For years real-time prescription monitoring (RTPM) has been ‘just around the corner’ in most jurisdictions. Now imminent across Australia, protecting those most at risk will require everyone to use it effectively.

Isaac Reis was just 22 when he died with a cocktail of 10 prescription drugs in his system, all legally prescribed by different doctors over the previous weeks and months.

His father, Paul Reis, said Isaac was so concerned about the amount of drugs he was taking that he asked to be readmitted to a psychiatric hospital for a medicines review.

Isaac was already taking seven medicines when he left the hospital a fortnight before he died, including antidepressants, a benzodiazepine and an opioid. A week before he died he was prescribed two more opioids for back pain, and then a benzodiazepine following

a panic attack the day before his death on August 18, 2019.

Isaac’s death is under investigation by Brisbane Coroner Donald MacKenzie but his family believes he may still be alive if there was a centralised prescription monitoring system to prompt investigation of the combination of drugs.

‘When I found out the medications that were in his system from the autopsy report, Isaac didn’t have a hope in hell of surviving from that mix of medications,’ Paul Reis, told the ABC’s 7.30 in May.

The case has again focused attention on the overdue introduction of a national real-time prescription monitoring system, announced in 2017 by Health Minister Greg Hunt to monitor the prescribing and dispensing of controlled medicines with the aim of reducing their misuse in Australia.

The case has again focused attention on the overdue introduction of a national real-time prescription monitoring system, announced in 2017 by Health Minister Greg Hunt to monitor the prescribing and dispensing of controlled medicines with the aim of reducing their misuse in Australia.

‘Real-time reporting will assist doctors and pharmacists to identify patients who are at risk of harm due to dependency, misuse or abuse of controlled medicines, and patients who are diverting these medicines,’ Mr Hunt said in 2017.

The urgency then – and now – is the increasing rate of unintentional overdoses from prescription drugs like opioids and benzodiazepines, which now outpace deaths from illicit drugs and account for more deaths annually than the national road toll. PSA has long supported a national prescription monitoring system as a medicine safety priority to aid clinical decision-making and provide an opportunity to identify and manage patients misusing specific prescription medications, or those unaware of the risks of polypharmacy.

The PSA’s General Manager Policy and Program Delivery, Chris Campbell, said RTPM would provide insight and awareness to practitioners to make better informed decisions to support patients.

‘It’s not the technology and the information itself that’s the answer, it’s the utilisation of that information and how the pharmacist or prescriber contextualises that information to the patient to treat appropriately,’ he said.

As Dan Schneider, PSA21’s keynote speaker says: ‘Words matter. It’s our responsibility [as pharmacists] to … have sympathy and empathy and compassion and work to solving the problem.

In early 2020 Minister Hunt gave the states and territories until the end of that year to connect their medicines databases to the National Data Exchange that would provide GPs and pharmacists with immediate alerts and information about a patient’s use of drugs of dependency. Upon receiving an alert, the prescriber or dispenser can access a patient’s history of controlled medicines use for the past 12 months. But the RTPM timeline blew out due to COVID-19 priorities for health departments and the need for complex legislative changes in some jurisdictions.

However, the federal Department of Health confirmed to AP that the ‘National Real-Time Prescription Monitoring System’ would finally be operational next year.

‘The Commonwealth Department of Health is working with all jurisdictions to integrate with the national RTPM solution, with all states and territories signed on to use the national RTPM solution by early 2022,’ a department spokesman said.

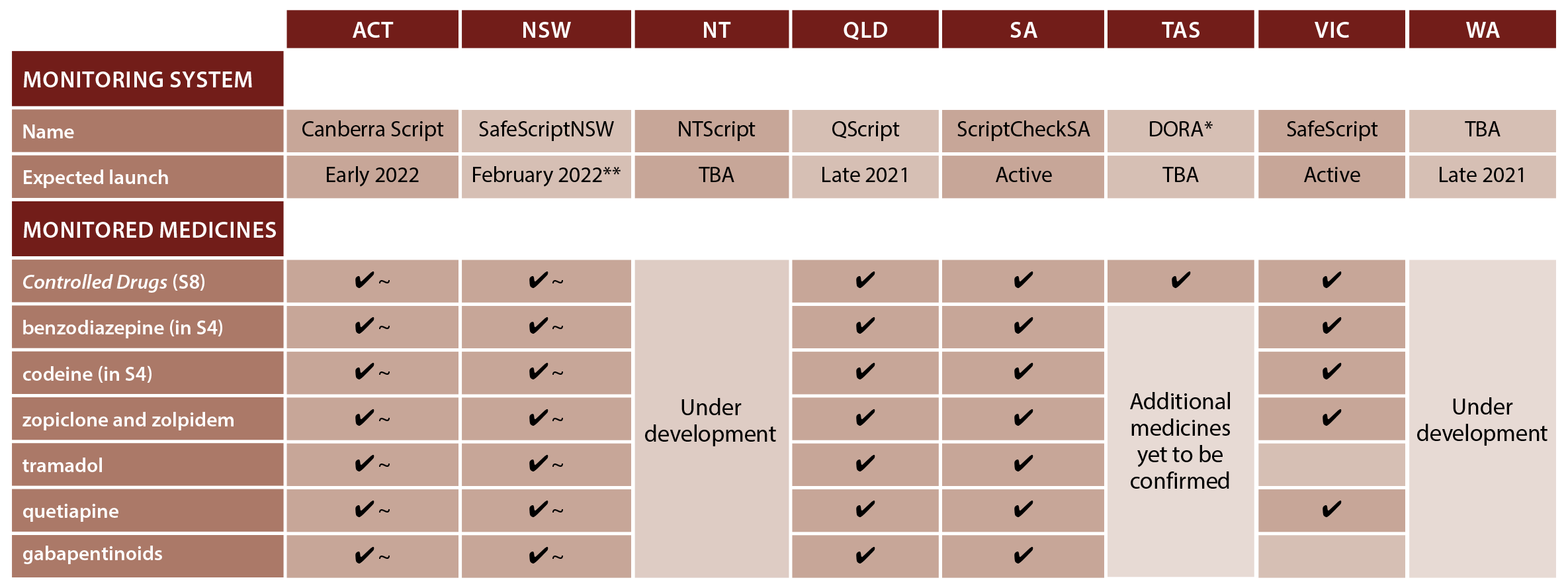

Victoria, South Australia and the ACT have already introduced software for real-time prescription records of Controlled Drugs (Schedule 8) and some Prescription Only Medicines (Schedule 4). Health departments in the remaining states and the Northern Territory confirmed to AP they were on track for implementation later this year, or early in 2022 (see Figure 1).

The impact of RTPM is already visible. In Victoria, where SafeScript started in April 2019, the Victorian Department of Health said a real difference in clinical care had been made with a 25% reduction in the proportion of people taking high-risk doses of opioids in the first 6 months of implementation.

FIGURE 1 – Real-time prescription monitoring: summary of state and territory systems

* DORA continues to operate pending development of system integrating with National Data Exchange and dispense software

** Staged implementation from August 2021 in HNECC. Statewide from February 2022

~ Currently proposed in consultation

The scale of opioid dependency

Alarm bells have been ringing for years about the serious public health issue of opioid-related harm, with Australian coroners calling for a national prescription monitoring system since the 1980s.

Opioids have been identified as a priority substance in the National Drug Strategy 2017–2026 ‘given the significant health, social and economic harms to individuals and the community that can arise from opioid misuse’, a federal Department of Health spokesman said.

‘RTPM alerts will assist prescribers and dispensers to identify patients who are at risk of harm due to dependency or misuse, while still ensuring access for patients who genuinely need these medicines.’

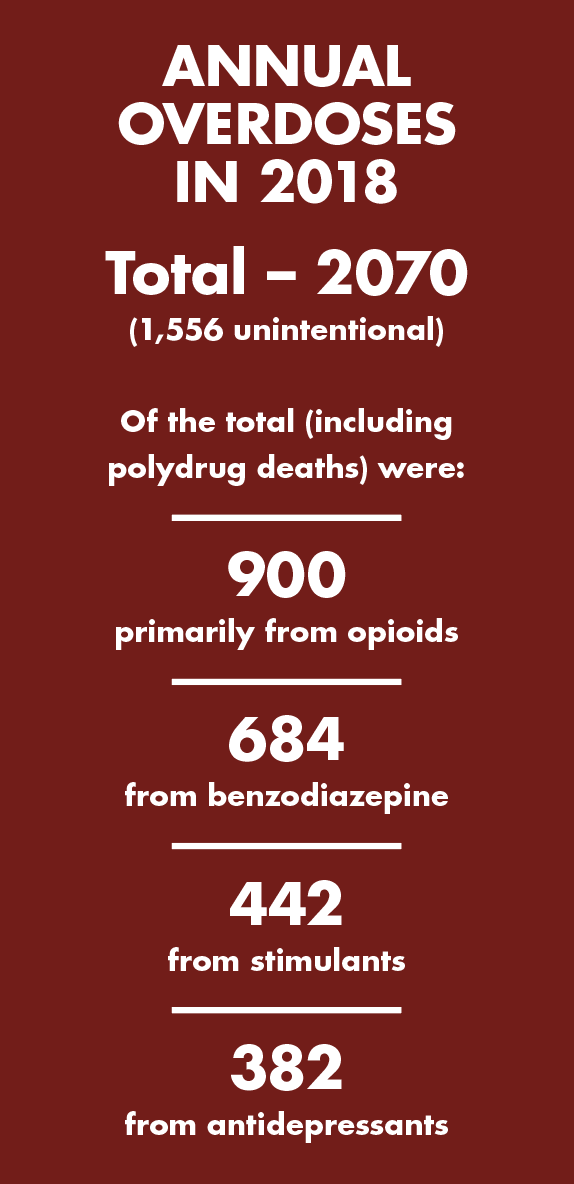

Federal Government data taken on a ‘snapshot day’ in 2020 revealed that more than 53,300 people received pharmacotherapy treatment for opioid dependence at 3,084 dosing points across the country. And the Penington Institute’s Australia’s Annual Overdose Report 2020 found that 2,070 people died in 2018 from drug overdose, and three-quarters of those deaths (1,556) were unintentional.

‘RTPM alerts will assist prescribers and dispensers to identify patients who are at risk of harm due to dependency or misuse, while still ensuring access for patients who genuinely need these medicines.’

Of the total drug overdose deaths, 900 were primarily from opioids, 684 from benzodiazepines, 442 from stimulants and 382 from antidepressants. But the data revealed that poly-drug deaths involving four or more substances had increased markedly in recent years.

‘Unintentional drug-induced deaths are increasing by 3.0% per year, based on trends from the 2001 to 2018 period,’ the report stated. ‘If nothing is done to alter this trend, it will equate to an additional 330 drug-induced deaths by 2023, of which 248 will likely be unintentional.’

And while misconception suggests young people are most susceptible to drug overdose deaths, middle-aged Australians aged 30–59 – and more men than women – have the highest incidence of unintentional drug-induced mortality.

Pharmaceutical opioids were present in more than 70% of opioid-induced deaths and the rate of these deaths with synthetic opioids present has increased significantly over the past decade, the Penington report stated. Natural and semi-synthetic opioids, including codeine, oxycodone and morphine, were the most common prescription opioids present, followed by synthetic opioids.

The doubling of overdose deaths due to codeine from 2000–2009 led the Therapeutic Goods Administration to make codeine products Prescription Only Medicines from February 2018. The TGA also established stricter guidelines around the prescribing of synthetic opioids such as fentanyl, which has been linked to many deaths in the United States.

Is RTPM a silver bullet?

An RTPM system was a ‘very important part of the medicine safety puzzle but it’s only one of the pieces’, PSA’s Chris Campbell says, acknowledging concerns that it could limit access to essential pain care, particularly in palliative care.

His advice is to approach RTPM alerts on issues like patients gaining multiple prescriptions from multiple providers or large dose escalations ‘from a patient care perspective’.

‘The alert is to support the patient in the best way you can. It doesn’t necessarily mean don’t supply; what it means is stop and think about your clinical decision. ‘In some cases,’ he says, ‘if it’s a dose escalation or a medication substitution there’s an opportunity to build rapport with patients and move them towards the care that they need, which might be drug support services.’

It might also be about managing risk through staged supply, coordinating care with a doctor or partial supply until investigated further.

Dan Schneider applauds Australia for doing ‘a much better job’ already in reducing prescription opioid use.

He says it is ahead of the US health insurance version of PBS phone authority as well as the US Pharmacy Monitoring Program (similar to RTPM) which acts as a double-check on US prescribing – ‘particularly if its larger quantities’.

Dan Schneider advises pharmacists not be be ‘apathetic. Don’t feel like you can’t make a difference … the other professions just might not know what we know’.

He told PSA21 of the importance of patience and empathy. ‘These potent drugs now change the brain chemistry. These people don’t have the same inhibitions. We have to realise that in a sense it is a disease that we have to help them through. ‘This can happen to anybody. What if it was your kid?’

References

- Australian Government. Greg Hunt. National approach to prescription drug misuse. 2017. At: www.greghunt.com.au/national-approach-to-prescription-drug-misuse/

- Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. Medicine safety: take care. 2019. At: www.psa.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/PSA-Medicine-Safety-Report.pdf

- Australian Government Department of health. National Drug Strategy 2017–2026. 2017. At: www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/national-drug-strategy-2017-2026

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. National opioid pharmacotherapy statistics. Annual data collection. 2021. At: www.aihw.gov.au/reports/alcohol-other-drug-treatment-services/national-opioid-pharmacotherapy-statistics-2019/contents/introduction

- Penington Institute. Australia’s annual overdose report 2020. 2020. At: www.penington.org.au/publications/2020-overdose-report/

- Australian Government Department of Health. Therapeutic Goods Administration. Codeine information hub. 2018. At: www.tga.gov.au/codeine-info-hub

‘We’re increasingly seeing incidents where alert fatigue has been identified as a contributing factor. It’s not that there wasn’t an alert in place, but that it was lost among the other alerts the clinician saw,’ Prof Baysari says.

‘We’re increasingly seeing incidents where alert fatigue has been identified as a contributing factor. It’s not that there wasn’t an alert in place, but that it was lost among the other alerts the clinician saw,’ Prof Baysari says.

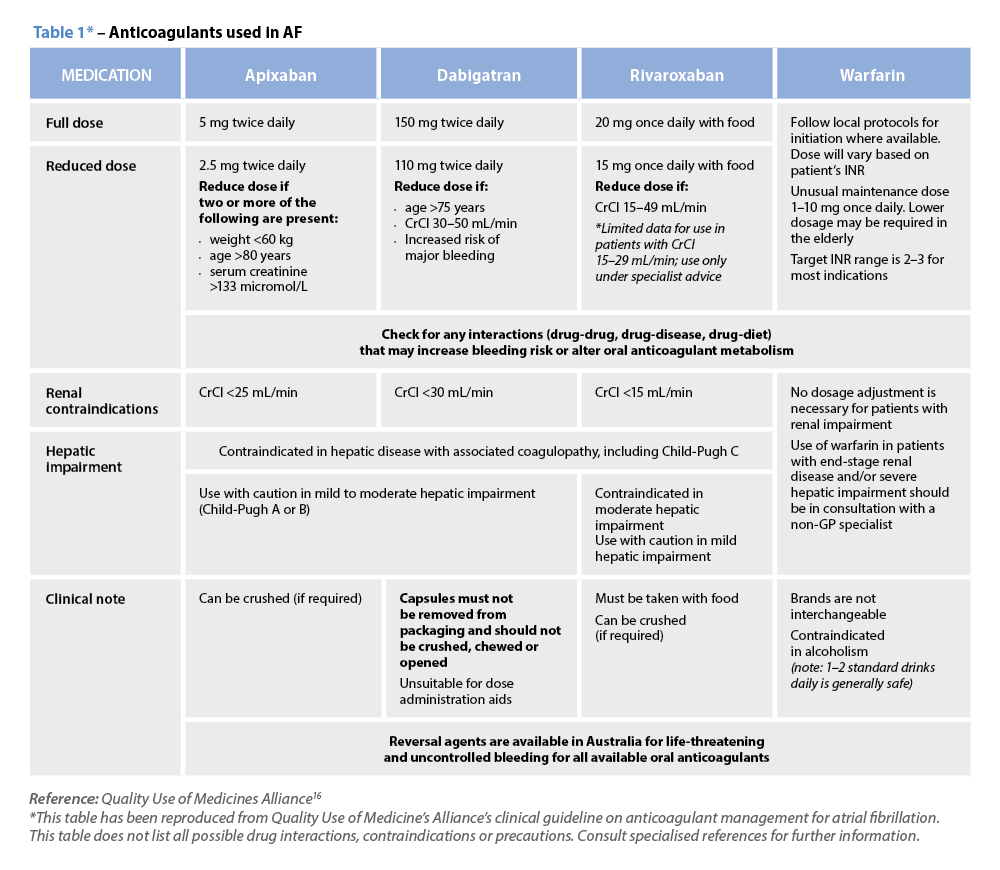

Beyond the arrhythmia, AF often signals broader pathological processes that impair cardiac function and reduce quality of life and life expectancy.5 Many of these conditions are closely linked to social determinants of health, disproportionately affecting populations with socioeconomic disadvantage. Effective AF management requires addressing both the arrhythmia and its underlying contributors.4

Beyond the arrhythmia, AF often signals broader pathological processes that impair cardiac function and reduce quality of life and life expectancy.5 Many of these conditions are closely linked to social determinants of health, disproportionately affecting populations with socioeconomic disadvantage. Effective AF management requires addressing both the arrhythmia and its underlying contributors.4  C – Comorbidity and risk factor management

C – Comorbidity and risk factor management Warfarin

Warfarin