these pathways has been low.

An article published in 2022 presented barriers and enablers to hospital-initiated medication reviews, and highlighted the need for a stewardship approach to promote safe and high-quality medication management at transitions of care, with a key focus on facilitating early post-discharge medication reviews (within 10 days).20 The authors have continued to advocate for a hospital-led stewardship approach to address the perennial problem of medicines safety at transitions of care.10,21

The recently published AdPha Standard of Practice for Pharmacy Services Specialising in Transitions of Care describes current best practice for the provision of pharmacy services that specialise in transitions of care, such as hospital outreach pharmacists and community liaison pharmacists, and supports the introduction of transitions of care stewardship programs into existing organisational clinical systems.22

The recently published AdPha Standard of Practice for Pharmacy Services Specialising in Transitions of Care describes current best practice for the provision of pharmacy services that specialise in transitions of care, such as hospital outreach pharmacists and community liaison pharmacists, and supports the introduction of transitions of care stewardship programs into existing organisational clinical systems.22

Stewardship in the context of health care refers to a structured program of strategies and interventions that address challenges within a specific clinical area, and ensure appropriate and efficient use of resources. Medicines stewardship programs focus on improving medicines use in areas where there is a high risk of inappropriate prescribing or adverse outcomes. Examples of successful programs include: antimicrobial, opioid analgesic, anticoagulation and psychotropic stewardship.21

Medicines stewardship programs aim to improve medication management at individual and population levels to ensure consistent, appropriate care. At a population level, this may include developing guidelines and providing standardised processes and templates. At an individual level, it includes delivering tailored person-centred interventions to optimise medication outcomes.

Common elements of successful medicines stewardship programs include multidisciplinary leadership, stakeholder engagement, tailored communication strategies, behavioural changes, implementation science methodologies, and ongoing program monitoring, evaluation and reporting.21 Stewardship programs are often led or administered by a dedicated stewardship officer (usually a pharmacist) or team.21

Applying a stewardship approach to transitions of care may provide opportunities to focus organisational resources, foster multi- or interdisciplinary collaboration, and improve coordinated care when individuals transfer between care providers or settings.

In 2023, the ACSQHC commissioned a rapid literature review and environmental scan examining Australian and international medication management strategies, including stewardship programs, at transitions of care focusing on admission to hospital and discharge to the community or residential care.23,24

The literature review identified that, globally, there are no published studies or existing frameworks that describe a stewardship program specifically addressing medication management at transitions of care.24

Given the evidence from the literature review and environmental scan, the ACSQHC set about developing a Medication Management at Transitions of Care Stewardship Framework (the Framework). The Framework is scheduled for release in the second quarter of 2025.

The Framework is intended to provide healthcare organisations (hospitals) with a systematic approach for implementing coordinated medication management activities and interventions to optimise safe and high-quality transitions of care, with a focus on patients admitted to hospital and discharged to the community or residential aged care. The Framework will provide guidance that can be adapted to local context and the circumstances of individuals transitioning across care settings.

The Framework will be supported by existing national standards and guidelines, including:

The ACSQHC’s principles of safe and high-quality transitions of care9 should also be considered in the local implementation of a medication management at transitions of care stewardship program.

Leveraging digital health

Digital health is a key enabler to achieve interoperable, accurate and timely communication between clinicians in the acute and primary care settings. The Framework will align with the National Digital Health Strategy 2023–202827 and the Strategy Delivery Roadmap.28

Health facilities are encouraged to embed digitally enabled care to strengthen effective interdisciplinary communication and improve safe and high-quality medication management at transitions of care.29

The Framework is designed with a hospital focus, and it is intended that it will be used by hospitals to guide stewardship and coordination in collaboration with primary care practitioners.29

General practice coordination of ongoing medical care prior to and following hospital discharge is vital, as is community pharmacist coordination of medication supply and management. Pharmacists embedded in general practice, onsite aged care pharmacists, and credentialed pharmacists providing HMRs and RMMRs, can also play an important role. However, it is not possible for general practice and primary care pharmacists to coordinate all time-critical aspects of medication management for complex hospital discharges that occur 7 days a week, and sometimes outside of business hours. In the first instance, hospitals need to take responsibility for bridging the gap by29:

The authors encourage all pharmacists to engage with the Framework. It is a world-first document that will drive system improvements so Australians receive high-quality care, and is a pivotal response to the WHO’s third Global Patient Safety Challenge (Medication Without Harm) priority, transitions of care.

Case scenario continuedYou phone the discharging hospital pharmacist (whose name was recorded on the patient’s discharge medicines list) to clarify Amra’s medicine changes and discharge medication management plan. You speak with Amra about your discussion and obtain consent to complete a MedsCheck and chat with her GP about any changes post-discharge. You go through each of her medicines and prepare her an updated medicines list. You also discuss the potential benefits of a Home Medicines Review (HMR) when there has been a hospital admission and medicine changes. You ask if she wishes for you to discuss an HMR referral with her GP which could be actioned at her upcoming GP appointment. She indicates an HMR would be welcome and thanks you for helping her. |

Manya Angley (she/her) BPharm, PhD, FPS, CredPharm (MMR), FAdPha is an Advanced Practice Pharmacist experienced in general practice, disability and aged care.

Debbie Rigby (she/her) BPharm, GradDipClinPharm, FASCP, FPS, FACP, FAICD, FSHP, FANZCAP (GeriMed, Resp) is an Advanced Practice Pharmacist qualified in clinical pharmacy, geriatrics and respiratory medicine.

Rohan Elliott (he/him) BPharm, BPharmSc(Hons), MClinPharm, PhD, FAdPhA, FANZCAP (GeriMed, Research) is an Advanced Practice Pharmacist with experience in hospitals, aged care and transitions of care.

Elizabeth Manias (she/her) RN, BPharm, MPharm, MNStud, PhD, FANZCAP (Transitions of care, Geriatric Medicine)

Manya Angley, Debbie Rigby and Rohan Elliott are co-investigators on a Medical Research Future Fund (MRFF) 2022 transitions of care project. MRFF is funded by the Australian Government. They are also co-authors of a literature review of transitions of care stewardship that was funded by the ACSQHC.

Elizabeth Manias is a member of the Transitions of Care and Primary Care Leadership Committee of Advanced Pharmacy Australia.

[post_title] => Improving medicines safety at transitions of care [post_excerpt] => Transitions of care are periods of high risk for medication errors and miscommunication, leading to patient harm. [post_status] => publish [comment_status] => open [ping_status] => open [post_password] => [post_name] => improving-medicines-safety-at-transitions-of-care [to_ping] => [pinged] => [post_modified] => 2025-05-14 13:04:04 [post_modified_gmt] => 2025-05-14 03:04:04 [post_content_filtered] => [post_parent] => 0 [guid] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/?p=29045 [menu_order] => 0 [post_type] => post [post_mime_type] => [comment_count] => 0 [filter] => raw ) [title_attribute] => Improving medicines safety at transitions of care [title] => Improving medicines safety at transitions of care [href] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/improving-medicines-safety-at-transitions-of-care/ [module_atts:td_module:private] => Array ( ) [td_review:protected] => Array ( [td_post_template] => single_template_4 ) [is_review:protected] => [post_thumb_id:protected] => 29343 [authorType] => )td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 29331

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-05-12 13:28:53

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-05-12 03:28:53

[post_content] => Both Cautionary Advisory Label (CAL) 6 and CAL 13 have been overhauled to sharpen storage advice.

CAL 6 explanatory notes advice in Digital Australian Pharmaceutical Formulary and Handbook (APF) now mentions considerations for room-temperature time windows for refrigerated medicines, while CAL 13’s tightened wording and advice flags truly sensitive formulations – ensuring pharmacists give patients clearer, more precise guidance.

What’s changing?

The familiar ‘Refrigerate, do not freeze’ warning of CAL 6 is not changing, however its explanatory notes have been expanded.

[caption id="attachment_29335" align="aligncenter" width="180"] CAL 6[/caption]

There are many instances whereby refrigeration of temperature sensitive medicines may not be practical, for example travel days, power outages or ‘in-use’ multi-dose containers/devices. The updated explanatory notes advise pharmacists that they should refer to the medicines approved product information (PI) and counsel their patients on how to best store these medicines – covering when their temperature sensitive medicines may safely remain at room temperature (below 25 °C) – if applicable.

[caption id="attachment_29336" align="aligncenter" width="176"]

CAL 6[/caption]

There are many instances whereby refrigeration of temperature sensitive medicines may not be practical, for example travel days, power outages or ‘in-use’ multi-dose containers/devices. The updated explanatory notes advise pharmacists that they should refer to the medicines approved product information (PI) and counsel their patients on how to best store these medicines – covering when their temperature sensitive medicines may safely remain at room temperature (below 25 °C) – if applicable.

[caption id="attachment_29336" align="aligncenter" width="176"] The old CAL 13[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_29337" align="aligncenter" width="189"]

The old CAL 13[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_29337" align="aligncenter" width="189"] The new CAL 13[/caption]

Meanwhile, CAL 13 has been reworded. Previously ‘Do not remove from original packaging until dose required’, the new prompt, ‘Ask your pharmacist about the storage conditions for this medicine,’ applies only to dosage forms and active ingredients truly sensitive to light, moisture or temperature excursions.

This includes orally disintegrating tablets, effervescents, sublingual or buccal lozenges, dispersible granules, wafers and chewables, as well as amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, dabigatran, glyceryl trinitrate, nicorandil, nifedipine, phenothiazines, tamoxifen and sodium valproate.

CAL 13 may also be applied in addition to other CALs relating to storage requirements (e.g. CALs 6, 7a or 7b) when complex storage instructions are applicable, and these other CALs do not adequately cover these.

To support the change to CAL 13, the APF’s Good dispensing practice chapter has been updated with clearer and expanded guidance on providing advice to patients on how to store medicines, including that:

The new CAL 13[/caption]

Meanwhile, CAL 13 has been reworded. Previously ‘Do not remove from original packaging until dose required’, the new prompt, ‘Ask your pharmacist about the storage conditions for this medicine,’ applies only to dosage forms and active ingredients truly sensitive to light, moisture or temperature excursions.

This includes orally disintegrating tablets, effervescents, sublingual or buccal lozenges, dispersible granules, wafers and chewables, as well as amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, dabigatran, glyceryl trinitrate, nicorandil, nifedipine, phenothiazines, tamoxifen and sodium valproate.

CAL 13 may also be applied in addition to other CALs relating to storage requirements (e.g. CALs 6, 7a or 7b) when complex storage instructions are applicable, and these other CALs do not adequately cover these.

To support the change to CAL 13, the APF’s Good dispensing practice chapter has been updated with clearer and expanded guidance on providing advice to patients on how to store medicines, including that:

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 29310

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-05-07 14:26:37

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-05-07 04:26:37

[post_content] => Merging CAL 18 and CAL I removes duplication and confusion, helping patients receive clearer, more actionable dietary advice.

Australian Pharmacist explores what pharmacists and patients need to know.

What’s changing?

Cautionary advisory label (CAL) 18 and CAL I currently provide dietary advice for specific medicines:

[caption id="attachment_29312" align="aligncenter" width="151"] CAL 18[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_29311" align="aligncenter" width="152"]

CAL 18[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_29311" align="aligncenter" width="152"] CAL I[/caption]

CAL I[/caption]

Instead of having two labels that relate to avoiding certain foods and juices (CAL 18 and CAL I), there will now be one – an updated CAL 18.

[caption id="attachment_29313" align="aligncenter" width="189"] Revised CAL 18[/caption]

Revised CAL 18[/caption]

What’s the rationale?

Currently, CAL 18 only warns about grapefruit due to its effect on the bioavailability of certain medicines through the selective inhibition of cytochrome P450 3A4 isoenzymes. But the product information (PI) for new medicines that are substrates for CYP3A4 increasingly mention other fruits (beyond just grapefruit) as interacting with medicines via inhibition of CYP3A4. This includes seville oranges, pomelo, star fruit, bitter melon and pomegranate.

As it stands, the wording of CAL 18 is not broad enough to cover these scenarios.

CAL I is currently used to advise patients about fruits and juices that interact with medicines through mechanisms other than inhibition of CYP3A4.

For example, food and drink interactions with non-selective monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and interactions between medicines and fruit juices through mechanisms other than CYP3A4 inhibition (e.g. fexofenadine, which has been found to interact with orange and apple juice).

However, there have been reports of confusion associated with ‘I’ appearing very similar to ‘1’ in the CAL recommendation table. There are also not many medicines CAL I is relevant to at present, so it therefore has limited applicability.

The revised CAL 18, now reading ‘Certain foods and fruit juices should be avoided while being treated with this medicine’, will now cover:

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 29295

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-05-05 14:47:58

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-05-05 04:47:58

[post_content] => With measles cases climbing across Australia and pharmacies increasingly listed as exposure sites, community pharmacists must be prepared.

Earlier this year, a patient who had just returned from Vietnam walked into Advantage Chesterville Pharmacy in Melbourne with a script for antibiotics.

‘She was wearing a face mask, and when I spoke to her she just said that she had a cough but she wasn't sure what the cough was from,’ said community pharmacist Minh Ngo MPS, who was on duty when the patient came through.

Some time later, the pharmacy received word that the patient was infected with measles.

‘She either informed the hospital or the GP, but we just got a call from the [Victorian] Department of Health to notify us that we were an exposure case,’ she said.

With measles spreading around Australia at an unprecedented rate, this is a position many pharmacists may soon find themselves in.

Victoria is in the midst of its worst measles outbreak in a decade, with 25 cases recorded so far this year. New South Wales and Western Australia are not far behind, with 21 and 18 cases reported respectively.

Healthcare settings such as pharmacies have been increasingly listed as exposure sites as people seek treatment for the highly infectious and virulent disease.

Australian Pharmacist explores the steps pharmacists should take when confronted with this predicament.

Patient contact tracing

When a healthcare setting such as a pharmacy becomes a measles exposure site, it is responsible for contact tracing.

‘We had to inform every patient who was in the [pharmacy] at that time that we were informed that the exposure might have happened,’ Ms Ngo said.

This includes asking patients if they have any symptoms. Early symptoms of measles, before the rash appears, include:

‘We had to inform every patient who was in the [pharmacy] at that time that we were informed that the exposure might have happened.' MINH NGO MPS

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 29352

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-05-14 15:03:20

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-05-14 05:03:20

[post_content] => Dedicated palliative care training for pharmacists is not commonplace. This PSA-developed course aims to change that.

It can be difficult to tell from a prescription that a patient is receiving palliative care, said Tanya Maloney MPS, a community pharmacist in Coffs Harbour, NSW.

[caption id="attachment_29354" align="alignright" width="233"] Tanya Maloney MPS[/caption]

‘What we lack in pharmacy is training on how to approach those difficult conversations in the right way so we can ask them a few questions to determine that,’ she said. ‘We're often a bit nervous about saying the wrong thing.’

Though passionate about palliative care, Ms Maloney and her team have had to learn on the job.

‘We haven’t had any extra training and want to know how we can contribute more.’

This is a common issue through the profession, with a lack in palliative care education tailored specifically to pharmacists, leading to a knowledge gap, said PSA Senior Pharmacist (Consulting and Program Delivery) Megan Tremlett MPS – who has managed a number of palliative care projects through Primary Health Networks and at a state level in recent years.

‘As pharmacists, we don't learn a lot about palliative care in our undergraduate course. And the majority of pharmacists haven't done any extra palliative care education since their university days.’

To address this, PSA launched the ASPIRE Palliative Care Foundation Training Program on 13 May. The free, CPD-accredited course – supported by Palliative Care Australia and funded under the National Palliative Care Grants Program – upskills pharmacists regardless of practice setting.

‘The training program has been created with extensive stakeholder consultation to provide pharmacists with a thorough introduction to palliative care across the eight modules’ Ms Tremlett said.

Rather than training pharmacists to specialise in palliative care, the training program is intended to lift the baseline knowledge of the profession, said Leah Robinson, Project Manager at PSA, who worked on the development of the program with Ms Tremlett.

‘It’s about understanding the different settings and phases of palliative care and at which points pharmacists can provide practical support to help families, patients and healthcare professionals in supporting palliative care.’

A foundational understanding of palliative and end-of-life care across the health workforce is essential to meeting community needs, said Camilla Rowland, CEO of Palliative Care Australia.

‘Supporting people to live, and die well, means building palliative care capability across the entire health system. That includes pharmacists, often among the first healthcare professional patients and carers turn to for advice.’

Tanya Maloney MPS[/caption]

‘What we lack in pharmacy is training on how to approach those difficult conversations in the right way so we can ask them a few questions to determine that,’ she said. ‘We're often a bit nervous about saying the wrong thing.’

Though passionate about palliative care, Ms Maloney and her team have had to learn on the job.

‘We haven’t had any extra training and want to know how we can contribute more.’

This is a common issue through the profession, with a lack in palliative care education tailored specifically to pharmacists, leading to a knowledge gap, said PSA Senior Pharmacist (Consulting and Program Delivery) Megan Tremlett MPS – who has managed a number of palliative care projects through Primary Health Networks and at a state level in recent years.

‘As pharmacists, we don't learn a lot about palliative care in our undergraduate course. And the majority of pharmacists haven't done any extra palliative care education since their university days.’

To address this, PSA launched the ASPIRE Palliative Care Foundation Training Program on 13 May. The free, CPD-accredited course – supported by Palliative Care Australia and funded under the National Palliative Care Grants Program – upskills pharmacists regardless of practice setting.

‘The training program has been created with extensive stakeholder consultation to provide pharmacists with a thorough introduction to palliative care across the eight modules’ Ms Tremlett said.

Rather than training pharmacists to specialise in palliative care, the training program is intended to lift the baseline knowledge of the profession, said Leah Robinson, Project Manager at PSA, who worked on the development of the program with Ms Tremlett.

‘It’s about understanding the different settings and phases of palliative care and at which points pharmacists can provide practical support to help families, patients and healthcare professionals in supporting palliative care.’

A foundational understanding of palliative and end-of-life care across the health workforce is essential to meeting community needs, said Camilla Rowland, CEO of Palliative Care Australia.

‘Supporting people to live, and die well, means building palliative care capability across the entire health system. That includes pharmacists, often among the first healthcare professional patients and carers turn to for advice.’

Learning about symptom management

The ASPIRE training program has a module dedicated to symptoms and the trajectory of people living with life-limiting illness.

Under a subsequent symptom management module, pharmacists can access resources and references for pharmacological management of the symptoms associated with dying that covers:

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 29045

[post_author] => 10221

[post_date] => 2025-05-13 16:45:40

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-05-13 06:45:40

[post_content] => Case scenario

Amra, 80 years old and a regular patient of yours, has been discharged from hospital after an admission for a fall. She presents at the pharmacy with a bag of medicines and hands you a discharge medicines list. She appears to have been initiated on some new medicines in hospital and expresses confusion on which of her pre-hospital medicines to continue. You view her dispense history and My Health Record and notice discrepancies. It is unclear to you or Amra why some medicines have been initiated. She has an appointment with her GP in a couple of days.

Learning objectivesAfter reading this article, pharmacists should be able to:

|

The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC) defines transitions of care as the period when all or part of a person’s healthcare is transferred between care providers or care settings.1

Transitions of care are periods of high risk for medication errors and miscommunication, leading to patient harm. When medicines safety is not prioritised at transitions of care, the risk of adverse events is increased, such as readmission to hospital and adverse drug reactions. A Cochrane review found that more than 50% of patients experience a medication error during transitions of care.2 A systematic review found that following hospital discharge to the community, 53% of adult patients experience at least one medication error, 50% experience one or more unintentional medication discrepancies (a subset of medication errors), and 19% experience one or more adverse drug events.3 A systematic review and meta-analysis found the prevalence of medication-related readmissions and adverse drug reaction-related readmissions in older people were 9% and 6%, respectively, with about one-fifth of these preventable.4

Preventing medication-related harm at transitions of care is a key priority in the World Health Organization’s (WHO) third Global Patient Safety Challenge (Medication Without Harm).5 The ACSQHC’s response to the Challenge, published in 2020, described prioritising medication reconciliation at all transitions of care to reduce the risk of medication errors.6 Its response also recommended the use of My Health Record to engage patients and carers in curation and communication of medication regimen information.

The ACSQHC’s response focused on transitions from hospital, a period known to be particularly high risk, and also recommended standardising the presentation of discharge summaries.6 For people with complex care needs, initiatives to reduce preventable medication-related readmissions were encouraged, such as early post-discharge medication reviews (hospital outreach or primary care led), and cross-sector case conferencing.6 Refinement of risk criteria or indicators was recommended to direct interventions towards patients at the greatest risk of medication-related harm.6

The ACSQHC’s response did not specifically address other known contributors to medication-related harm during transitions of care, such as ensuring timely access to medicines and the tools that are sometimes required to use them, such as interim medication administration charts when discharged to residential care, dose administration aids, and adequate quantities of medicines supply.7,8

The ACSQHC has recently published a set of principles to guide safe and high-quality transitions of care that highlight the need for multidisciplinary collaboration and coordination that relies on shared responsibility and accountability.9 The consistent application of these principles within practice, standards, policy and guidance are fundamental for safe transitions of care and apply to transitions of care wherever healthcare is received including primary, community, acute, subacute, aged and disability care.9

The principles and their enablers are shown in Table 1.

Australia’s priority actions to address medicines safety at transitions of care

Australia’s priority actions to address medicines safety at transitions of careProgress toward Australia’s priority actions to address medicines safety at transitions of care has been mixed.10 Embedding medication reconciliation at admission and discharge from hospital has advanced and is now part of medicines safety standards that hospitals need to meet for accreditation.

My Health Record has improved access to patients’ medication histories; however, patient engagement remains low, and, like all medication records, verification of data with the patient and other sources is required.11,12 Implementation of the Pharmacist Shared Medicines List (a verified medication history that can be uploaded to My Health Record) has been limited. Discharge summaries continue to have deficiencies, including inaccurate medicine lists and inadequate explanations of medicine changes.13 Primary care medicine lists and dose administration aid medicine labels, which are often used by hospital doctors to chart medicines on admission, are also frequently inaccurate.14,15

Australian research highlights concerns about lack of awareness and uptake of post-discharge Home Medicines Reviews (HMRs) and Residential Medication Management Reviews (RMMRs) and the complexity in facilitating timely post-discharge medication reviews.16,17 Hospital outreach pharmacist medication review services and cross-sector multidisciplinary case conferencing are uncommon. There has been progress in developing validated criteria to identify patients at risk of medication-related readmission,18 though more work is needed to ensure generalisability and implementation.10

Progress towards ensuring timely access to medicines following hospital discharge has been mixed.10 Reforms to enable medicines to be supplied by hospitals using the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, and implementation of interim medication administration charts for patients discharged to residential care, have not occurred in all jurisdictions.

In 2020, after decades of advocacy, Commonwealth-funded medication review program rules changed to allow hospital-based medical specialists to refer patients to credentialed pharmacists for collaborative post-discharge medication management reviews. In response, the Society of Hospital Pharmacists (now known as Advanced Pharmacy Australia [AdPha]) published a Hospital Pharmacy Practice Update, Hospital-Initiated Medication Reviews, which detailed information about pathways for patients to have post-discharge HMRs, RMMRs and Hospital Outreach Medication Reviews, as well as flagging MedsChecks as a medication reconciliation pathway.19 Unfortunately, resources were not provided by the Commonwealth or state health departments for promotion, training or implementation support for hospitals to implement hospital-initiated medication reviews, and uptake of these pathways has been low.

An article published in 2022 presented barriers and enablers to hospital-initiated medication reviews, and highlighted the need for a stewardship approach to promote safe and high-quality medication management at transitions of care, with a key focus on facilitating early post-discharge medication reviews (within 10 days).20 The authors have continued to advocate for a hospital-led stewardship approach to address the perennial problem of medicines safety at transitions of care.10,21

The recently published AdPha Standard of Practice for Pharmacy Services Specialising in Transitions of Care describes current best practice for the provision of pharmacy services that specialise in transitions of care, such as hospital outreach pharmacists and community liaison pharmacists, and supports the introduction of transitions of care stewardship programs into existing organisational clinical systems.22

The recently published AdPha Standard of Practice for Pharmacy Services Specialising in Transitions of Care describes current best practice for the provision of pharmacy services that specialise in transitions of care, such as hospital outreach pharmacists and community liaison pharmacists, and supports the introduction of transitions of care stewardship programs into existing organisational clinical systems.22

Stewardship in the context of health care refers to a structured program of strategies and interventions that address challenges within a specific clinical area, and ensure appropriate and efficient use of resources. Medicines stewardship programs focus on improving medicines use in areas where there is a high risk of inappropriate prescribing or adverse outcomes. Examples of successful programs include: antimicrobial, opioid analgesic, anticoagulation and psychotropic stewardship.21

Medicines stewardship programs aim to improve medication management at individual and population levels to ensure consistent, appropriate care. At a population level, this may include developing guidelines and providing standardised processes and templates. At an individual level, it includes delivering tailored person-centred interventions to optimise medication outcomes.

Common elements of successful medicines stewardship programs include multidisciplinary leadership, stakeholder engagement, tailored communication strategies, behavioural changes, implementation science methodologies, and ongoing program monitoring, evaluation and reporting.21 Stewardship programs are often led or administered by a dedicated stewardship officer (usually a pharmacist) or team.21

Applying a stewardship approach to transitions of care may provide opportunities to focus organisational resources, foster multi- or interdisciplinary collaboration, and improve coordinated care when individuals transfer between care providers or settings.

In 2023, the ACSQHC commissioned a rapid literature review and environmental scan examining Australian and international medication management strategies, including stewardship programs, at transitions of care focusing on admission to hospital and discharge to the community or residential care.23,24

The literature review identified that, globally, there are no published studies or existing frameworks that describe a stewardship program specifically addressing medication management at transitions of care.24

Given the evidence from the literature review and environmental scan, the ACSQHC set about developing a Medication Management at Transitions of Care Stewardship Framework (the Framework). The Framework is scheduled for release in the second quarter of 2025.

The Framework is intended to provide healthcare organisations (hospitals) with a systematic approach for implementing coordinated medication management activities and interventions to optimise safe and high-quality transitions of care, with a focus on patients admitted to hospital and discharged to the community or residential aged care. The Framework will provide guidance that can be adapted to local context and the circumstances of individuals transitioning across care settings.

The Framework will be supported by existing national standards and guidelines, including:

The ACSQHC’s principles of safe and high-quality transitions of care9 should also be considered in the local implementation of a medication management at transitions of care stewardship program.

Leveraging digital health