With the launch of a new PSA report, pharmacists in regional and remote areas highlight disadvantages that access to more funding, collaboration and medication management reviews could improve.

Out in the back blocks of far west New South Wales, a man dying of cancer on an isolated rural property forgot that it was mail day. Living in a house in the middle of a 100,000- hectare station, he usually drove 40 kilometres to the nearest village to collect his mail.

On this day he needed some prescriptions dispensed and the Australia Post contractor had already left.

PSA’s 2019 Pharmacist of the Year Peter Crothers FPS, the only pharmacist in Bourke, 250 kms southwest, swung into action.

‘The patient was absolutely desperate about the prospect of going without his medication for 4 or 5 days, and we were concerned, too,’ Mr Crothers says.

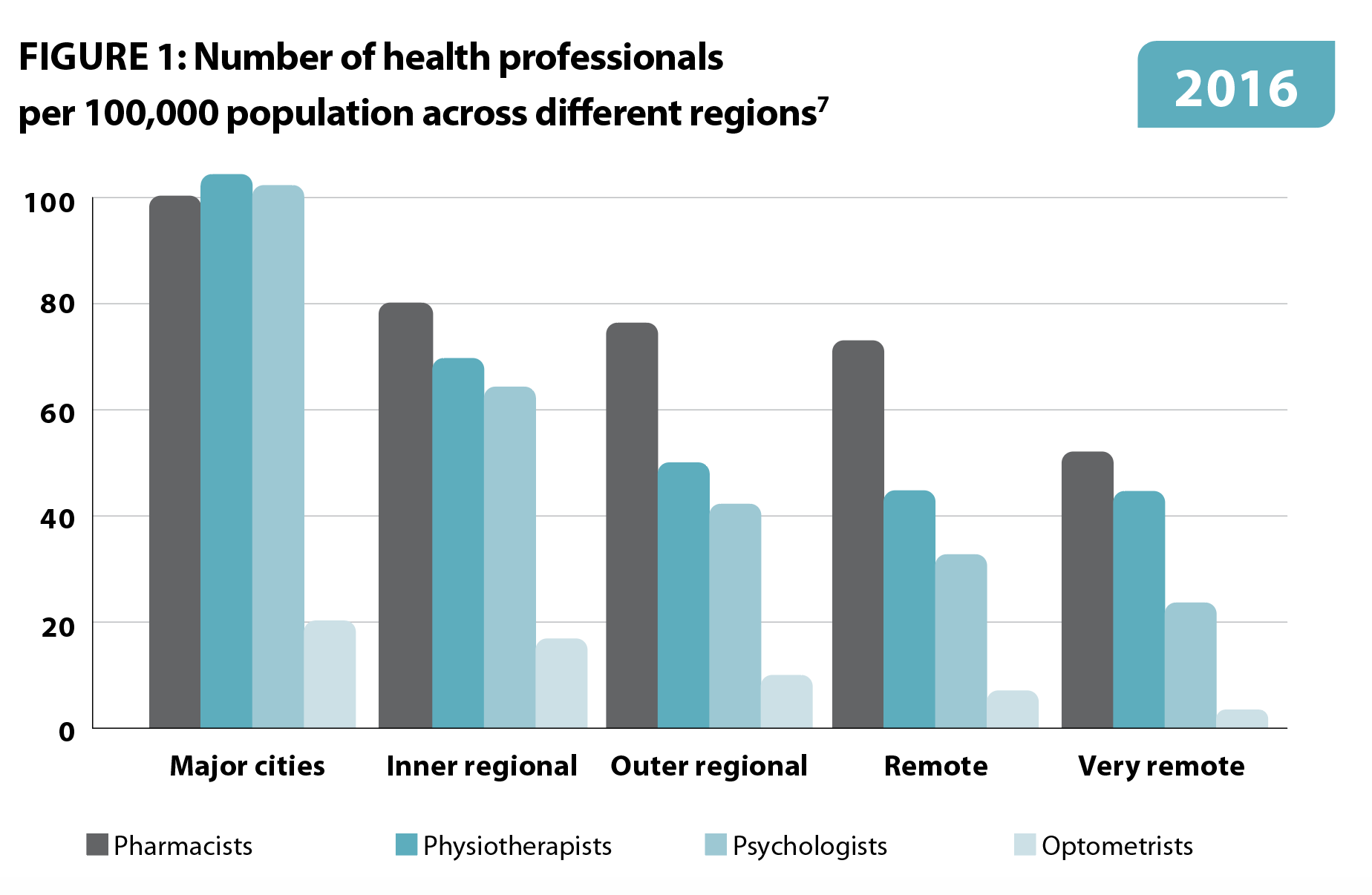

Rural and remote Australia statistics7 million 72,500 $400 million 50% 1.3 million $2.03 billion By 2027, as few as 52 pharmacists per 100,000 people estimated to work in regional and remote areas, comparable to 113 in major cities1 |

Using his deep community connections, Mr Crothers ‘made a few phone calls and we ended up having the medicine delivered to his doorstep by a guy who was going out on a gyrocopter aircraft to do some mustering’.

The pilot was asked to drop the delivery at the local pub, but when he named the place, Mr Crothers said the pilot knew the property had an airstrip and delivered it ‘straight to’ the patient.

‘There are those sorts of things where you clap and jump up and down a bit and think you’ve had a win,’ he says.

But there are many no-win situations for the 7 million Australians in rural and remote – sometimes extremely isolated – areas where healthcare is haphazard or non-existant, or too far away. In these areas there are not enough pharmacists. There are not enough measurements of healthcare delivery and if patients are too much ‘out of sight, out of mind’, even pharmacists, when there is no GP or hospital nearby, cannot help adequately.

For an already under-served, vulnerable population, there is currently an inadequate supply of the health workforce in moderately accessible, remote or very remote areas to provide necessary services.

For an already under-served, vulnerable population, there is currently an inadequate supply of the health workforce in moderately accessible, remote or very remote areas to provide necessary services.

In the latest of its medicine safety reports, Medicine safety: rural and remote care,1 PSA outlines the imbalance between city and rural and remote pharmacist workforces.

It points out the medicine-related harms, including preventable hospital admissions, disease burden, risks to Indigenous Australians, unintentional drug-induced deaths and fluctuating medicine adherence – all cocooned in a lack of empirical data which creates opacity that has resulted in inaction by state and federal governments for years.

‘Rural and remote Australians experience poorer health outcomes, higher rates of hospitalisation and poorer access to primary care,’ the report states.2

Launched last month by NSW Health Minister Brad Hazzard at the Annual Therapeutic Update (ATU) at Manly, the report makes five recommendations (see Box 1) aimed at reducing the extent of medicine-related harm experienced by those living in rural and remote areas.

As PSA National President Associate Professor Chris Freeman says: ‘It should not matter where you live – all Australians are worthy of the best healthcare the country can provide.’

Carli Berrill MPS, co-owner of the Australian mainland’s northern-most pharmacy at Bamaga, on Cape York, Queensland, and at Thursday Island in Torres Strait, and a speaker at the Queensland ATU the week following the NSW ATU, says a ‘huge’ medicine safety issue is patients not taking their medicines ‘because they didn’t know what it was for or no one had ever explained it to them’.

She cites the case of a 60-year-old man from one of the outer islands who missed doses of perindopril, metformin, aspirin and amlodipine for 2 weeks when visiting another island which did not have a local health centre.

‘When I completed my pharmacist support visit I witnessed the effect of not taking his medicines for 2 weeks. He developed osteomyelitis due to uncontrolled diabetes and on his return was lucky to avoid medical evacuation to a hospital,’ Mrs Berrill points out.

‘This patient needed daily antibiotic injections and daily home nurse visits until he was able to get his infection and BGLs under control. His renal function also declined due to this episode.’

BOX 1 – Recommendations for rural and remote care: at a glance1

|

Medicine misadventure

Taren Gill FPS was educated at the University of Sydney and worked for 10 years in the NSW regional town of Orange, population 40,000, where she was given the PSA Early Career Pharmacist of the Year award in 2014. Today she co-owns a pharmacy in rural Maryborough, Victoria, with just 7,000 people. Other professionals commute in from Ballarat, and doctors don’t see patients on weekends.

Maryborough is within the shire that has the highest cancer incidence in Victoria, the highest cardiovascular disease rate and wasn’t far behind Ararat as the ‘most overweight shire’. Throw in domestic violence and mental health issues and ‘there’s enough sick people’ for pharmacists and general practitioners alike, she says, of the good relationship she has with local GPs.

She cites the case of a patient taking sertraline 50 milligrams, with its out-of-stock issues, as well as different brands sold at different pharmacies. The patient didn’t realise that the brand from one pharmacy in one town was the same as the different brand from another pharmacy elsewhere. He then added it to his ‘daily regime – doubling and tripling the dose, and having medicine misadventure as a result’.

‘Another issue,’ Ms Gill says, ‘is the idea that city hospitals think they can discharge people at any time and assume that the access and resources when they hit their towns is going to be like a city, where you can go into the pharmacy at 8 pm, or that the pharmacies are resourced and open to create a WebsterPak on discharge or have weird and wonderful items in stock.’

Indigenous Australians

The rate of hospitalisations for Indigenous Australians for chronic conditions, for instance diabetes, is on average, more than three times that for non-Indigenous people. They have a burden of disease 2.3 times higher than non-Indigenous Australians and reduced life expectancy.

Compliance is a huge issue and can’t be fixed alone by telehealth medication reviews, says Carli Berrill.

‘It needs a pharmacist on the ground as much as possible at the clinic to ensure that all possible clients are seen and culturally appropriate medication education and reviews have been completed with follow-up and reiteration of information as needed.’

And caps on MedsChecks and Home Medicines Reviews (HMRs) for remote pharmacies should be ‘uncapped’, she says.

Pharmacy service integration with Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations (ACCHOs) is ‘uncommon’, according to the report.

Ellen Jones MPS, who works for the Gidgee Healing ACCHO in Mt Isa, Queensland, says a ‘key challenge’ in sourcing more pharmacists in such roles is ‘recognition and remuneration’.

‘We are significantly under-represented in the Medicare Benefits Schedule, and other funding arrangements make funding for positions scarce. The strict rules around the HMR program sometimes make it logistically challenging to execute, as well as not always being the most culturally appropriate way to deliver pharmacist care.’

She says engagement with ACCHOs is integral to establishing community and organisational needs around identifying patients at risk of medicine misadventure.

In Bourke, Indigenous Australians make up about 38% of the population. Peter Crothers says assisting Aboriginal people accounts for two-thirds of his workload.

‘Aboriginal people have some particular issues around medication safety,’ he says. ‘One factor is low personal security. You meet a lot of people who don’t have a wallet or a handbag, for example, because they don’t feel confident in keeping those things safe. That can create issues around the possibility of other people getting access to people’s medications, medications getting lost – those sorts of things.’

Invisible work

The co-chairman of Rural Pharmacy Network Australia Fred Hellqvist MPS has had nearly a decade of first-hand experience of the invisible work done by remote pharmacists that is also unpaid.

His Dover Pharmacy is the most southern on the Tasmanian mainland, and the only one in his postcode.

As the only active pharmacist in his outer regional location, there is a ‘huge workload’ connecting with state healthcare providers, the local fire services during bushfires and ‘the police to make sure you can get your medications in’. And then, there have been COVID-19 issues on top.

‘We are significantly under-represented in the Medicare Benefits Scheme, and other funding arrangements make funding for positions [in ACCHOs] scarce.’ Ellen Jones MPS

‘Because of our socioeconomics, which also drive the high chronic disease rates in our area, we have to solve problems then and there. A lot of people are poorer, so they may have a car but they can’t afford to drive their car back and forth. Or they may not have a car and rely on others for transport,’ he says.

‘When they do come to the pharmacy, we have to, as much as possible, solve [the problem]. That could mean speaking with GPs, specialists or other healthcare professionals on the patient’s behalf.

And, ‘it’s about solving it adequately’, so the patient can continue treatments, or a healthcare plan until the next GP or specialist appointment.

‘You can imagine the time that this sometimes takes, which is currently unremunerated. It’s not captured. It’s not monitored.’

For governments, ‘the priority should be to improve remuneration for services, as well as workforce incentives for the already existing network’, Mr Hellqvist says.

Health professional access

Pharmacies in towns where general practitioners are already scarce in relation to patient numbers ‘can exacerbate health disparities’, the PSA report states.

‘In 2017, the full-time service equivalent (FTE) per 100,000 population was 65, 75 and 85 FTE per 100,000 in very remote, remote and outer regional areas, respectively, compared to 110 FTE for major cities and inner regional areas.’

One report cited a prediction that in 2027–28 ‘there would be 80 and 52 pharmacists per 100,000 people in regional and remote areas, respectively, compared to 113 pharmacists per 100,000 people in major cities.3

Reduced doctor and telehealth services in the bush has meant an 80-year-old patient of Karen Carter FPS, who lives outside Gunnedah, NSW, missed her annual HMR this year, as well as last year. As the patient’s condition worsened, Karen’s pharmacy supplied a dose administration aid (DAA), but when the patient lost it, the pharmacy needed to make a special delivery with another DAA.

Another patient, aged 78, could not get another prescription for tramadol for his pain, so stopped it, Ms Carter recalls.

‘His mood plummeted. He saw a doctor who prescribed an antidepressant.’

It was later sorted out when the patient spoke to Mrs Carter’s pharmacist, who then ‘spoke to the doctor who restarted tramadol and not antidepressants’.

Burden of disease

Outside major cities, there is a higher prevalence of health risk factors, including obesity, smoking, non-nutritional diets, sedentary lifestyles and alcohol abuse.

According to the PSA report, the burden of disease increases with remoteness ‘for coronary heart disease, chronic kidney disease, COPD, lung cancer, stroke, suicide, self-harm and type 2 diabetes’.

In addition, outside capital cities, Australians pay more for goods and services but receive 18% less in weekly household income. The burden for remote-living Australians has been estimated at 1.4 times that of those living in cities, and 2.3 times for Indigenous Australians.4

But due to a lack of empirical data, the contribution of medicine-related harm to the burden of disease is not possible to strictly determine. It is likely, however, that such a burden implies increased need for medicines and thus increased risk of harm.

Potentially avoidable deaths occur in very remote regions at a rate 2.5 times that of major cities,5 while proportionally higher potentially preventable hospitalisations (PPH) and presentations to Emergency Departments in rural and remote areas compared to cities, likely due to medicine-related harm,’ the report states.

Workforce

Shortages of healthcare professionals, which includes pharmacists, in rural and remote areas is well known and a major contributor to poorer health outcomes.

Challenges include higher workloads than metropolitan counterparts, which can be exacerbated by short staffing, difficulty accessing locum relief, more duties and working as a sole practitioner.

On top, as the report states, the cost of accommodation and travel for pharmacists already under financial hardship and difficulties taking leave without replacement staff then interfere with ongoing training and professional development conference attendances.

Taren Gill can’t recruit pharmacists to her town. ‘If I don’t grow my own,’ she says, referring to her three interns, ‘I can’t get any‘. And even they will leave, eventually.

Suboptimal medicine use and harm

Some of the factors which contribute to medicine-related harm include polypharmacy – ≥5 medicines (including ‘hyper-polypharmacy’ – ≥10 or more medicines and ‘extreme hyper-polypharmacy – ≥15 or more medicines), medicine adherence, mental ill-health, transitions of care and overuse of opioids.

About half of people with chronic disease don’t take their medicines correctly, or at all, sometimes.6

As Mr Hellqvist points out, pharmacists ‘fill a lot of gaps. We have to advise on diabetes care, because we don’t have diabetes educators on a regular basis.There’s a lot of mental health, where we have to follow people over time, because we’ve gained their trust over the years. People trust us [pharmacists] with more things regarding their health.’

FIGURE 2 – Extent of medicine use in rural and remote Australia

|

Australian |

Rural and |

|

|

People taking a prescribed medicine every day |

> 9 million |

2.61 million |

|

People taking two or more prescribed medicines in a week |

8 million |

2.32 million |

|

People taking over-the-counter medicines daily |

> 2 million |

0.58 million |

|

People taking a complementary medicine daily |

> 7 million |

2.03 million |

Reference: NPS MedicineWise8

The way forward

With complex and multifactorial causes of medicine safety problems, a specific focus on the rural health workforce is needed, the report states.

‘Without a specific focus on the rural health workforce in Australia we will see little improvement in complex and chronic disease management, and we risk failure in delivering on the objectives of Australia’s 2019 Long Term National Health Plan and unique National Medicines Policy.’

It is imperative that integrated healthcare emphasises greater collaboration between services with a ‘new way of providing primary care’.

‘Rural and remote pharmacists in Australia have an opportunity to significantly address the breadth of disadvantage afflicting many people living in rural and remote Australia. Innovative models of care, available to rural and remote practitioners, should be adopted and implemented as a matter of urgency,’ the report states.

As Fred Hellqvist says, with more funding via workforce incentives, more pharmacists can be attracted to rural areas – and the invisible work may at last be paid.

References

- www.psa.org.au/advocacy/working-for-our-profession/medicine-safety/medicine-safety-rural-and-remote-care/

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Rural and remote health: snapshot. Canberra: AIHW; 2020.

- Gardiner FW, Gale L, Ransom A et al. Looking ahead: Responding to the health needs of country Australians in 2028 – the centenary year of the RFDS. Canberra: The Royal Flying Doctor Service; 2018.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australian burden of disease study: impact and causes of illness and death in Australia 2015. Australian Burden of Disease series no. 19. Cat. no. BOD 22. Canberra: AIHW; 2019.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s health 2018. Australia’s health series no. 16. AUS 221. Canberra: AIHW; 2018.

- Brown MT, Bussell JK. Medication adherence: WHO cares? Mayo Clin Proc 2011;86(4):304–14.

- Obamiro KO, Tesfaye WH, Barnet T. Strategies to increase the pharmacist workforce in rural and remote Australia: a scoping review. Rural Remote Health 2020;20(4):5741.

- NPS MedicineWise. With millions taking multiple medicines, Australians are reminded to Be MedicineWise. 20 Aug 2018. At: www.nps.org.au/media/with-millions-taking-multiple-medicines-australians-are-reminded-to-be-medicine-wise

‘We’re increasingly seeing incidents where alert fatigue has been identified as a contributing factor. It’s not that there wasn’t an alert in place, but that it was lost among the other alerts the clinician saw,’ Prof Baysari says.

‘We’re increasingly seeing incidents where alert fatigue has been identified as a contributing factor. It’s not that there wasn’t an alert in place, but that it was lost among the other alerts the clinician saw,’ Prof Baysari says.