Younger age, substance dependence, mental health histories and higher opioid doses are the risk factors most consistently associated with problematic opioid use, according to one of the largest and most detailed studies to date.1

Key points:

|

The research, published last month, found that the combination of patient characteristics and pre-existing factors was more important than opioid dose alone, which is consistent with previous research.2

With opioid prescribing for chronic non-cancer pain (CNCP) increasing over the past 20 years, accompanied by increased rates of harm, the Pain and Opioid IN Treatment (POINT) study aimed to understand the nature and extent of the problem.1

Researchers interviewed 1,514 patients recruited through 71 Australian community pharmacies across all states and territories over 5 years to 2018 (with a baseline interview and annual follow-ups).

Patients were 18 years or over, had an average age of 58 years and 44% were male. At entry, patients had been prescribed an opioid for a median of 4 years.

Findings at 5 years included:

- 85% remained on a strong opioid

- 9% of the cohort met criteria for ICD-10 opioid dependence

- strongest risk factors contributing to problematic use were: younger age, substance dependence, mental health histories and higher opioid doses.

The findings provide a response to both the concern about high doses causing harm, and the concern that patients with chronic non-cancer pain are being forced to abruptly taper or cease opioids because of a high dose, which is thought to be associated with problematic opioid behaviours. It is an easy risk factor to identify, but sudden cessation can lead to added harms, even death.2

Co-author of the POINT study Associate Professor Suzanne Nielsen MPS, Associate Professor at Monash University and

National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, told Australian Pharmacist that it is vital to respond to the complex needs of patients with chronic pain and mental health conditions in order to reduce harms, and not rely on dose as the key indicator of risk.

The POINT study builds on earlier Monash University research that showed most people overuse opioids to manage symptoms such as pain and mental health conditions.3

What can pharmacists do?

Nicolette Ellis MPS, Advanced Pharmacist Advisor with Queensland Health and senior clinical pharmacist for Beyond Pain, which is a persistent pain video-conferencing program, told AP that many people living with chronic pain feel stigmatised by family, friends and healthcare professionals, including pharmacists.

Ms Ellis reminded pharmacists that the purpose of medicines was to improve function and quality of life, not necessarily reduce pain intensity.

‘The things that bring meaning to our lives are where the conversation should start, not the medicine/opioid,’ she said.

She advised pharmacists to ask individuals how chronic pain was impacting their ability to complete activities of daily living, work and socialising. Objective measurements can be undertaken with tools such as the Pain Inventory Tool or The Pain Enjoyment of Life and General Activity (PEG) scale, as well as goal-setting, which can also help measure the benefit of medicines.

As medicines experts, pharmacists should be able to screen for long-term adverse effects of opioid therapy (i.e. opioid induced endocrinopathy, osteoporosis, opioid induced hyperalgesia, tolerance etc), she said.

‘In my experience, many patients with chronic pain are wanting to reduce the use of medicines but are unsure of how they can function without it,’ Ms Ellis said.

‘This is a really common fear and a reason for resistance. We need to roll with that resistance.’

She also warned of the risk of deprescribing opioids, telling AP that stopping access to opioid medicines without appropriate treatment or ongoing support would result in more harm.

If there is a tapering plan, patients need to agree to it. They need to be reassured that if they find the process difficult, they will be supported by their healthcare team and not abandoned.

In Ms Ellis’s experience, it was possible to taper a very high dose (>800 mg/daily oral morphine equivalent) to 100 mg/day over 2 years.

Ms Ellis also strongly endorsed conversations about the use of naloxone therapy as a very useful harm minimisation strategy. Pharmacists need to discuss its use with patients in a meaningful way, and correct the misconception that it is only for people with substance use disorder or illicit drug use. A useful resource for pharmacists is the Turning Point video.

Pharmacists should consider keeping naloxone nasal spray in stock, as a life-saving and easy-to-use opioid reversal agent in case of unintentional or deliberate overdose. Refer to the PSA guidance document for provision of naloxone.

Similarly, A/Prof Nielsen advised pharmacists to think about clinical outcomes when talking to patients.

‘Ask questions about how well a patient is able to function with their current pain,’ she said.

‘If they are experiencing any problems with their medication [this] might help to identify challenges from the patient’s perspective, and whether their goals are being met.

‘Where patients identify challenges…it can help inform a discussion about whether they want to try different strategies to improve their pain management.’

To reduce opioid-related harm, A/Prof Nielsen said pharmacists could offer staged supply, education around opioid safety and ongoing support with medicine changes.

‘In some cases, the best option might be to taper off opioids, but these decisions should be made in collaboration with the patient and prescriber, following a comprehensive risk-benefit assessment, rather than relying on dose thresholds alone,’ she said.

PSA has developed the cautionary advisory label (CAL) 24 that warns consumers about the risk of opioid overdose and dependence.

PSA has developed the cautionary advisory label (CAL) 24 that warns consumers about the risk of opioid overdose and dependence.

Refer to the Australian Pharmaceutical Formulary and Handbook (APF) 24 for information on opioid conversions, individual drug comparisons, dosing and tapering recommendations and opioid substitution therapy.4

References

- Campbell G, Noghrehchi F, Nielsen S, et al. Risk factors for indicators of opioid-related harms amongst people living with chronic non-cancer pain: Findings from a 5-year prospective cohort study. EClinicalMedicine. 2020. At: www.thelancet.com/journals/eclinm/article/PIIS2589-5370(20)30336-9/fulltext

- Problem opioid behaviours associated with pre-existing risks, not just dosage. 2020. UNSW Newsroom. At: https://newsroom.unsw.edu.au/news/health/problem-opioid-behaviours-associated-pre-existing-risks-not-just-dosage

- Winkle A. These are the reasons people misuse prescription opioids. 2020. Australian Pharmacist. At: www.australianpharmacist.com.au/reasons-people-misuse-prescription-opioids/

- Sansom LN, ed. Australian pharmaceutical formulary and handbook, 24th edn. Canberra: Pharmaceutical Society of Australia; 2020.

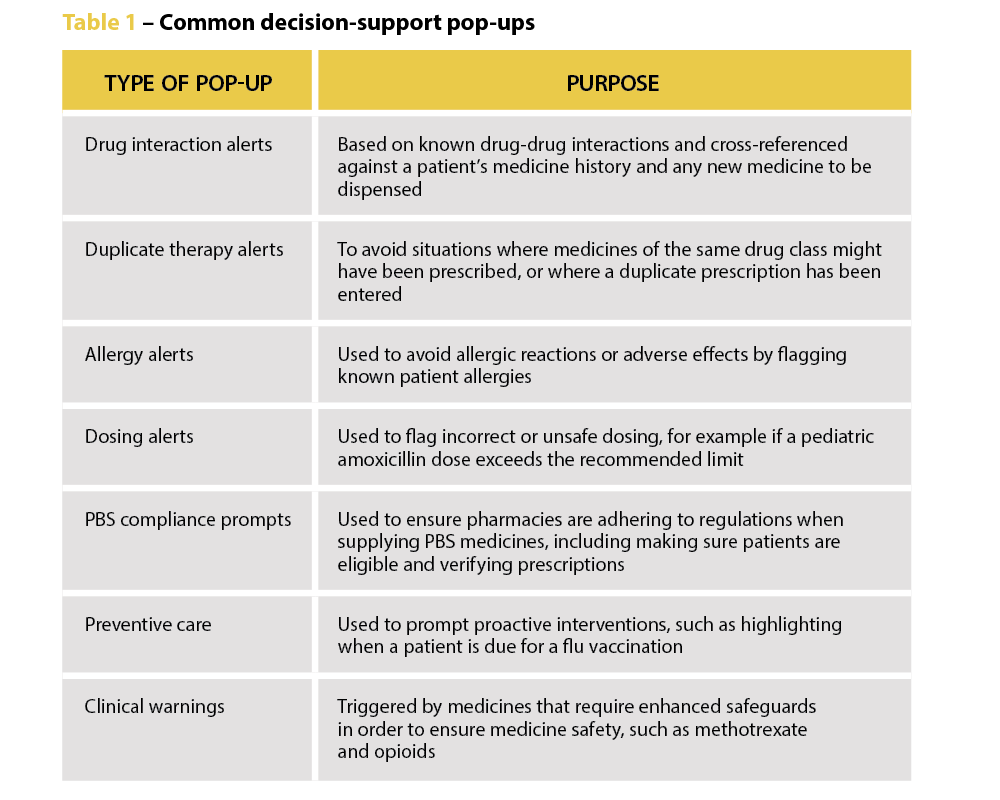

‘We’re increasingly seeing incidents where alert fatigue has been identified as a contributing factor. It’s not that there wasn’t an alert in place, but that it was lost among the other alerts the clinician saw,’ Prof Baysari says.

‘We’re increasingly seeing incidents where alert fatigue has been identified as a contributing factor. It’s not that there wasn’t an alert in place, but that it was lost among the other alerts the clinician saw,’ Prof Baysari says.